Section 1: Digital identifiablity and content production

Expand our understanding of anonymity and how it is never a permanent state of non-identifiability.

Introduction

Oftentimes, we will immediately think of being anonymous when we do not want others to recognize us in the telling of our stories. There is no doubt that anonymity has played a particularly huge role in making it easier to tell difficult stories, especially when these stories speak of atrocious human rights violations and there is a continuous need to protect the storyteller or to reduce the sense of vulnerability and targeted persecution of a marginalized individual or community.

Learning objectives

This section is aimed to expand our understanding of anonymity and how it is never a permanent state of non-identifiability. “Anonymity”, in practice, generally means to be nameless and faceless. However, you can be recognizable despite being nameless and faceless and this section explains how this can be possible. The section asks that we shift our focus on security and our safety in telling our stories or first person narratives by better understanding digital identifiability. By the end of this section, the participants will:

- Gain an increased understanding of the link between anonymity and safety.

- Be able to identify the difference between anonymity and non-identifiability.

- Gain an increased understanding of the importance of establishing trustworthiness and credibility in storytelling, especially if it is in relation to discrimination, stigma and violence.

- Understand the link between metadata and safety in digital storytelling.

Creating anonymity

Creating anonymity can be done in many ways. For example, in Nepal, domestic violence survivors have resorted to speaking behind curtains in telling their stories. In most situations, vulnerable storytellers will agree to tell their stories in videos/film as long as their faces are not shown or blurred and/or their voices distorted (see see Section 2: General Safety Considerations in Content Production and Choosing Technology for Storytelling and Sharing Your Stories). However, many human rights activists and storytellers strongly discourage the blurring faces or distorting of voices; the reasons why link to establishing trustworthiness and credibility of the storyteller.

Victims/survivors of human rights violations who have told stories anonymously include, among others, domestic violence survivors, those who have been trafficked, and those who face marginalization, stigmatization and religious persecution such as lesbians, gays, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) persons, people living with HIV and AIDS and women who have alleged sexual harassment against perpetrators who continue to hold power over them, likely because of employment and financial dependence of other forms.

Anonymity, specifically its adjective "anonymous", is derived from the Greek word word anonymia, meaning "without a name" or "namelessness". So anonymity usually means in real terms to be nameless and faceless. However, you as the digital storyteller can be nameless and faceless in various ways.

For example, in everyday circumstances, and to her family, friends, and authorities, this is Susan Chan.

Image Source: Adapted from from https://freesvg.org/group-of-people-vector-image.

IMPORTANT Note: Photographs or images of real people are not used because of the inability to get direct consent, and at this point, a real image of a person does not necessarily better facilitate understanding.

|

Creating Anonymity |

|||

SUSAN |

ANONYMOUS |

||

| Susan (a generic or common first name, without |

Use an avatar-type icon but with a pseudonym: “Pootie Pie” | Instead of a name or pseudonym, just refer to her as “anonymous” (without a face) | A mere silhouette |

Image Sources: Adapted from from https://freesvg.org/group-of-people-vector-image

Some people have argued that namelessness, though technically correct, does not capture what is more centrally at stake in contexts that require anonymity. This is because anonymity is not necessarily equivalent to non-identifiability, and the risk of identifiability in fact increases in digital spaces.

The important idea here is that a person be non-identifiable, unreachable, or not trackable. Anonymity is seen as a technique, or a way of realising certain other values, such as privacy, or liberty. However, anonymity does not guarantee a permanent state of non-identifiability because its effectiveness is affected by space and time, or context.

In short, it is impossible to be anonymous in every single space and at every single time. So this module is to help us shift our mind sets to linking security and safety with non-identifiability rather than merely anonymity in the telling of difficult stories, and stories of human rights violations.

Storytelling and non-identifiability

There is no doubt that in many cases, anonymity is the main technique used to secure non-identifiability. From witnessing crimes and whistle-blowing to claiming human rights from violent perpetrators and perpetrators who continue to hold oppressive power over us. So in telling difficult stories, we often have to think about, quoting Foucault, to which power are we speaking our truths. Foucault was a French philosopher, whose theories examined the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. It is precisely because our difficult stories disrupt the status quo and challenge the power and privilege of some, it is important to also consider when anonymity is considered illegal in your country and under what circumstances your identity as a storyteller may have to be revealed because of the law.

This module focuses on digital storytelling and not recounting stories as victims/survivors, witnesses or whistle-blowers. The two are quite different because recounting a story as a victim/survivor, witness or as a whistle-blower requires verification of facts (by authorities and other third parties such as human rights defenders) and the establishment of the chronology of events.

The table below provides some key differences between between storytelling and telling telling stories as victims/survivors, witnesses or whistleblowers of human rights violations/crimes, that is, telling stories for evidence-gathering.

|

The Differences between Digital Storytelling and Telling Stories as Victims/Survivors, Witnesses or Whistleblowers of Human Rights Violations/Crimes |

|

|

Telling Stories for Evidence-Gathering |

Digital Storytelling |

|

Identity has to be identifiable, at least, to selected authorities/persons and human rights defenders. |

Identity need not be identifiable |

|

Content needs to be verified by human rights organisations and/or authorities for facts/details, chronology of events, and accuracy |

Content need not be verified for facts/details, chronology of events and accuracy |

|

Content should just state what happened, and use actual visuals of persons involved (if possible), voices, places, etc. |

Content can be creatively delivered, using storyboards, and other storytelling techniques. |

Identities and non-identifiability

In using “stand-ins” to represent yourself, like avatar icons, you must always check to what extent it is identifiable with you. For example:

- A photograph of your favourite café in a specific location will render you more identifiable compared to a place you have never been to.

- Using a pseudonym that friends and others know that it is something you are fond of using or have used before, makes you identifiable. The earlier example of Susan Chan shows that she uses “Pootie Pie” as a pseudonym, but if people who know her know Susan Chan loves “Calvin and Hobbes” and in particular, Hobbes, the use of “Pootie Pie”, even though a pseudonym makes her likely identifiable.

- Using an avatar that looks like you makes you identifiable. The earlier example of Susan Chan shows that her avatar icon looks like her, short black her, similar shape of the head, etc.

- Using a photograph of your best friend or friends makes you identifiable.

- Using your initials and birthdate definitely makes you identifiable!

What you use to represent yourself as the storyteller tells a lot about you except for something generic like “anonymous” or “pseudonym”.

Some storytellers do think that their names are so generic in their social contexts that it would be difficult for people to know if it is really them, especially on social media where only handles are used or the image is non-identifiable. If you have such a name in your locality or country, do remember that while it may be a little difficult, it still means that your identity would be one of those suspected for those who have met you, know you and come across your story online. You are also identifiable by the content that you have been posting online which may refer to your regular activities, or a specific event that others know you attended.

Your identity, however, is not merely limited to your name and your face. It is your skin colour, the shape of your hands, your favourite nail polish, your favourite shoes, your worn out sandals, the way you dress, your bag, your toes, your fingers, your nose, your mouth, your eyes, your ears, the side of your face, the way you wear your hair, the kind of haircut you have, your bedroom, your study, the front of your house, the back of your house, the place you work, the road you live on, your family, your children, your partner, your friends, your neighbours, your office colleagues, any cause you are associated with, the way you walk, the way you sit, the way you stand, and the way you talk. All of these can also be easily identified with you if you have been active on social media and have been posting a lot about your life, your activities, where you go, what you do, and who you hang out with.

Identifiability and narratives

The way you talk and tell your story tells a lot about you. The way you string words together, your writing style, your favourite words and phrases, and what you usually say to express shock, anger, surprise, all tell on you.

Voice

Some of you may already be thinking “my voice is certainly identifiable with me”, but storytellers have also pointed out how the voice alone is not necessarily identifiable. This is because voices can sound similar to one another, unless your voice is a popular personality’s voice, a radio personality’s voice, a popular singer’s voice, a broadcaster journalist’s voice or a politician’s voice. Unless you have spoken in public many times, or are already a known and public/popular personality, what makes your voice identifiable is more about what you say and how you say it.

Past recounting of your story

Finally, your story will be identifiable if you have shared it before (whole or in part) or if others intimately know you and the specific experience you are speaking of. For example, an ex-husband who was violent towards you would know who you are if you speak of a particular experience, if you reference your mother, father or children. If you talk of a dress you were wearing, the kitchen where it happened, and so on.

Using storytelling techniques

What can help make you less identifiable is in telling your story in response to someone who has a similar story, someone you are unlikely to tell a story with, and someone whom your family and friends have not met. This means placing your story against another story, almost like a backdrop to your story or you may want to weave together two stories in such a way, that they reflect each other in parallel. These are tricks of storytelling and narrative development, and you may want to explore how to shape a narrative through creative storytelling techniques. Such as using a different starting point as your story, or speaking ambiguously in relation to your identity and yet tell a story that carries your truth.

REMINDER: Human rights defenders who want to use your story for witnessing or part of their evidence against a human rights crime will certainly not encourage you to use storytelling techniques. For such stories, you will likely need to talk about the specific incidence in chronological order with as much facts and clarity as possible.

Non-identifiability and credibility

One of the main reasons why storytellers should not ever blur their own faces is because you want to establish your trustworthiness with your audiences. Increasingly, blurring of faces and distortion of voices is often associated with being a criminal. Not showing your face does not mean you cannot show other parts of yourself (but do check the extent of identifiability) or use things to represent you (like a flower, a rainbow, a movement, a place, shoes, a river, etc.).

In the human rights sector, when storytellers speak of human rights violations and abuses, it is often anchored on the credibility of the human rights or intermediary organisations that publishes and distributes these stories, and ultimately uses them for policy advocacy and/or to pursue justice for the victims. For first person narratives, however, or what people generally refer to as personal storytelling, there are two key aspects that lend credibility:

- The clarity of your voice. The more muffled your voice sounds, the less likely you will come off as a trustworthy storyteller.

- The resonance people have with your story lends believability and credibility to the story content, which in turn allows people to give you the benefit of the doubt despite you not being identifiable as the storyteller.

These aspects are particularly important for individuals, groups and communities who are discriminated against or considered deviant such as people living with HIV and AIDS, sex workers, migrant workers, refugees and LGBTIQ persons.

CRITICAL ONGOING DEBATES: Some of the more recent debates around anonymity and human rights involve the use of encryption and the defense of our basic right to digital anonymity. This is because some governments, if not all governments, are keen on establishing a back door to encryption so that they can see what content you are browsing (such as a the use of HTTPS to help secure your browsing activities over the internet) and if you are a potential threat to national security. However, an interesting distinction is made between cultivating an opinion by doing the necessary reading and/or research, and expressing that opinion with conviction. These debates have serious implications for human rights storytelling because lived realities are fact, but perception of the experience itself, the negative impact, the perceived reasons for such violence and abuse (other than the actual acts of violence and abuse), can be said to be the storytellers attempt to try to make sense of the discrimination and violence, and should not also be penalized in any way for such expression.

Manipulating images to make them less identifiable

How-to steps

Manipulating images to make them less identifiable

What makes an image identifiable? The faces in it. Details that identify a location – common landmarks, street names, unique features.

Content producers need to determine before they start capturing images and footage if they want to make their content less identifiable as they take the photograph or the footage, or if they will manipulate the images and the footage for anonymity non-identifiability after they have captured and stored them.

The most safest option is for digital stories to to obscure images and footage as they are being captured. This means, even if someone gets access to the raw footage or images, the people in it are not going to be identifiable, and there will not be an original image or footage stored somewhere online or offline that they may get access to.

There are some techniques that a storyteller can use to make the people in a photo or a video footage anonymous:

- Don´t capture people´s faces but rather capture their hands or their feet as they are being interviewed.

- Use the silhouette effect – to place a strong light source behind the subject as described here:

- Keep identifiable location markers (street names, identifiable buildings) out of focus in taking a photo or a capturing footage

- Use filters available on Instastories, Tik-tok and Snapchat to make videos less identifiable.

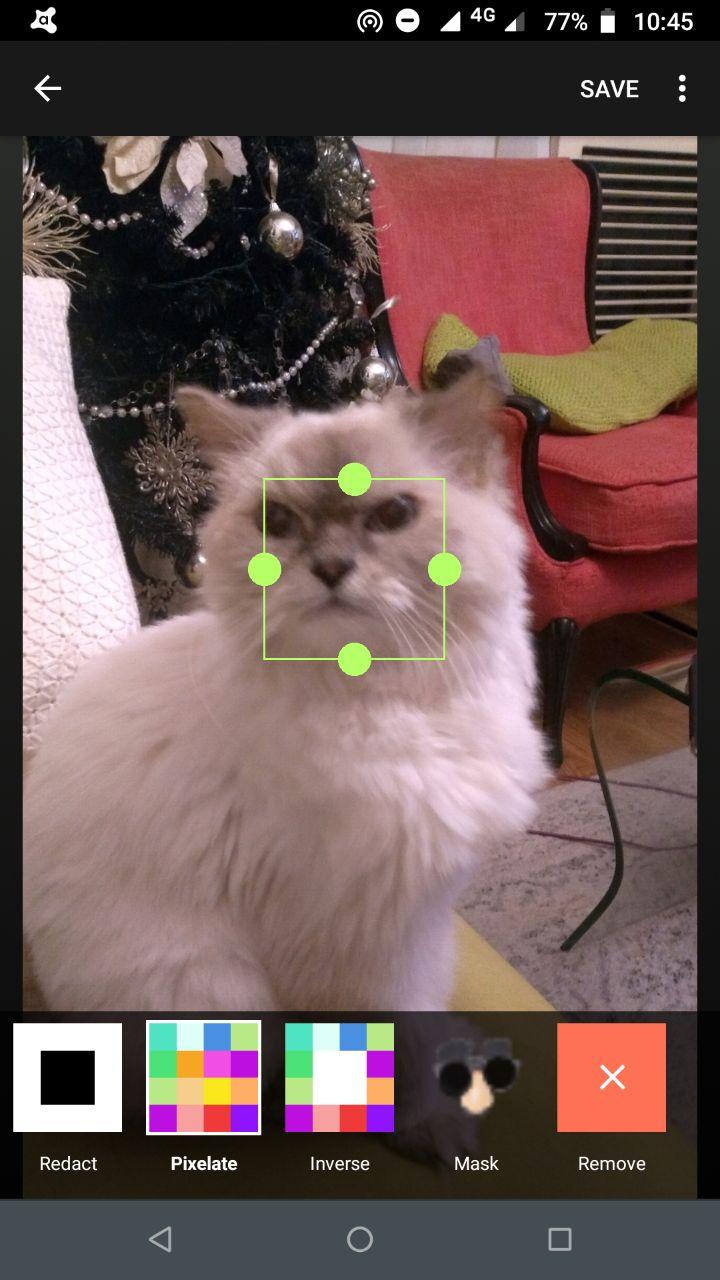

- ObscuraCam

Take a photo or open the image the you want to edit in in ObscuraCam. Then click on the image.

What you will see is a movable and resizable box that will let you control what you want to obscure.

You will get the following options for obscuring the photo:

Pixelate: this will pixelate whatever is captured within the box

Invert: This will pixelate whatever is outside the box

Redact: This will delete whatever is in the box

Mask: This will add a mask on the image in the box

Then save the image.

ObscuraCam is especially useful if the storyteller opts to take anonymous or less identifiable photos from the start.

Note: If the storyteller opts to anonymise, meaning to make images less or non-identifiable after they are captured, they will have to take extra steps in storing their raw images and video footage more safely.

Using GIMP to create less or non-identifiable photos

Open the image to be manipulated. Analyse what you want to anonymise or make less or non-identifiable. Do you want to anonymises identifiable make faces less or non-identifiable? Or do you want to make certain elements in the photo that will make the locations or surroundings less or non- location identifiable?

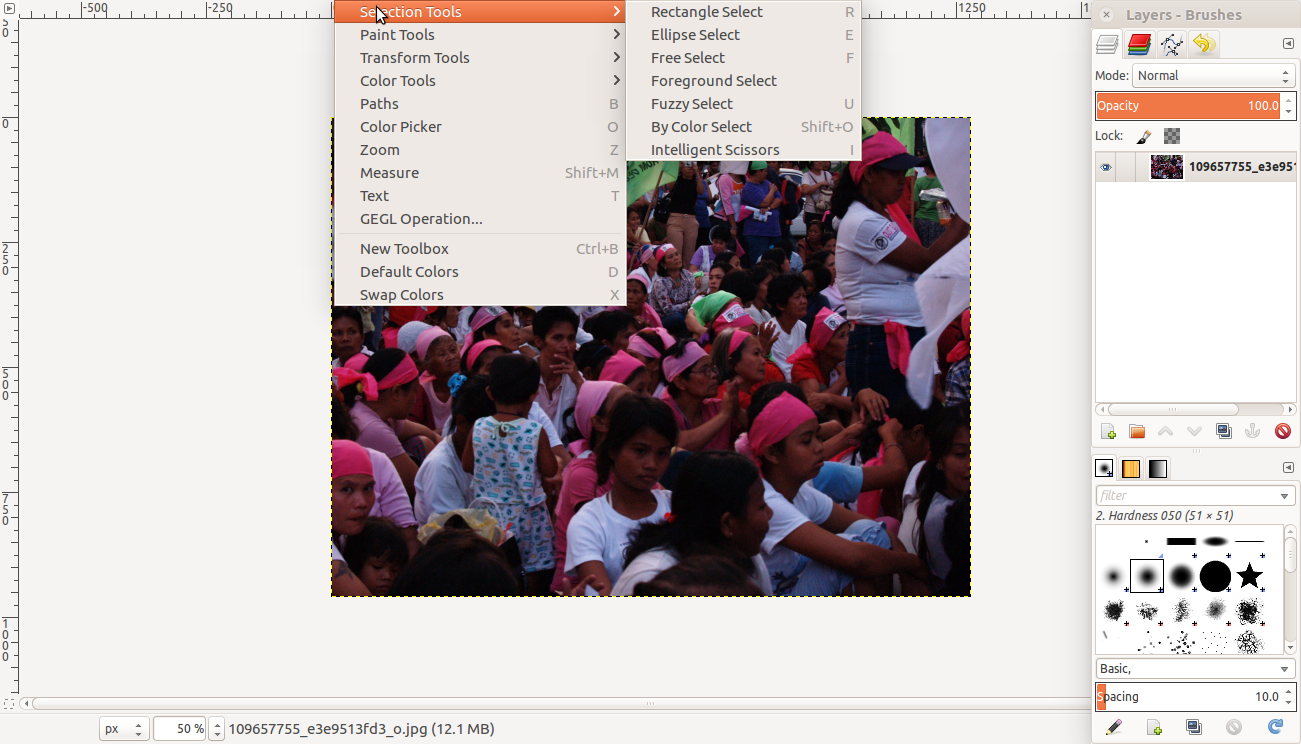

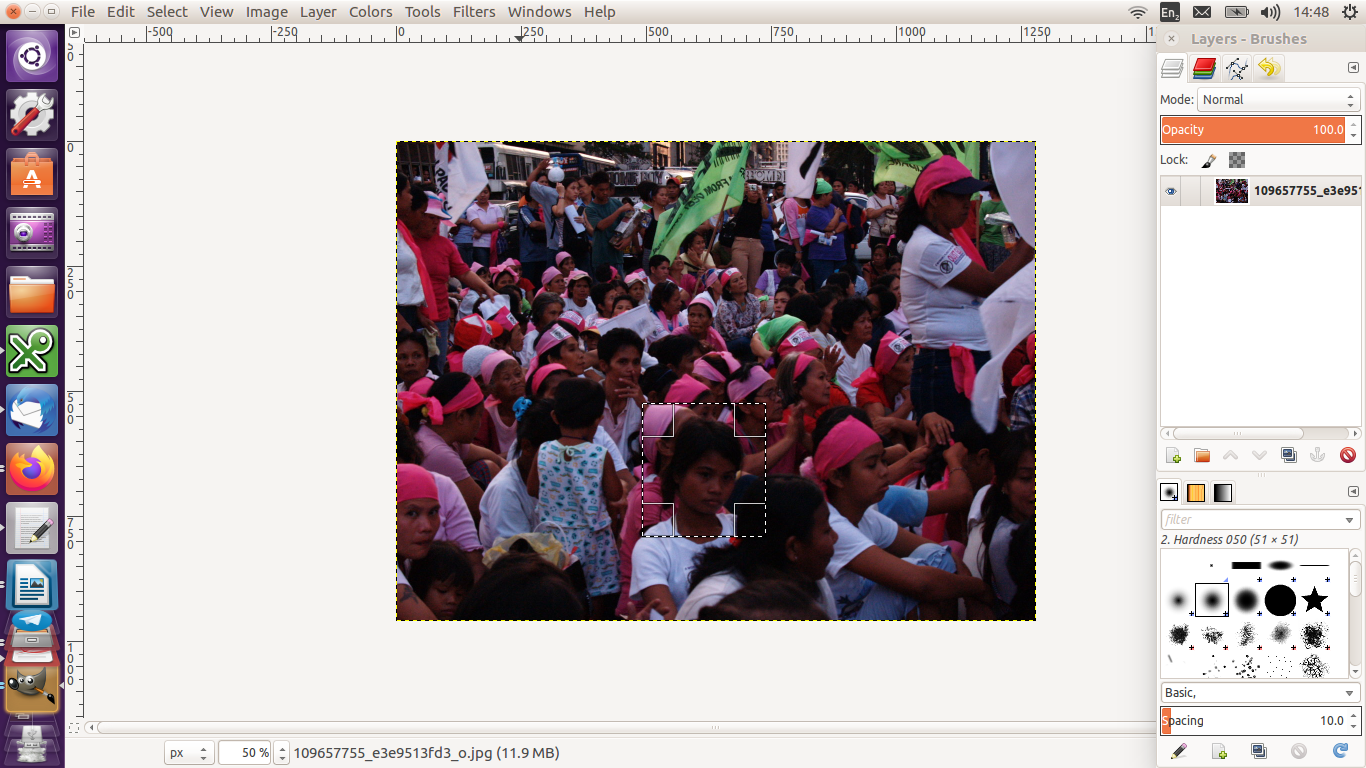

Go to Tools >> Selection Tools then choose a way to select a part of the image you want to obscure.

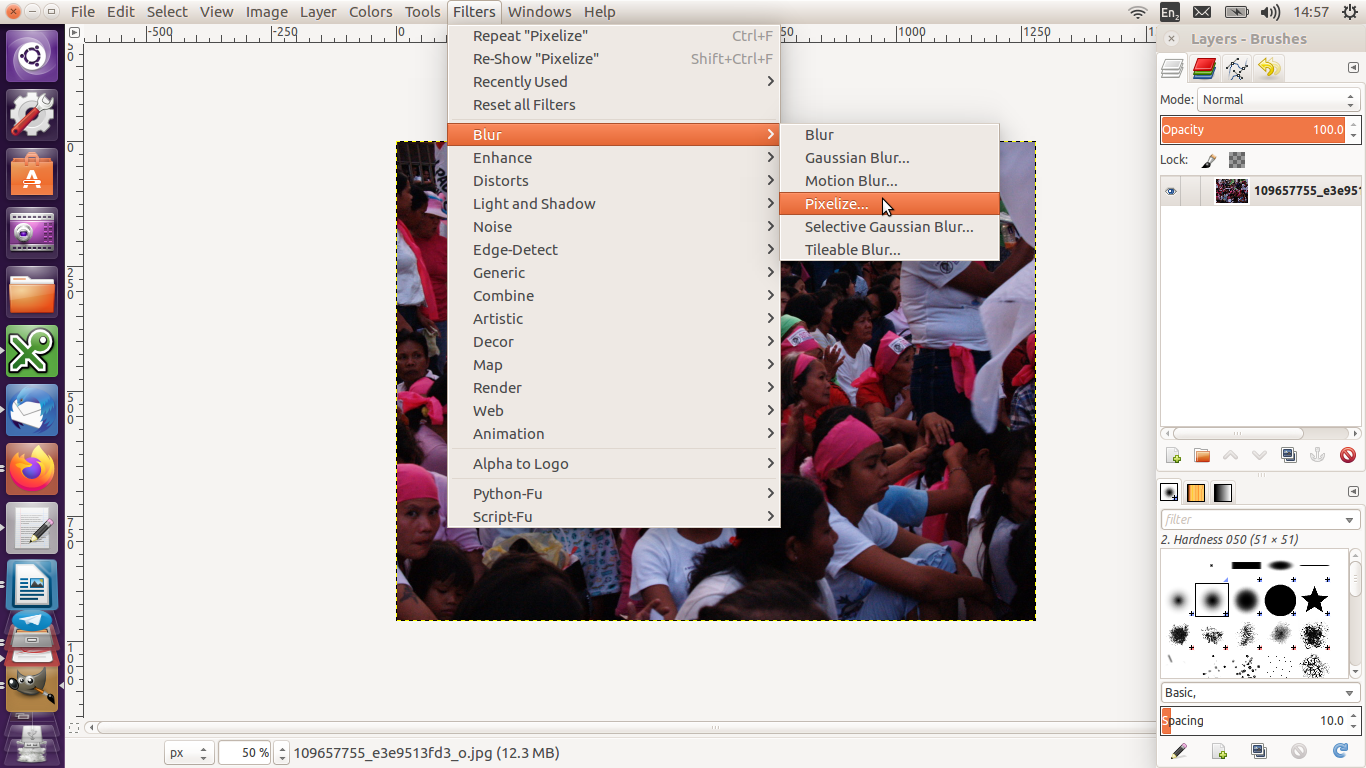

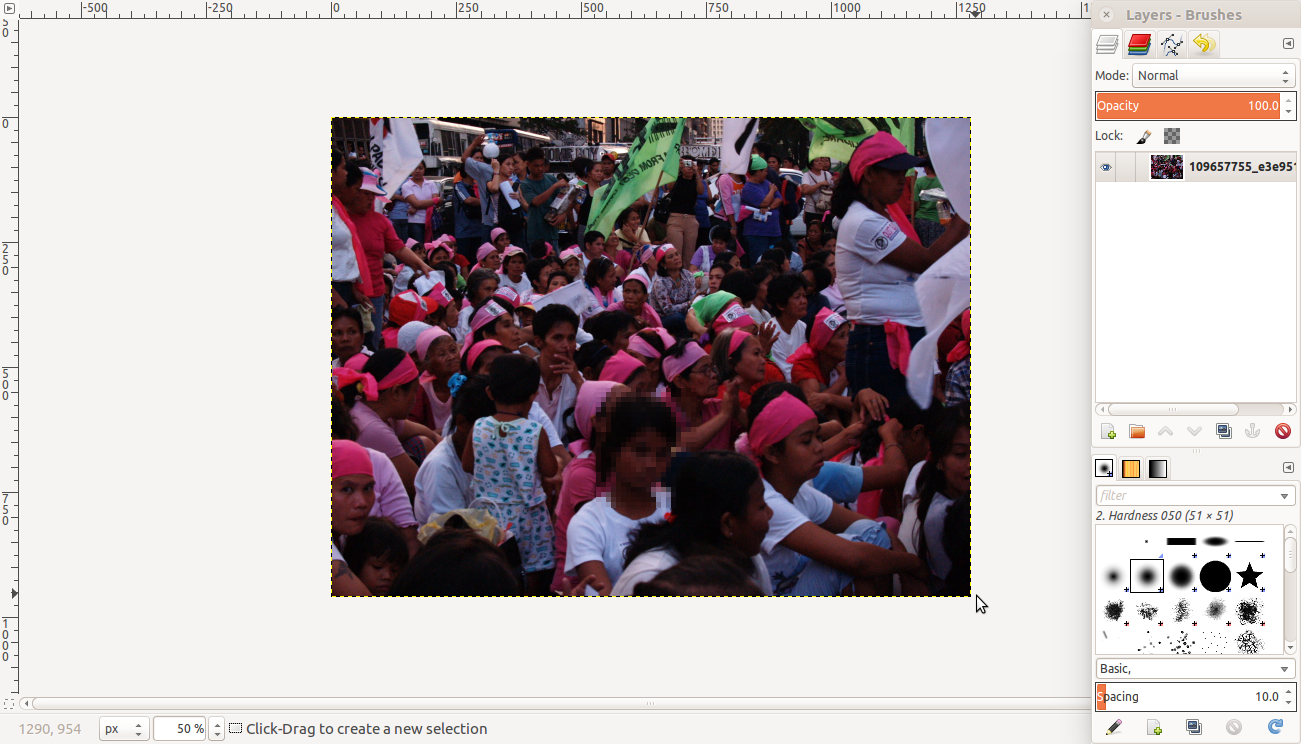

Then go to Filters >> Blur then select Pixelise. The section selected will be blurred.

You can use the other filters to obscure images.

Identifiability and metadata

“Data” refers to information. A piece of data could be a line of text, an image or a list of figures. Data is content.

“Metadata” is is information about data. Metadata provides an explanation or description of the data, which is useful for finding, using and understanding of the information. It provides the context to the image or video footage. It is like the catalogue of a library, and allows for searchability of content. There are three types of metadata:

- Descriptive

- Structural

- Administrative

Descriptive metadata is typically used for discovery and identification, as information to search and locate an object, such as title, author, subjects, keywords, publisher. A simple example of metadata for a document might include a collection of information like the author, file size, date the document was created, and keywords to describe the document. Metadata for a music file might include the artist's name, the album, and the year it was released.

How to locate metadata

Usually, metadata is stored in a different file or under a different feature. For example:

- In word documents, it is located under “Properties” of the document. Just right-click on the file.

- In Facebook, you may find this under “Your Information” and then under “Your Categories”, such as your sudden change in service providers, or the fact you turned 18 because of your activities of going to bars, getting your driving license, finally being able to vote, etc.

- In most digital cameras, they are located in the EXIF (Exchangeable Image File Format) files, which includes information on the type of camera used (the make and model of the camera, and so determines which camera took what photo), camera settings like ISO speed, shutter speed, focal length, aperture, white balance, and lens type; your GPS location where you took the photo, and when (date and time) you took the photo, and the name and build of all programs which you used to view or edit the photo.

How to remove metadata

Removing metadata from Microsoft Word, Excel, or PowerPoint

Metadata makes your content identifiable, and therefore, may make you as its producer identifiable. It leaves data tracks for anyone who is looking for more information about you to find.

As content producers, it is important to have the skill and knowhow to remove metadata from the content you produce.

Delete metadata in Word, Excel, or PowerPoint

(Source: McDowell, Guy. 2019. “How to Completely Delete Personal Metadata from Microsoft Office Documents”. Online Tech Tips, 17 June. Available at at https://www.online-tech-tips.com/ms-office-tips/how-to-completely-delete-personal-metadata-from-microsoft-office-documents/. Accessed on 9 February 2020)

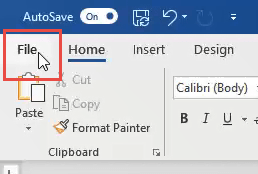

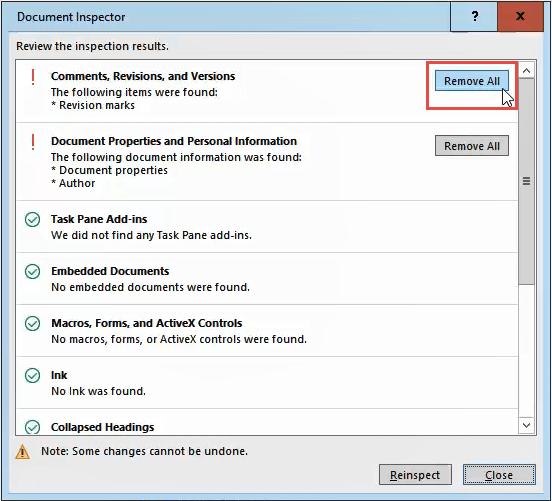

Click on on File in the top-left corner.

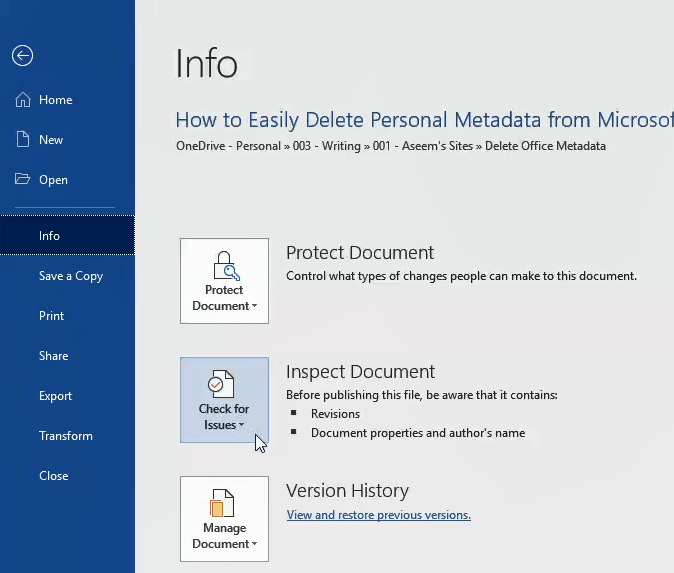

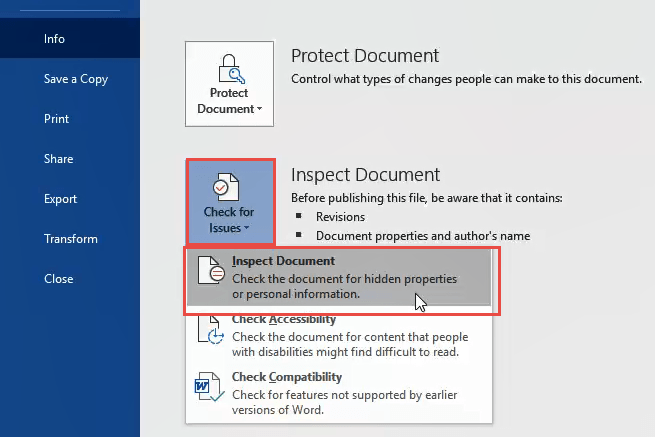

On the the Info page, click on on Check for Issues on the left, near the middle of the page.

Click on on Inspect Document. The The Document Inspector window will open.

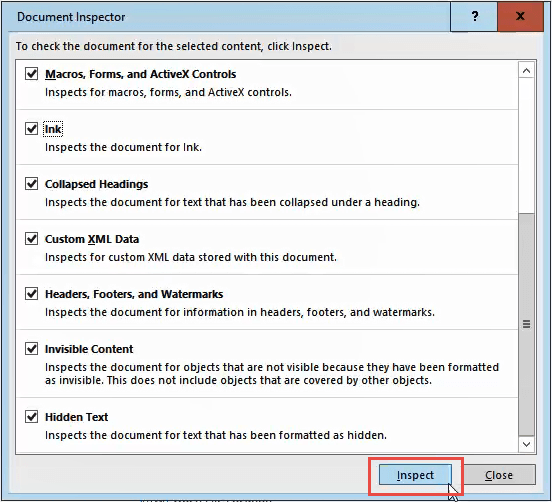

Make sure all the checkboxes in the Document Inspector are checked, then click the the Inspect button.

Once the Document Inspector is done, you’ll see information about what kind of data it found.

- A green checkmark in a circle means it found no data of that type.

- A red exclamation mark means it found data of that type.

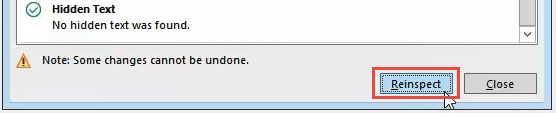

Next to that data type’s description you will see the the Remove All button.

Click on that to remove all data of that type. There may be several of these buttons, so scroll down to ensure you get all of them.

After you have removed the metadata, you may want to click the the Reinspect button, just to make sure it did not miss anything.

Save your document now to ensure the data does not get re-entered.

Removing Metadata from photos

(Source: Schmidt, Casey. 2020. “The Absolute Easiest Way to Remove Metadata From Photos”. Canto, 24 January. Available at at https://www.canto.com/blog/remove-metadata-from-photo/. Accessed on 10 February 2020).

Remove metadata from photos in Windows

There are plenty of third-party apps capable of removing metadata for you but the direct method is most efficient. It requires a few steps but it’s painless. Here is the entire process laid out as easy as possible to follow:

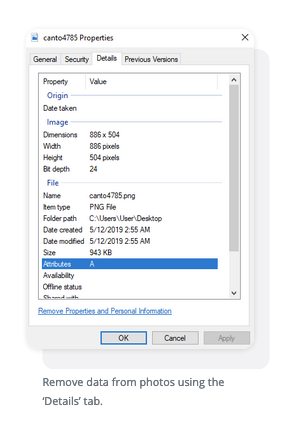

- Locate the photo you wish to alter

- Right-click it

- From the popup window, select ‘Properties’

- A window will open. Click the ‘Details’ tab at the top of the window

- From there, you’ll see a list containing attributes such as name, date, size and more. Click under the ‘Value’ portion of the elements

- For the editable data, it will allow you to type in or delete whatever you want and replace the old information

- Click ‘OK’

Remove data from photos using the ‘Details’ tab.

Remove metadata from photos in Mac

Like Windows, a Mac lets users remove remove photo metadata in a pretty straightforward fashion. Once again, here’s an easy list to guide you:

- Open the photo using ‘Preview’

- Go to ‘Tools’ in your menu

- Select ‘Show Inspector’

- Select the (i) tab

- Click the ‘Exif’ tab and remove the data

Remove metadata from photos on mobile device

iPhone

- Open the ‘Photos’ app

- Select the intended photo

- Click ‘Share’

- Select ‘ViewExif’

- Click ‘Share’

- Save the photo ‘Without Metadata’

Without using a computer connection, you can delete pic data from mobile devices.

Android

- Open the ‘Gallery’ app

- Select the intended image and click ‘More’

- Click ‘Details’

- Select ‘Edit’

- Click the ‘-’ symbol next to details you wish to delete

Both iOS and and Android have different third party apps you can download to do this process for you, like EXIF eraser.

Removing metadata from videos

(Source: Martin, Avery. “How to edit video metadata”. Techwalla. Available at at https://www.techwalla.com/articles/how-to-edit-id3-tags-in-windows-media-player. Accessed on 10 February 2020).

Windows Media Player

Step 1: Launch Windows Media Player and select the "Library" tab. Select the "Switch to Library" button when in Now Playing mode.

Step 2: Right-click on the file attribute you want to edit in the library and select the "Edit" button.

Step 3: Type the new metadata information for the attribute you selected. Press "Enter" to save your changes. If you select more than one video file, then the attribute you change applies to all of the selected video files.

Step 4: Select the "Organize" tab and select "Apply Media Information Changes" if the changes are not applied immediately.

iTunes

Step 1: Launch iTunes, right-click on the file you want to edit and select "Get Info." If you want to batch edit more than one file, highlight all of the files you want to change and right-click one of the highlighted files. Click the "Yes" button to confirm that you want to change the information for multiple files.

Step 2: Click the "Info" tab and edit any of the fields to change the metadata information. You can also select the "Video" tab to edit additional fields including the show, episode ID and description. If you selected more than one file, your changes apply to every file selected.

Step 3: Click the "OK" button to save your changes.

REMINDER: Removing metadata may help you not be identifiable with the file, but what you do with the file may increase your identifiability, such as uploading that file to your social media accounts or your cloud, or e-mailing it or the link to others.

Articles on identifiability and metadata

VICE News. 2018. “All the hidden ways Facebook ads target you”. YouTube, 13 April. Available at at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EM1IM2QUYjk. Accessed on 7 February 2020.

Matthews, Richard. 2017. “Image forensics: What do your photos and their metadata say about you?” ABC News, 23 June. Available at at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-23/what-your-photos-and-their-metadata-say-about-you/8642630. Accessed on 7 February 2020.

Lea, Martin. “How your location can be discovered from a photo you post on Facebook”. Available at

https://martinlea.com/how-your-location-can-be-discovered-from-a-photo-you-post-on-facebook/. Accessed on 10 February 2020.

CRITICAL ONGOING DEBATES: There are debates to what extent digital data about your location, like your IP address, and how you access the internet, whether through mobile phone and wifi are personal data. This is because some countries have Personal Data Protection and Privacy laws. However, companies that use metadata of their users argue that these are not personal data. Chances are there is a lot of information about you on the internet, but not all of it is clear-cut “personal data”. The IP address as mentioned is one such data, but there are also other data such as the list of websites your browser has accessed, your mobile phone’s geolocation, and so on. As far as these companies are concerned, these are metadata that provide context to your usage over the internet which allows for more targeted advertising.