Understanding how to reuse material

The availability of works under an open license has increased dramatically since the Creative Commons licenses were launched in 2002. As of today, there are around 2 billion works released under a Creative Commons license[1], and many more with other types of licenses (such as the GFDL)[2].

The reason why the Creative Commons licenses became so widespread it’s because they offer considerable flexibility to creators and users. Creative Commons licenses include six licenses and two public domain tools. Creative Commons are standardized tools. Each of the licenses and tools have three layers of legal language, user language, and machine readable code. This is what makes CC licenses such a powerful tool. They have been translated to many languages, so users can understand in their own language what they can and can’t do with a work that is licensed under a CC license.

However, it is not always easy to understand how to use works under a CC license, or how to license your own work. Additionally, CC licenses only cover the aspects of a work that are related to copyright. Any other right, such as personality or privacy rights, are not covered by the CC licenses. This means you need to examine the work you’re planning to incorporate in your storytelling or narrative to decide if you can use it.

To decide if you incorporate a particular work into your narrative, you need to first understand some important aspects of the licenses and your intended use.

Understanding your use

Before deciding where to look for works that you can use, you need to define what is your intended use of those works.

The two main things that you have to consider are:

- Is your use of the works an adaptation or a combination (also called “collection”)?

- Do you plan to give the work a commercial use?

For deciding whether your use is an adaptation or a combination, you have to ask yourself the following questions: Are you planning to remix it into a larger work, or are you planning to use it “as it is”, to illustrate a point or indicate an element? For example, are you planning to use a set of icons in a larger infographic material about the importance of regulating hate speech on social media, or are you planning to remix public domain works to make a collage poster that depicts an abstract concept of gender equality?

This is an important distinction between adaptation and combination. Adaptation is when you take a set of existing works to create a new, distinguishable work. When you adapt a work, it’s hard to distinguish when each of the works start and when they end (i.e., a collage).

Combining works (or making a collection of works) is when you take a set of existing works and combine them or arrange them in a way that still produces a new work, but where each work being combined remains its separate, own work (i.e., the icons in an infographic).

Additionally, you need to consider how you plan to use and license your work afterwards. Are you planning to sell the resulting work or use it for a for-profit purpose? How do you want to license your own work?

Creative Commons offers an extensive review of the licensing considerations that you need to consider in their FAQ section “Combining and adapting CC material”.

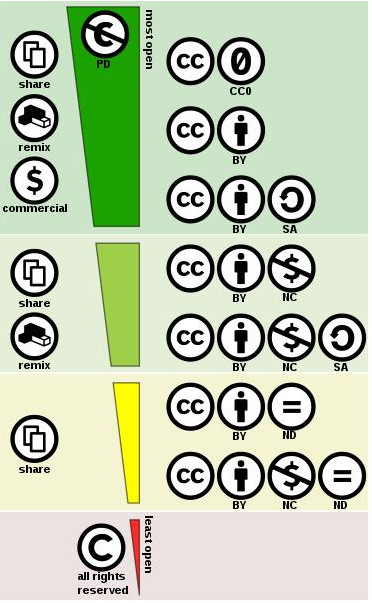

However, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed with all the different charts and considerations on how you’re supposed to incorporate works with the non-commercial, share-alike or non-derivatives clause. The easiest way to avoid all this complexity is to limit your search to materials that are made freely available with little to no restrictions. This means that you will only search for works that are preferably under a CC BY, a CC BY SA or a CC0.

Pro Tip: To avoid complexity, search for materials that you can freely reuse with little to no restrictions. This means searching for materials under the CC BY and CC BY-SA license or the CC0 tool. You can use search filters and specific media repositories that will give you only these results when searching.

If you want to use any work under the remaining licenses (CC BY-NC, CC BY-SA-NC, CC BY-ND, CC BY-NC-ND) you will have to ask yourself:

- Is the resulting work an adaptation or a combination of works?

- Do I want to make a commercial use of the resulting work?

If you want to use a material that has a CC BY-NC-ND or a CC BY-ND, you need to be aware that you can’t make distributions of any adaptations you make to the work. That means that you will only be able to incorporate works under those licenses “as they are”, without any modifications.

This graphic of the “spectrum of CC licenses” shows that the licenses placed in the dark green area of the graphic are the “most free” licenses. The works released under the licenses placed in the dark green area are also the ones that are easier to incorporate in any new work.

“Creative Commons License Spectrum” by Shaddim (CC BY 4.0)

In the next sections we will explore how to search for works that are under the licenses placed in the dark green area. But in a nutshell, different search filters and specific media repositories will give you materials licensed in these ways.

Other considerations when using and reusing CC licensed material

The CC licenses don’t cover other rights different from copyright. Any image, sound, moving image, or other representation may have other legal or ethical rights. Legal rights are rights that are enforceable while ethical considerations might not be legally enforceable, but you need to consider when respectfully using the material. These rights include:

- Trademarks: an openly licensed resource might contain representations of trademarks (for example, a photo that shows the iconic logo of a fast food chain);

- Publicity rights: certain living people depicted in openly licensed photos might be covered by publicity rights (i.e., a photo of a singer or performer);

- Privacy rights: depictions of living people might also be subject to privacy rights.

- Ethical considerations: all the other considerations that emerge but are not coded in law and/or related to copyright law in particular.

These all apply even when the resource might be openly licensed.

Trademarks

As a general principle, it’s a good idea to avoid using depictions or representations of trademarks or their logos. However, you might be able to use works that represent or depict a trademark if you are going to critique the trademark or if you want to illustrate a point (for example, a slide that shows the top 10 companies causing environmental harm in your country could be illustrated with their logos).

You might also want to avoid potential connections between a narrative and a trademark. For example, if you are doing storytelling on the obesity epidemic and its impact in the developing world, you want to avoid including a representation of the iconic logo of a soda company. While there might be a connection between sodas and obesity, you want to avoid being that specific. You can use something less specific (for example, a photo of a line of sodas in an aisle in a supermarket).

Publicity rights

Avoid using photos of famous people, unless the story that you are building is about the person or refers to the person somehow. The protection of publicity rights might not be as strong when related to politicians. Publicity rights vary widely: make sure to know your local laws before representing famous people.

Privacy rights

Privacy rights can be complicated legally and should be treated alongside ethical considerations. Some jurisdictions have different considerations for privacy rights. However, in many jurisdictions around the world: if a person is in a public space, then their expectations of privacy should be lower. What does that mean? In short, it means that if, for example, you decide to participate in a manifestation of some type (a public performance, protest, etc), then you should anticipate that others could be taking pictures of you without your consent. Your participation in the public space is, in a way, a form of consent.

This is highly controversial and problematic. As an example, let’s take a look at the story of the Pulitzer prize winning photos of 2015 of the Ferguson protests in the United States, taken by the white photographer Robert Cohen. The photo depicts a black man, Edward Crawford, grabbing a gas canister and throwing it back at the police with an American flag in flames. The black man was later harrased by the police (arguably because of the photos that placed him at the place of the protest) and died under circumstances that still remain unclear. This brings very interesting questions about how protests should be respectfully depicted, including but not limited to how this might put in danger other people's lives.

You need to be extremely careful in which contexts you might reuse depictions of living people. As a general principle, reusing any depiction of living people could be a misuse, in the sense that you are taking a depiction of a person and using it in a context and for a purpose that was not the context or purpose that the person being depicted anticipated. However, there are uses that are more acceptable than others. For these ethical considerations, context is everything.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations might or might not be rooted in legal systems. “Ethical considerations” refer mainly to respectfully using representations of people and cultures. Some of these considerations are very heavily related to context, so always bear in mind what your audience might be for your storytelling.

Pro Tip: If you are not sure whether your use or reuse is legal, ethical or respectful, then search for another resource that makes you feel more confident.

As a general principle, use the following criteria to decide whether the your intended use is appropriate:

- Did the person give consent to be depicted in the way in which she or he is being depicted? If you suspect that the media, photo or representation was taken without the consent of the person, then avoid using it in your work.

- Is the representation respectful of the situation in which the person might be situated in? For example, if you want to depict “poverty in Latin America”, avoid using images or representations that might bring stigma over the people or situation being depicted. Avoid also using tokenizing representations.

Does the representation of the person or situation put the person’s life at risk in any way?

Avoid using photos that might put someone’s life or safety at risk, even if the license allows for free reuse. Consider questions like: does the photo show someone doing something illegal? Does the photo show someone easily identifiable while protesting power? If the photos you find are in a community with ethical norms look for a way to report it: for example, on Wikimedia Commons consider also asking for deletion .

Does the use that you intend to do of the work show the person or situation being depicted in a positive, affirmative action?

There are manifestations that take place as part of affirmative actions. For example, Pride Parades in contexts where LGBTIQ+ rights are fully granted3 are a good example of such affirmative actions. This is an example of a photo taken at a Pride Parade in Berlin in 2015, which was later re-used in a set of postcards to ask for the implementation of the Marrakesh Treaty for people with print disabilities. These are examples of affirmative actions.

Does the person that took the photo belong to the cultural or geographical context?

An important aspect to consider here is also who might have produced the media you intend to use. While sometimes it’s impossible to know this for sure, there are different levels of confidence. Writer Sasha Alyson in his blog “Karma colonialism” points out how different aid agencies normally don’t hire local talent for their photo-shoots, converting these depictions into another form of colonialism and othering. There are other resources that are openly licensed that have been produced by local people, for example, the contests organized by Wiki Loves Africa.

Does your intended use include any identifiable traits of the person?

Depending on what story you are telling, you might want to avoid using works that show identifiable traits of the person. For example, if you are writing a report about working environments in Indonesia, you can use openly licensed photos, but you might want to avoid showing people whose face or traits are recognizable and that were taken in a different context from the project. Readers of your story might interpret those people as “the people impacted by the program” rather than as anonymous people. Instead, you might want to consider showing more abstract photos of working environments, or only select certain portions of the body (for example, hands on a computer).

Does the person belong to a minority group?

There are certain groups that have been historically depicted without their consent and with a colonialist perspective. That’s frequently the case of indigenous people, artifacts and customs. Some of these representations are part of archival materials stewarded by cultural heritage institutions that make them available because copyright expired. That doesn’t mean that these representations are less problematic. For example, many libraries and archives in North America have published 19th century photos of Native American traditions not meant to be shared. Reusing these images extends this injury. Ask yourself whether the representation is appropriate.

Understand how your reuse fits into your narrative

Once you have finished putting together your storytelling or narrative, you need to make sure that the overall story does not accidentally misrepresent the people or topic in a poor way. For example, you might have selected certain types of representations that build bias into your story.

When unsure, search for other resources

If you are confident your use is ethical, then search for another resource that makes you feel more confident. You might spend a bit more time on the search, but it’s better to feel safe about your reuse.

As a final consideration, also avoid works that depict scripts or languages that you don’t understand. If you don’t know the language, you might be using offensive or out of context terms without realizing. An exception to this rule is when these scripts are being displayed in public and properly contextualized, for example, the “Monument to the Reader” in Yerevan, Armenia.

What happens if I use a material offered under a CC license and the author decides to remove or change the CC license?

CC licenses are irrevocable. This means that if someone decides to change their mind about the license they are using, you can still use it under the terms that it was offered to you. However, sometimes this could potentially make someone wary of using a work under a CC license, because how might you prove that the material was offered to you under a CC license?

A good idea is that whenever you are using and reusing material offered to you under a CC license, you do one (or both) of the following:

- Upload the photo to Wikimedia Commons: using the Upload Wizard, you can add the source where you find the material, alongside with the tutorial. The Upload Wizard offers a step by step guide.

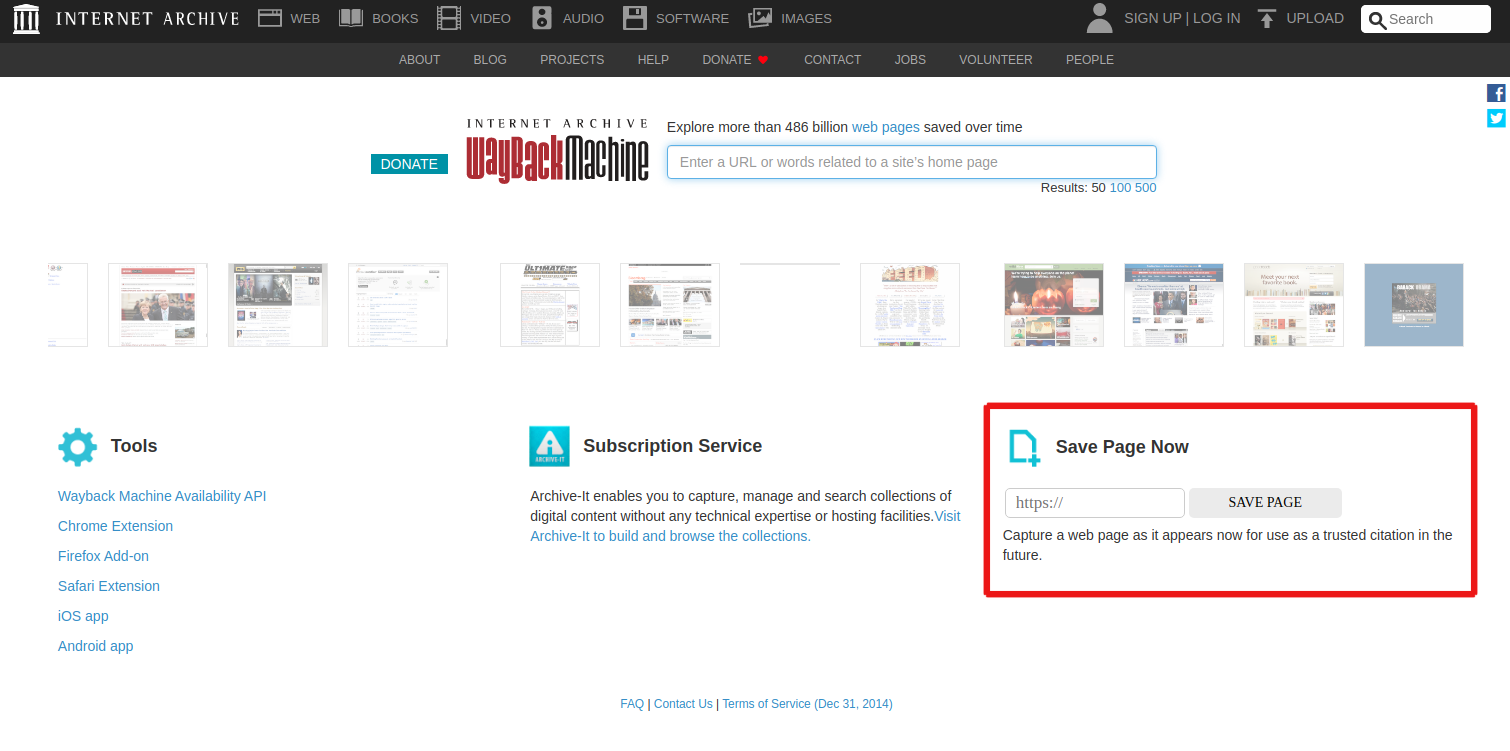

Save the link on the Wayback Machine: the Wayback Machine is an archiving service of website pages offered by Internet Archive. You can go to the Wayback Machine website and use the “Save page Now” function:

If you paste the URL in that box, it will create a “snapshot” of the page, with a unique URL. You could potentially also use that URL as an alternative source when using the “TASL approach” (more on that in the next section).

Lastly, an important point is that you might wish to respect the desires of the author that decides to change the license to their content, avoiding reusing that content in the future, even when you might have the snapshot of the website.

[1]1 Creative Commons annual report (2019), available here: https://creativecommons.org/2020/11/05/creative-commons-2019-annual-report/[2]2 This tutorial will only work with CC-licensed material to avoid introducing more complexity.[3]3 Avoid using photos of LGBTIQ+ parades or manifestations in contexts where their rights are at risk or their lives might be in danger.