Embedding digital safety in storytelling

Issues on digital safety as it applies to digital storytelling.

- Introduction

- Section 1: Digital identifiablity and content production

- Section 2: General safety considerations in choosing technology for storytelling and sharing your stories

- Section 3: Safety and online videos

- Section 4: Safety and podcasts

Introduction

This will look at some of the issues on digital safety as it applies to digital storytelling.

We use the term “victim/survivor” or “victims/survivors” of human rights violations in our effort to fully appreciate and respect how people may identify differently depending on the trauma they have experienced, and may continue to cope with. Most people fluctuate in identifying between the two terms. See for example the articles by Danielle Campoamor (21 May 2018); and Kate Simon (20 April, no year stated).

This module has four sections:

Section 1: Digital Identifiability and Content Production

This section is aimed towards expanding how we understand anonymity, non-identifiability and storytelling. This section challenges us to shift our focus on security and our safety in telling our stories by better understanding digital identifiability, that is, how recognizable you can be depending on context, the information shared, and the digital data that tells on you.

Section 2: General Safety Considerations in Content Production and Choosing Technology for Storytelling and Sharing Your Stories

This section is about ways in which a storyteller can secure themselves, the people in their stories, and the stories themselves as they create and share their stories. This section takes the trainer through the different processes and tasks involved in digital storytelling, and looks at safety considerations for each aspect.

Section 3: Safety and Online Videos

This section is about the safety, privacy and ethical considerations in creating and publishing videos online.

Section 4: Safety and Podcasts

This section focuses on safety considerations in podcasting.

Section 1: Digital identifiablity and content production

Expand our understanding of anonymity and how it is never a permanent state of non-identifiability.

Introduction

Oftentimes, we will immediately think of being anonymous when we do not want others to recognize us in the telling of our stories. There is no doubt that anonymity has played a particularly huge role in making it easier to tell difficult stories, especially when these stories speak of atrocious human rights violations and there is a continuous need to protect the storyteller or to reduce the sense of vulnerability and targeted persecution of a marginalized individual or community.

Learning objectives

This section is aimed to expand our understanding of anonymity and how it is never a permanent state of non-identifiability. “Anonymity”, in practice, generally means to be nameless and faceless. However, you can be recognizable despite being nameless and faceless and this section explains how this can be possible. The section asks that we shift our focus on security and our safety in telling our stories or first person narratives by better understanding digital identifiability. By the end of this section, the participants will:

- Gain an increased understanding of the link between anonymity and safety.

- Be able to identify the difference between anonymity and non-identifiability.

- Gain an increased understanding of the importance of establishing trustworthiness and credibility in storytelling, especially if it is in relation to discrimination, stigma and violence.

- Understand the link between metadata and safety in digital storytelling.

Creating anonymity

Creating anonymity can be done in many ways. For example, in Nepal, domestic violence survivors have resorted to speaking behind curtains in telling their stories. In most situations, vulnerable storytellers will agree to tell their stories in videos/film as long as their faces are not shown or blurred and/or their voices distorted (see Section 2: General Safety Considerations in Content Production and Choosing Technology for Storytelling and Sharing Your Stories). However, many human rights activists and storytellers strongly discourage the blurring faces or distorting of voices; the reasons why link to establishing trustworthiness and credibility of the storyteller.

Victims/survivors of human rights violations who have told stories anonymously include, among others, domestic violence survivors, those who have been trafficked, and those who face marginalization, stigmatization and religious persecution such as lesbians, gays, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) persons, people living with HIV and AIDS and women who have alleged sexual harassment against perpetrators who continue to hold power over them, likely because of employment and financial dependence of other forms.

Anonymity, specifically its adjective "anonymous", is derived from the Greek word anonymia, meaning "without a name" or "namelessness". So anonymity usually means in real terms to be nameless and faceless. However, you as the digital storyteller can be nameless and faceless in various ways.

For example, in everyday circumstances, and to her family, friends, and authorities, this is Susan Chan.

Image Source: Adapted from https://freesvg.org/group-of-people-vector-image.

IMPORTANT Note: Photographs or images of real people are not used because of the inability to get direct consent, and at this point, a real image of a person does not necessarily better facilitate understanding.

|

Creating Anonymity |

|||

SUSAN |

ANONYMOUS |

||

| Susan (a generic or common first name, without a face). | Use an avatar-type icon but with a pseudonym: “Pootie Pie” | Instead of a name or pseudonym, just refer to her as “anonymous” (without a face) | A mere silhouette |

Image Sources: Adapted from https://freesvg.org/group-of-people-vector-image

Some people have argued that namelessness, though technically correct, does not capture what is more centrally at stake in contexts that require anonymity. This is because anonymity is not necessarily equivalent to non-identifiability, and the risk of identifiability in fact increases in digital spaces.

The important idea here is that a person be non-identifiable, unreachable, or not trackable. Anonymity is seen as a technique, or a way of realising certain other values, such as privacy, or liberty. However, anonymity does not guarantee a permanent state of non-identifiability because its effectiveness is affected by space and time, or context.

In short, it is impossible to be anonymous in every single space and at every single time. So this module is to help us shift our mind sets to linking security and safety with non-identifiability rather than merely anonymity in the telling of difficult stories, and stories of human rights violations.

Storytelling and non-identifiability

There is no doubt that in many cases, anonymity is the main technique used to secure non-identifiability. From witnessing crimes and whistle-blowing to claiming human rights from violent perpetrators and perpetrators who continue to hold oppressive power over us. So in telling difficult stories, we often have to think about, quoting Foucault, to which power are we speaking our truths. Foucault was a French philosopher, whose theories examined the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. It is precisely because our difficult stories disrupt the status quo and challenge the power and privilege of some, it is important to also consider when anonymity is considered illegal in your country and under what circumstances your identity as a storyteller may have to be revealed because of the law.

This module focuses on digital storytelling and not recounting stories as victims/survivors, witnesses or whistle-blowers. The two are quite different because recounting a story as a victim/survivor, witness or as a whistle-blower requires verification of facts (by authorities and other third parties such as human rights defenders) and the establishment of the chronology of events.

The table below provides some key differences between storytelling and telling stories as victims/survivors, witnesses or whistleblowers of human rights violations/crimes, that is, telling stories for evidence-gathering.

|

The Differences between Digital Storytelling and Telling Stories as Victims/Survivors, Witnesses or Whistleblowers of Human Rights Violations/Crimes |

|

|

Telling Stories for Evidence-Gathering |

Digital Storytelling |

|

Identity has to be identifiable, at least, to selected authorities/persons and human rights defenders. |

Identity need not be identifiable |

|

Content needs to be verified by human rights organisations and/or authorities for facts/details, chronology of events, and accuracy |

Content need not be verified for facts/details, chronology of events and accuracy |

|

Content should just state what happened, and use actual visuals of persons involved (if possible), voices, places, etc. |

Content can be creatively delivered, using storyboards, and other storytelling techniques. |

Identities and non-identifiability

In using “stand-ins” to represent yourself, like avatar icons, you must always check to what extent it is identifiable with you. For example:

- A photograph of your favourite café in a specific location will render you more identifiable compared to a place you have never been to.

- Using a pseudonym that friends and others know that it is something you are fond of using or have used before, makes you identifiable. The earlier example of Susan Chan shows that she uses “Pootie Pie” as a pseudonym, but if people who know her know Susan Chan loves “Calvin and Hobbes” and in particular, Hobbes, the use of “Pootie Pie”, even though a pseudonym makes her likely identifiable.

- Using an avatar that looks like you makes you identifiable. The earlier example of Susan Chan shows that her avatar icon looks like her, short black her, similar shape of the head, etc.

- Using a photograph of your best friend or friends makes you identifiable.

- Using your initials and birthdate definitely makes you identifiable!

What you use to represent yourself as the storyteller tells a lot about you except for something generic like “anonymous” or “pseudonym”.

Some storytellers do think that their names are so generic in their social contexts that it would be difficult for people to know if it is really them, especially on social media where only handles are used or the image is non-identifiable. If you have such a name in your locality or country, do remember that while it may be a little difficult, it still means that your identity would be one of those suspected for those who have met you, know you and come across your story online. You are also identifiable by the content that you have been posting online which may refer to your regular activities, or a specific event that others know you attended.

Your identity, however, is not merely limited to your name and your face. It is your skin colour, the shape of your hands, your favourite nail polish, your favourite shoes, your worn out sandals, the way you dress, your bag, your toes, your fingers, your nose, your mouth, your eyes, your ears, the side of your face, the way you wear your hair, the kind of haircut you have, your bedroom, your study, the front of your house, the back of your house, the place you work, the road you live on, your family, your children, your partner, your friends, your neighbours, your office colleagues, any cause you are associated with, the way you walk, the way you sit, the way you stand, and the way you talk. All of these can also be easily identified with you if you have been active on social media and have been posting a lot about your life, your activities, where you go, what you do, and who you hang out with.

Identifiability and narratives

The way you talk and tell your story tells a lot about you. The way you string words together, your writing style, your favourite words and phrases, and what you usually say to express shock, anger, surprise, all tell on you.

Voice

Some of you may already be thinking “my voice is certainly identifiable with me”, but storytellers have also pointed out how the voice alone is not necessarily identifiable. This is because voices can sound similar to one another, unless your voice is a popular personality’s voice, a radio personality’s voice, a popular singer’s voice, a broadcaster journalist’s voice or a politician’s voice. Unless you have spoken in public many times, or are already a known and public/popular personality, what makes your voice identifiable is more about what you say and how you say it.

Past recounting of your story

Finally, your story will be identifiable if you have shared it before (whole or in part) or if others intimately know you and the specific experience you are speaking of. For example, an ex-husband who was violent towards you would know who you are if you speak of a particular experience, if you reference your mother, father or children. If you talk of a dress you were wearing, the kitchen where it happened, and so on.

Using storytelling techniques

What can help make you less identifiable is in telling your story in response to someone who has a similar story, someone you are unlikely to tell a story with, and someone whom your family and friends have not met. This means placing your story against another story, almost like a backdrop to your story or you may want to weave together two stories in such a way, that they reflect each other in parallel. These are tricks of storytelling and narrative development, and you may want to explore how to shape a narrative through creative storytelling techniques. Such as using a different starting point as your story, or speaking ambiguously in relation to your identity and yet tell a story that carries your truth.

REMINDER: Human rights defenders who want to use your story for witnessing or part of their evidence against a human rights crime will certainly not encourage you to use storytelling techniques. For such stories, you will likely need to talk about the specific incidence in chronological order with as much facts and clarity as possible.

Non-identifiability and credibility

One of the main reasons why storytellers should not ever blur their own faces is because you want to establish your trustworthiness with your audiences. Increasingly, blurring of faces and distortion of voices is often associated with being a criminal. Not showing your face does not mean you cannot show other parts of yourself (but do check the extent of identifiability) or use things to represent you (like a flower, a rainbow, a movement, a place, shoes, a river, etc.).

In the human rights sector, when storytellers speak of human rights violations and abuses, it is often anchored on the credibility of the human rights or intermediary organisations that publishes and distributes these stories, and ultimately uses them for policy advocacy and/or to pursue justice for the victims. For first person narratives, however, or what people generally refer to as personal storytelling, there are two key aspects that lend credibility:

- The clarity of your voice. The more muffled your voice sounds, the less likely you will come off as a trustworthy storyteller.

- The resonance people have with your story lends believability and credibility to the story content, which in turn allows people to give you the benefit of the doubt despite you not being identifiable as the storyteller.

These aspects are particularly important for individuals, groups and communities who are discriminated against or considered deviant such as people living with HIV and AIDS, sex workers, migrant workers, refugees and LGBTIQ persons.

CRITICAL ONGOING DEBATES: Some of the more recent debates around anonymity and human rights involve the use of encryption and the defense of our basic right to digital anonymity. This is because some governments, if not all governments, are keen on establishing a back door to encryption so that they can see what content you are browsing (such as a the use of HTTPS to help secure your browsing activities over the internet) and if you are a potential threat to national security. However, an interesting distinction is made between cultivating an opinion by doing the necessary reading and/or research, and expressing that opinion with conviction. These debates have serious implications for human rights storytelling because lived realities are fact, but perception of the experience itself, the negative impact, the perceived reasons for such violence and abuse (other than the actual acts of violence and abuse), can be said to be the storytellers attempt to try to make sense of the discrimination and violence, and should not also be penalized in any way for such expression.

Manipulating images to make them less identifiable

How-to steps

Manipulating images to make them less identifiable

What makes an image identifiable? The faces in it. Details that identify a location – common landmarks, street names, unique features.

Content producers need to determine before they start capturing images and footage if they want to make their content less identifiable as they take the photograph or the footage, or if they will manipulate the images and the footage for anonymity non-identifiability after they have captured and stored them.

The most safest option is for digital stories to to obscure images and footage as they are being captured. This means, even if someone gets access to the raw footage or images, the people in it are not going to be identifiable, and there will not be an original image or footage stored somewhere online or offline that they may get access to.

There are some techniques that a storyteller can use to make the people in a photo or a video footage anonymous:

- Don´t capture people´s faces but rather capture their hands or their feet as they are being interviewed.

- Use the silhouette effect – to place a strong light source behind the subject as described here: https://library.witness.org/product/concealing-identity/

- Keep identifiable location markers (street names, identifiable buildings) out of focus in taking a photo or a capturing footage

- Use filters available on Instastories, Tik-tok and Snapchat to make videos less identifiable.

- ObscuraCam is a tool developed by The Guardian Project that allows users to capture photos to make them less identifiable. This app can also use this appbe used to obscure existing photos.

Take a photo or open the image the you want to edit in ObscuraCam. Then click on the image.

What you will see is a movable and resizable box that will let you control what you want to obscure.

You will get the following options for obscuring the photo:

Pixelate: this will pixelate whatever is captured within the box

Invert: This will pixelate whatever is outside the box

Redact: This will delete whatever is in the box

Mask: This will add a mask on the image in the box

Then save the image.

ObscuraCam is especially useful if the storyteller opts to take anonymous or less identifiable photos from the start.

Note: If the storyteller opts to anonymise, meaning to make images less or non-identifiable after they are captured, they will have to take extra steps in storing their raw images and video footage more safely.

Using GIMP to create less or non-identifiable photos

Open the image to be manipulated. Analyse what you want to anonymise or make less or non-identifiable. Do you want to anonymises identifiable make faces less or non-identifiable? Or do you want to make certain elements in the photo that will make the locations or surroundings less or non- location identifiable?

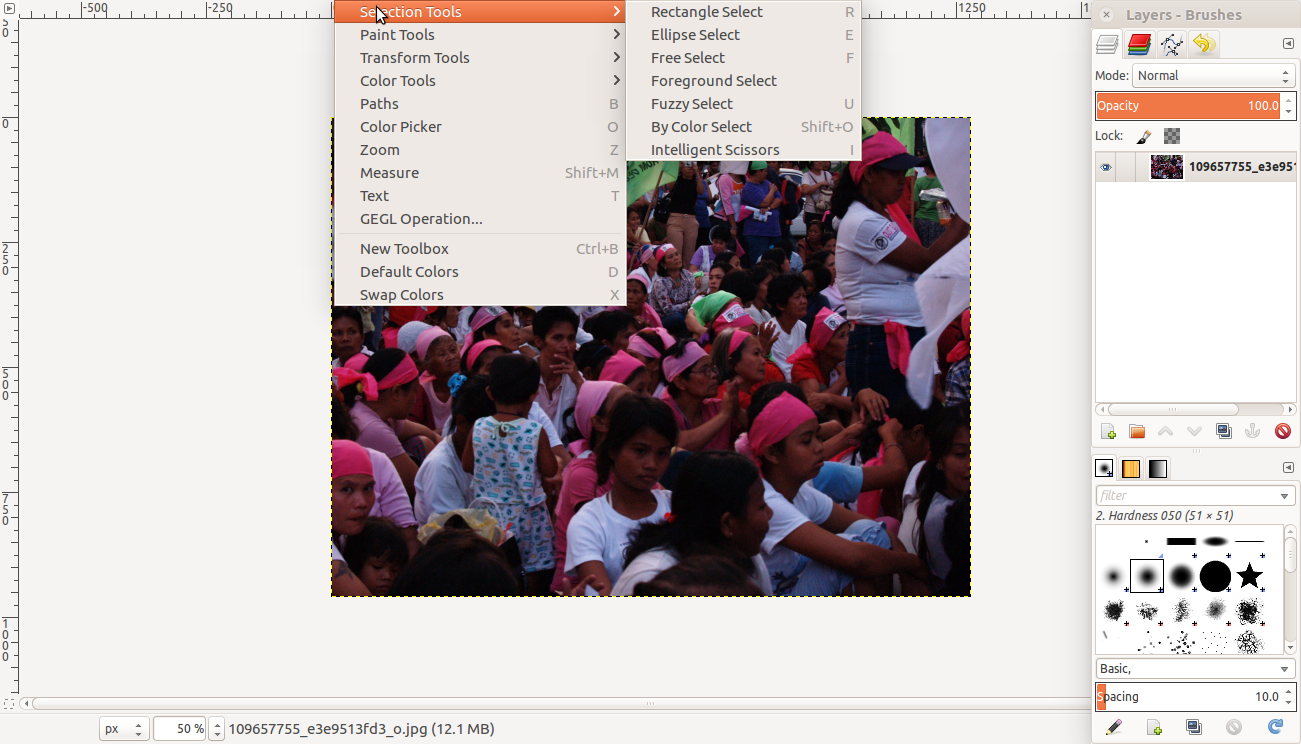

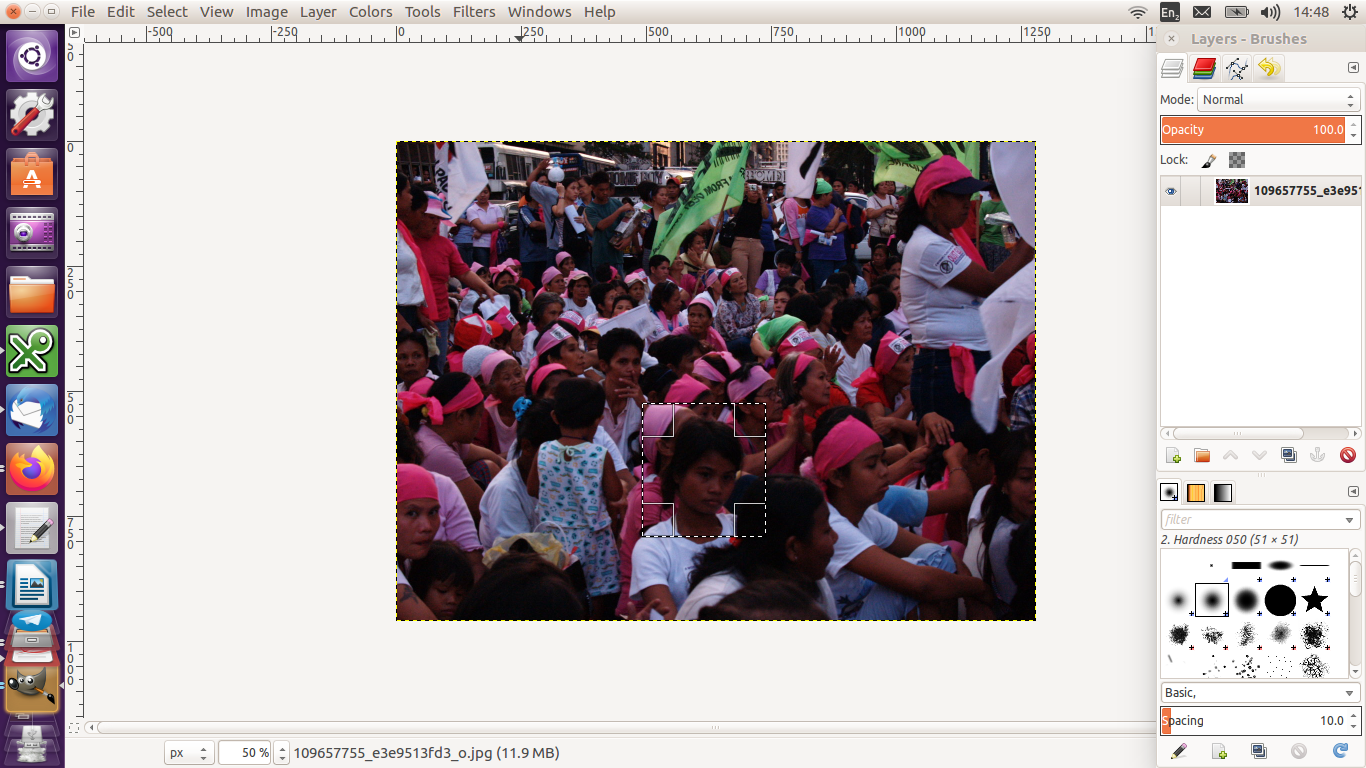

Go to Tools >> Selection Tools then choose a way to select a part of the image you want to obscure.

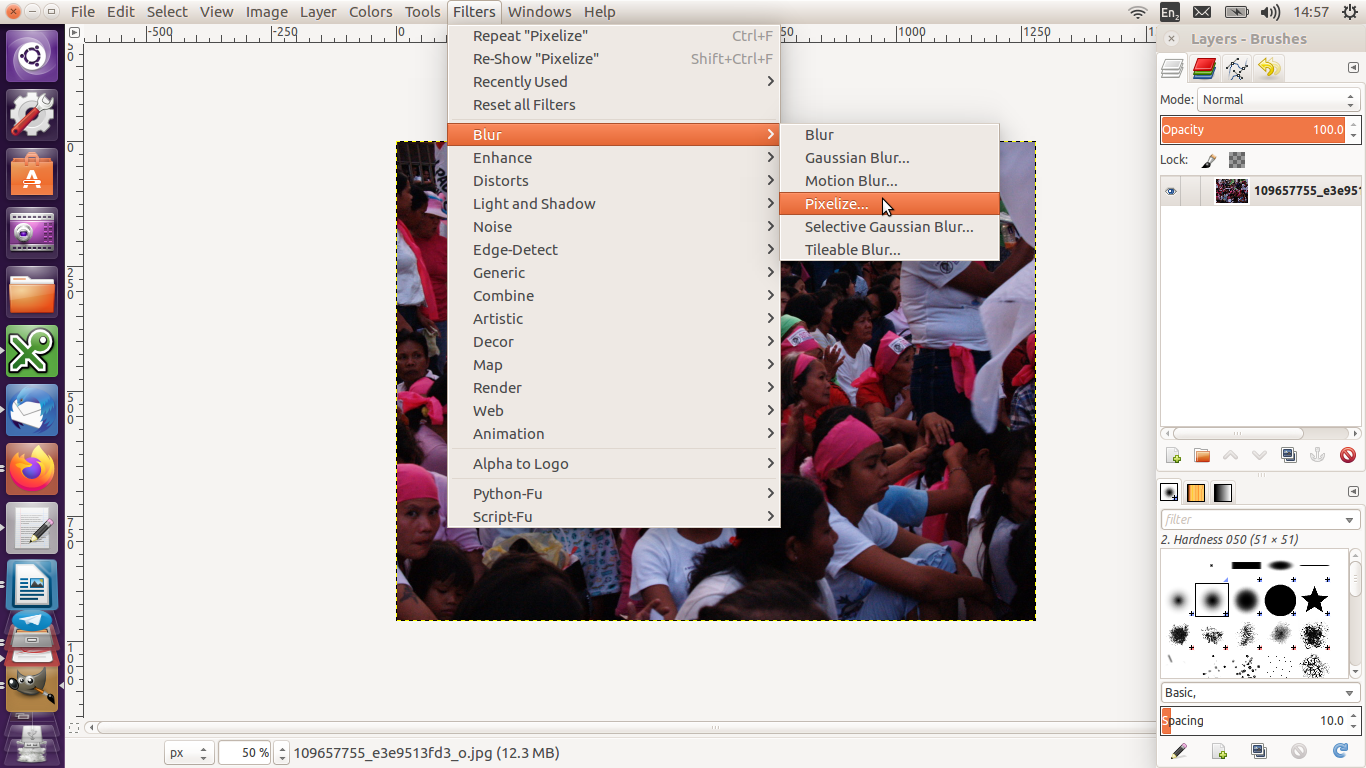

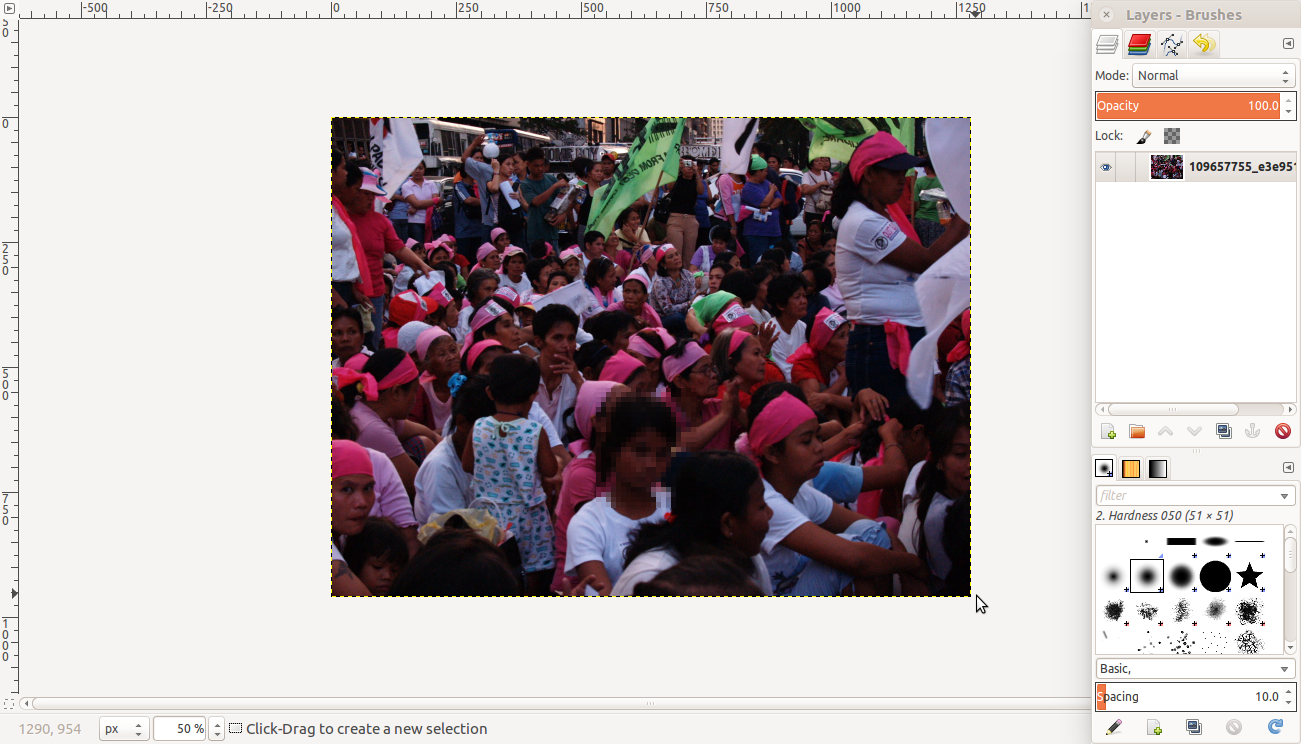

Then go to Filters >> Blur then select Pixelise. The section selected will be blurred.

You can use the other filters to obscure images.

Identifiability and metadata

“Data” refers to information. A piece of data could be a line of text, an image or a list of figures. Data is content.

“Metadata” is information about data. Metadata provides an explanation or description of the data, which is useful for finding, using and understanding of the information. It provides the context to the image or video footage. It is like the catalogue of a library, and allows for searchability of content. There are three types of metadata:

- Descriptive

- Structural

- Administrative

Descriptive metadata is typically used for discovery and identification, as information to search and locate an object, such as title, author, subjects, keywords, publisher. A simple example of metadata for a document might include a collection of information like the author, file size, date the document was created, and keywords to describe the document. Metadata for a music file might include the artist's name, the album, and the year it was released.

How to locate metadata

Usually, metadata is stored in a different file or under a different feature. For example:

- In word documents, it is located under “Properties” of the document. Just right-click on the file.

- In Facebook, you may find this under “Your Information” and then under “Your Categories”, such as your sudden change in service providers, or the fact you turned 18 because of your activities of going to bars, getting your driving license, finally being able to vote, etc.

- In most digital cameras, they are located in the EXIF (Exchangeable Image File Format) files, which includes information on the type of camera used (the make and model of the camera, and so determines which camera took what photo), camera settings like ISO speed, shutter speed, focal length, aperture, white balance, and lens type; your GPS location where you took the photo, and when (date and time) you took the photo, and the name and build of all programs which you used to view or edit the photo.

How to remove metadata

Removing metadata from Microsoft Word, Excel, or PowerPoint

Metadata makes your content identifiable, and therefore, may make you as its producer identifiable. It leaves data tracks for anyone who is looking for more information about you to find.

As content producers, it is important to have the skill and knowhow to remove metadata from the content you produce.

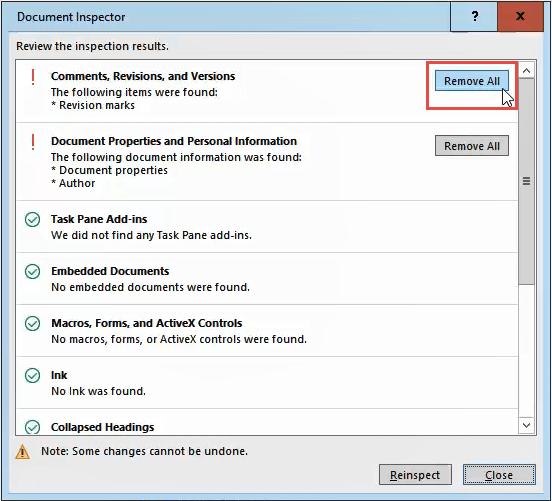

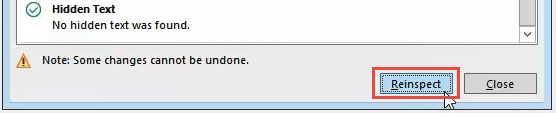

Delete metadata in Word, Excel, or PowerPoint

(Source: McDowell, Guy. 2019. “How to Completely Delete Personal Metadata from Microsoft Office Documents”. Online Tech Tips, 17 June. Available at https://www.online-tech-tips.com/ms-office-tips/how-to-completely-delete-personal-metadata-from-microsoft-office-documents/. Accessed on 9 February 2020)

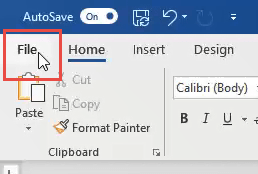

Click on File in the top-left corner.

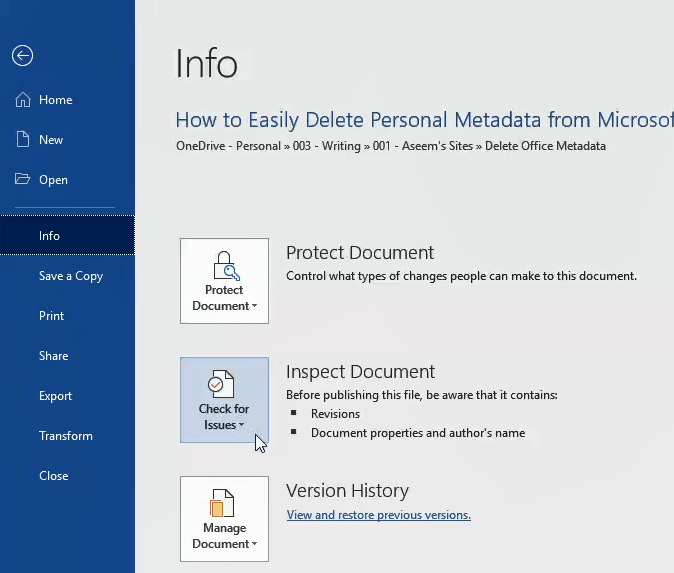

On the Info page, click on Check for Issues on the left, near the middle of the page.

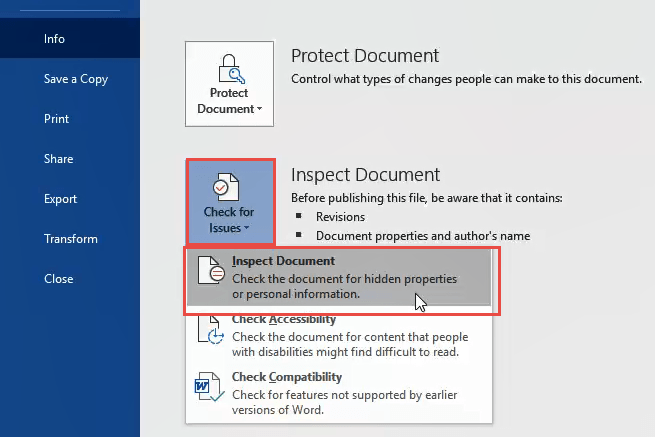

Click on Inspect Document. The Document Inspector window will open.

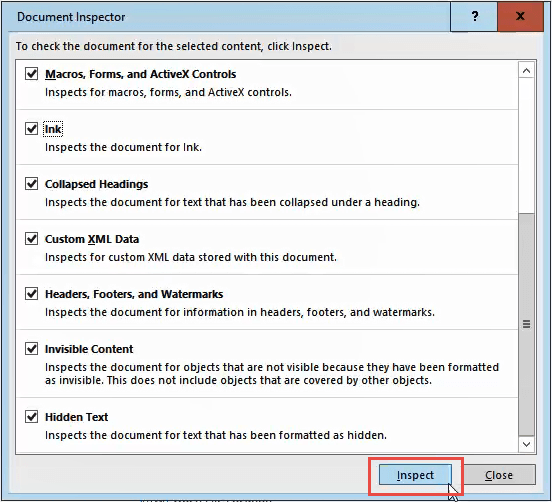

Make sure all the checkboxes in the Document Inspector are checked, then click the Inspect button.

Once the Document Inspector is done, you’ll see information about what kind of data it found.

- A green checkmark in a circle means it found no data of that type.

- A red exclamation mark means it found data of that type.

Next to that data type’s description you will see the Remove All button.

Click on that to remove all data of that type. There may be several of these buttons, so scroll down to ensure you get all of them.

After you have removed the metadata, you may want to click the Reinspect button, just to make sure it did not miss anything.

Save your document now to ensure the data does not get re-entered.

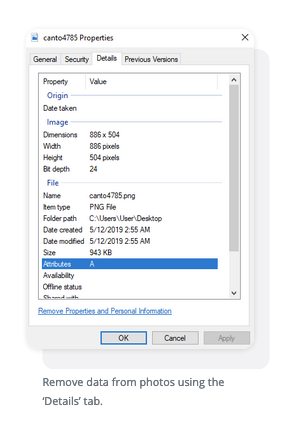

Removing Metadata from photos

(Source: Schmidt, Casey. 2020. “The Absolute Easiest Way to Remove Metadata From Photos”. Canto, 24 January. Available at https://www.canto.com/blog/remove-metadata-from-photo/. Accessed on 10 February 2020).

Remove metadata from photos in Windows

There are plenty of third-party apps capable of removing metadata for you but the direct method is most efficient. It requires a few steps but it’s painless. Here is the entire process laid out as easy as possible to follow:

- Locate the photo you wish to alter

- Right-click it

- From the popup window, select ‘Properties’

- A window will open. Click the ‘Details’ tab at the top of the window

- From there, you’ll see a list containing attributes such as name, date, size and more. Click under the ‘Value’ portion of the elements

- For the editable data, it will allow you to type in or delete whatever you want and replace the old information

- Click ‘OK’

Remove data from photos using the ‘Details’ tab.

Remove metadata from photos in Mac

Like Windows, a Mac lets users remove photo metadata in a pretty straightforward fashion. Once again, here’s an easy list to guide you:

- Open the photo using ‘Preview’

- Go to ‘Tools’ in your menu

- Select ‘Show Inspector’

- Select the (i) tab

- Click the ‘Exif’ tab and remove the data

Remove metadata from photos on mobile device

iPhone

- Open the ‘Photos’ app

- Select the intended photo

- Click ‘Share’

- Select ‘ViewExif’

- Click ‘Share’

- Save the photo ‘Without Metadata’

Without using a computer connection, you can delete pic data from mobile devices.

Android

- Open the ‘Gallery’ app

- Select the intended image and click ‘More’

- Click ‘Details’

- Select ‘Edit’

- Click the ‘-’ symbol next to details you wish to delete

Both iOS and Android have different third party apps you can download to do this process for you, like EXIF eraser.

Removing metadata from videos

(Source: Martin, Avery. “How to edit video metadata”. Techwalla. Available at https://www.techwalla.com/articles/how-to-edit-id3-tags-in-windows-media-player. Accessed on 10 February 2020).

Windows Media Player

Step 1: Launch Windows Media Player and select the "Library" tab. Select the "Switch to Library" button when in Now Playing mode.

Step 2: Right-click on the file attribute you want to edit in the library and select the "Edit" button.

Step 3: Type the new metadata information for the attribute you selected. Press "Enter" to save your changes. If you select more than one video file, then the attribute you change applies to all of the selected video files.

Step 4: Select the "Organize" tab and select "Apply Media Information Changes" if the changes are not applied immediately.

iTunes

Step 1: Launch iTunes, right-click on the file you want to edit and select "Get Info." If you want to batch edit more than one file, highlight all of the files you want to change and right-click one of the highlighted files. Click the "Yes" button to confirm that you want to change the information for multiple files.

Step 2: Click the "Info" tab and edit any of the fields to change the metadata information. You can also select the "Video" tab to edit additional fields including the show, episode ID and description. If you selected more than one file, your changes apply to every file selected.

Step 3: Click the "OK" button to save your changes.

REMINDER: Removing metadata may help you not be identifiable with the file, but what you do with the file may increase your identifiability, such as uploading that file to your social media accounts or your cloud, or e-mailing it or the link to others.

Articles on identifiability and metadata

VICE News. 2018. “All the hidden ways Facebook ads target you”. YouTube, 13 April. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EM1IM2QUYjk. Accessed on 7 February 2020.

Matthews, Richard. 2017. “Image forensics: What do your photos and their metadata say about you?” ABC News, 23 June. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-23/what-your-photos-and-their-metadata-say-about-you/8642630. Accessed on 7 February 2020.

Lea, Martin. “How your location can be discovered from a photo you post on Facebook”. Available at

https://martinlea.com/how-your-location-can-be-discovered-from-a-photo-you-post-on-facebook/. Accessed on 10 February 2020.

CRITICAL ONGOING DEBATES: There are debates to what extent digital data about your location, like your IP address, and how you access the internet, whether through mobile phone and wifi are personal data. This is because some countries have Personal Data Protection and Privacy laws. However, companies that use metadata of their users argue that these are not personal data. Chances are there is a lot of information about you on the internet, but not all of it is clear-cut “personal data”. The IP address as mentioned is one such data, but there are also other data such as the list of websites your browser has accessed, your mobile phone’s geolocation, and so on. As far as these companies are concerned, these are metadata that provide context to your usage over the internet which allows for more targeted advertising.

Section 2: General safety considerations in choosing technology for storytelling and sharing your stories

Unpacks the general safety and security considerations in digital storytelling.

Introduction

The general arc of digital storytelling is to gather photos and videos, record the narration, edit the visual and audio elements together, and then share the completes digital stories with other people. In thinking about safety and digital storytelling, storytellers are encouraged to:

Thinking about safety before beginning

When it comes to safety, there are two main considerations a storyteller should think about before production begins:

Imagining the impact of the story. The storyteller has to try to foresee how the story will affect whoever sees it. In this way, they can anticipate negative responses to their story, as well as make plans to avoid potential threats from those who are negatively affected by their story.

The Impact Field Guide has a guide to exploring a story environment for documentary films. In it, themes are categorised into four types:

FRESH: an unknown issue to your target audience and little or weak opposition.

FAMILIAR: a known issue that still has little or weak opposition.

HIDDEN: an unknown issue (to your target audience) but with strong and organised oppositional forces may require your film to prove the case - to INVESTIGATE.

ENTRENCHED: a known issue (and so possible fatigue from target audience) with strong opposition to your story and campaign - often need to offer no more new facts or assertions but simply to HUMANISE the affected communities.

It is a good idea to have storytellers think about where their stories fall into these five types, and then start thinking about what does that mean in terms of their and their story´s safety.

Some questions for storytellers to ask themselves:

- What are the positive consequences of my story? What are the negative consequences?

- Will my story hurt someone or a group of people? In what way?

- How will I feel about telling my story? Will it affect me and in what way?

- Do I have someone to speak to if telling my story makes me re-live difficult events?

- Will my story put the people in it at risk? How so?

- What can the people who are negatively impacted by story do to express their opinions? Good to think about this from what they can do to the storyteller, the people in the story, and the story itself.

Sharing of the story: Location and people. Next, based on the previous considerations, the storyteller then can think about who they want to share their story to, and how.

Generally, there are two ways that a digital story is distributed and shared. The most usual way to share digital stories is by uploading them on a commercial platform (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube). Another way to distribute digital stories is through external storage devices (DVDs, USB sticks, external hard drives).

Safety considerations in uploading digital stories on commercial platforms

The two main safety issues in sharing digital stories on commercial platforms are: the lack of control over the content and its ownership; and the lack of control over how the audience will react.

This is further explored in Section 3: Safety and Online Videos

Safety considerations in sharing via physical devices

One of the biggest issues in sharing stories via physical devices is the potential for the device to be corrupted with either malware or just reach the limit of its capacity to function. It is important therefore to have multiple copies of the content being shared, and a main back-up of the final digital story.

Safety considerations in screening your digital story

Face-to-Face Screening

If the storyteller decides to hold a face-to-face screening of their digital story, the first area of decision-making is about how private or public they want the screening to be. In order to make that decision, storytellers need to think about the following:

- What is the goal of screening this digital story? Is it to raise awareness of an issue? Is it to share personal experiences?

- Is the story going to be offensive to the viewers? Does it cover issues that people will reject because it challenges what they know or believe in?

- Will the story trigger memories in the viewers that might be difficult for them? Do you have support for these viewers from a self-care and psycho-social perspective?

- If the story will then challenge its viewers, has the storyteller taken sufficient steps to protect the people in their story to make them less identifiable and therefore, safe from repercussions?

- What can the storyteller do to prepare for possible negative, adverse reaction from the audience?

If the storyteller feels that their stories are more controversial, will put people at risk, and / or put they themselves at risk, then they can consider doing a private screening among trusted communities instead of a public one, and to be doubly sure, have a pre-registration list vetted by people whom you trust.

The next level to think about in doing face-to-to-face screenings (both private ones and public ones) is who does the storyteller want to share their stories with. In making decisions about this, the storyteller needs to reflect on a few questions:

- Who is this story for?

- Who is this story not for?

- How can I prepare the viewers of my story in managing how they will react to it?

- What can I do to prepare if sharing my story with someone offends or hurts them? What can I do to manage my own expectations about sharing my story?

- If the audience negatively reacts to my story, how can I prepare for that?

- If the audience shows minimal reactions to my story (no one loves it or think it’s a well-told story), how will I react? Will that hurt me?

- Do I need to be there as the storyteller? What risks does my presence bring me?

Learning objectives

This section aims to unpack the general safety and security considerations in digital storytelling, and to highlight strategies, tactics and decision-making points in the use of technology in the digital storytelling process.

This session will tackle the safety of the storyteller as well those in their stories, and the safety of the stories they are telling in terms of their potential impact on audiences, interested parties and authorities.

By the end of this section, the storyteller will:

- Understand why it is important to imagine the possible impact of their stories before they start making their stories

- Gain an understanding of the different safety considerations in making and sharing digital stories

- Learn about some basics of digital security as it applies to digital storytelling

It is recommended that you read the previous section on Digital Identifiability to understand the larger issues around safety and storytelling.

Safety in content gathering and production

Collection of images and videos

A typical digital story contains images and audio narration, edited together to tell a personal story. Sometimes, the storyteller will have the means to take photos, record videos and audio. Sometimes, the storyteller will have to choose to use existing photos, video and footage, and audio found online.

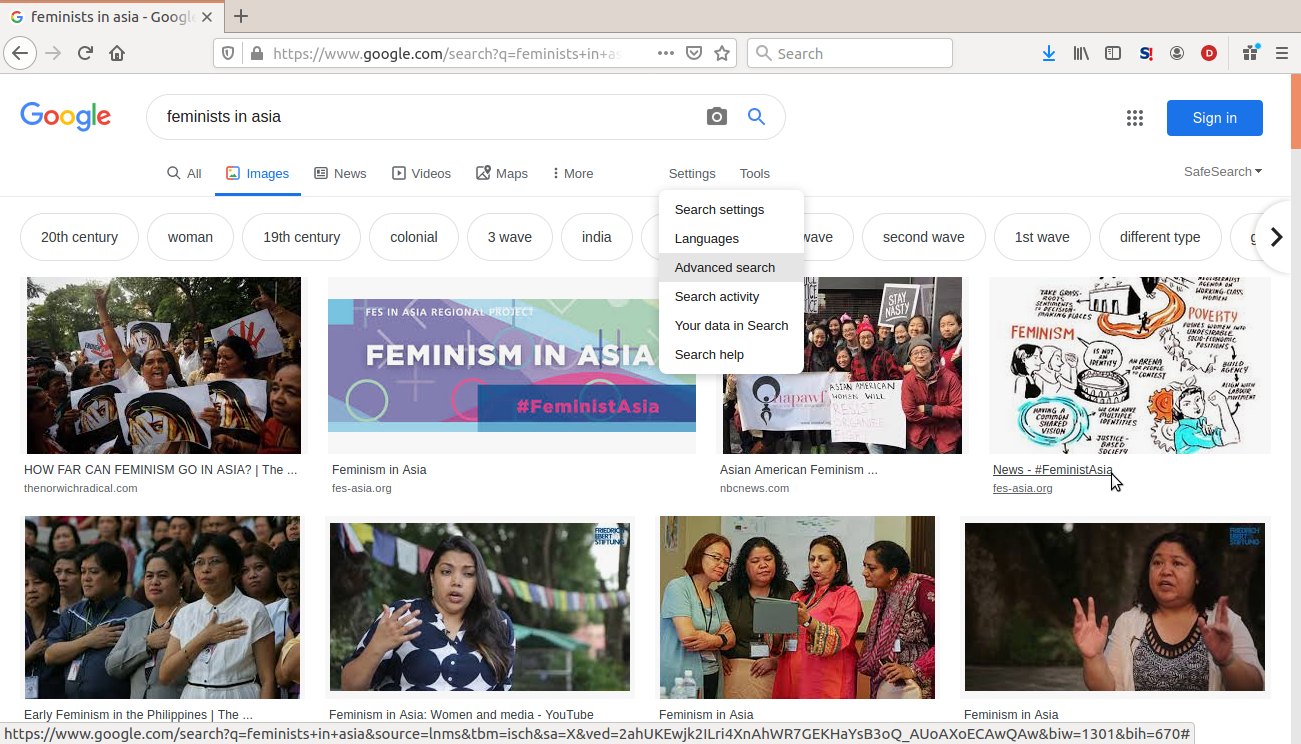

Protecting digital stories by using free to use content

Copyright – the right to use images, audio and other creative content made by others – is an important safety consideration in selecting which images, audio or video to use for a digital story. This is especially true if the storyteller wants to make their digital stories publicly available, and if the stories will cover topics and themes that people on the internet would object to. Copyright violations are often used as an excuse to take down content on the internet. All commercial platforms have guidelines and policies against the use of copyrighted material.

There are some strategies and tactics to make sure that storytellers are using material for their stories that do not violate copyright laws.

For images that are free to use and adapt:

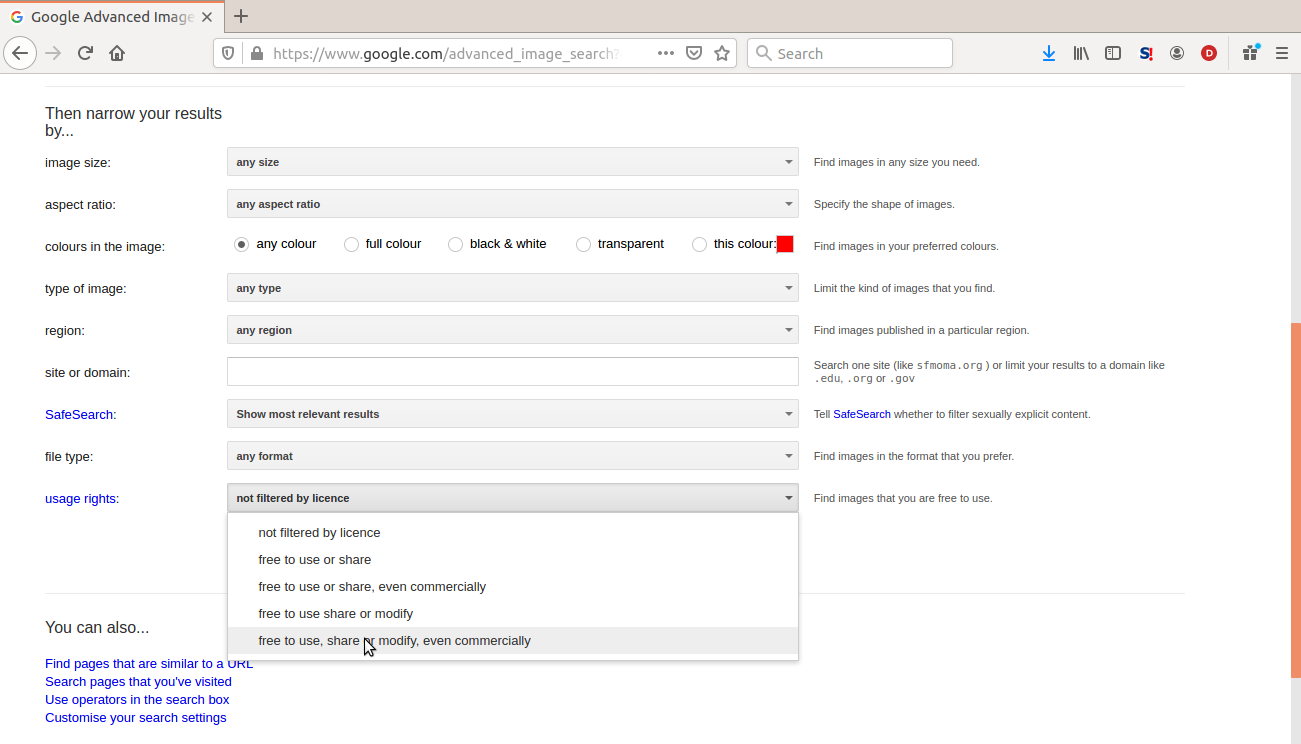

Do an advanced Google Image Search

Then select the option to only search for ¨free to use and modify commercially¨.

You can also use the following repositories of content that have Creative Commons licenses. Creative Commons licences recognize the ownership of the content creator and is an alternative to the current accepted practices of Intellectual Property Rights, where ownership tends to lie largely with large companies. It allows the original content creator to decide who can use the content, and how it can be used (non-commercial or commercial) or modified. The most unique features of Creative Commons licences is how it ensures attribution to the original content creator and that the same practice of copyright terms and conditions must be honoured and extended to others by those who use and/or modify the original content. To learn more about Creative Commons, see https://creativecommons.org/about/.

Creative Commons licences recognize the ownership of the content creator and is an alternative to the current accepted practices of Intellectual Property Rights, where ownership tends to lie largely with large companies. It allows the original content creator to decide who can use the content, and how it can be used (non-commercial or commercial) or modified. The most unique features of Creative Commons licences is how it ensures attribution to the original content creator and that the same practice of copyright terms and conditions must be honoured and extended to others by those who use and/or modify the original content.

- Creative Commons Search: https://search.creativecommons.org/

- Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

- Internet Archive: https://archive.org/

- The Public Domain Project https://www.pond5.com/free. Here you can download historical content that are free.

- Pexels Creative Commons section: https://www.pexels.com/creative-commons-images/

- Flickr´s Creative Commons section: https://www.flickr.com/creativecommons/

Free audio sites:

While these sites generally have content that is free to use, edit and adapt, e. Each material to be used has to be checked for the specifics of their copyright permissions. Some of the materials are free to use and edit / adapt but requires crediting the original creator of the content. Some do not.

It is also recommended that storyteller adds credits at the end of their story to attribute the content that they used in telling their stories.

Protecting storage devices

It is important to protect the storage devices the storyteller will be using throughout the process. Devices should be password protected, in order to secure the files within it.

Password protect computers with a more than twelve character password.

For mobile phones, there are different ways to lock the screen.

- PIN: four to six number combination

- Pattern Lock: Create a pattern with dots on your screen

- Password: any combination of numbers, letters and special characters

- Biometric locks: fingerprint, face recognition or retinal scanning to unlock your phone

Out of the options, having a secure password (more than twelve alphanumeric characters) is the safest.

- Computers and mobiles phones can also be encrypted. This provides a much more secure way to protect devices.

- According to Apple, all their computers and iPhones are encrypted by default.

- Windows machines have Bit Defender that is available on Windows 8 to later versions.

- For Android, the user has to encrypt their phones by going through the Settings.

As a digital storytelling trainer, it is good to encourage the storytellers you will be working with to do this before the training.

Backing-up content

It is a good idea to create copies of collected and created content and materials for stories in a separate device from the main working device at different points in the storymaking process. This protects the storyteller from any unforeseen and unpreventable issues like device failure or loss of files.

For example, having a USB drive where the storyteller can create a back-up of the directories of their story content. Or having an external hard disk. Depending on the sensitivity of the story as well as the internet access available to the storyteller, they can also consider backing up to cloud storage services like Google Drive and iCloud.

It is important for storytellers to determine when they are backing up their materials. Depending on the time that a storyteller is collecting content for their digital story and producing it, it is usually recommended to back up material when the collection or creation phase is over – before they work on editing or manipulating their content. Then once an edit of a material is done, there should be a back up of that. Then a back up of the final story. Do be mindful that sometimes you may realise that you do not have the content you need to create the final digital story, but do not forget to back up after all additional material is collected or created.

Section 3: Safety and online videos

Ways in which videos are created and shared online.

Introduction

Digital stories, generally, are short stories created by combining recorded narrative with images (still or moving. In short, they are a type of video as they merge audio and visual elements to tell as story.

Generally, there are two ways of sharing videos on the internet.

Produce offline, then publish online

This method is for both long-form and short-form videos. There are video-sharing sites where long-form videos can be published (YouTube, Vimeo, Daily Motion). Most popular social media platforms allow short-form videos (Twitter, Facebook, Insta-Stories).

Livestreaming: record as you post online

This is when a user records an event or an activity, and shares it as they are recording it. Some livestreaming sites (Bambuser, YouTube Live, Twitch) allow for longer streaming time. Platforms like Instagram Live, Facebook Live and Periscope (owned by Twitter) allow for shorter streaming time. Some livestreaming platforms like Instagram Live and SnapChat delete the streamed videos within a given period of time.

This section will tackle the safety consideration in both types of online video sharing.

Learning objectives

This section focuses on the ways in which videos are created and shared online. By the end of this section, it is expected that the storyteller will:

- Have an appreciation of the safety concerns in publishing videos on online platforms

- Have an understanding of how to better select video sharing platforms

Safety issues in sharing digital stories online

There are three areas of safety issues: ownership over the digital stories, what do digital storytelling platforms know about the storytellers, and safety responses of digital storytelling platforms.

First things, first: Who owns the stories?

The storyteller owns the stories -- a simple enough answer.

But when it is a digital story that they create, the answer is not that simple.

The nature of ¨digital¨ means that a storyteller has to concede some control over the ownership of their stories. Digital content can easily be copied or downloaded into individual computers or mobile phones, and then shared on other platforms.

There are software and browser plug-ins that allow people to download YouTube videos into their own machines, allowing them the ability to be able to edit videos. In that case, who then owns the story? If the user, who downloaded a video, edits it in a way that the original storyteller did not intend, is there a recourse for the storyteller?

For example, Instagram Live stories are supposed to be temporary, they are not permanent. By default, an Instagram Live video will remain on the user´s page for one month, then it is deleted. But nothing stops followers of that user from downloading those temporary Instagram Live feeds, and then sharing them on other social platforms or private online conversations -- without the knowledge and consent of the person who originally posted that story.

When a storyteller uses a commercial platform like Facebook, Instagram (which Facebook owns), YouTube (Google) or Twitter, then it becomes more complex.

According to Facebook´s license agreement, they lose ownership of content when the user deletes it. However, they clearly state that they cannot do anything about other accounts that have shared that content. In essence, because Facebook shares ownership of content with its users, they still own that deleted content which could still sit on their servers.

Secondly, what do these platforms know about the storyteller?

More than that, these platforms collect and own other data in relation to the storyteller and their stories. They also own the connections between those different data sets, and are able to share them with Third Party companies for marketing and advertising purposes. These platforms have also reported that they get approached by States for information about their users and their activities on these platforms, usually for criminal investigation1. Facebook, in fact, produces its own report on government requests for user data2.

These considerations also apply for when an user stores or backs-up their data on the cloud (for example, Google Drive and Dropbox). A storyteller might not be using video-sharing platforms to publish their stories, but they might be using internet platforms to store the raw materials for their digital stories (the images, the script, the audio recordings).

While over the years, these platforms have developed guidelines about government requests, they retain the right to change these guidelines and not inform their users about changes. More than that, this shows that these internet companies hold a lot of data, connections among data sets that provide accurate profile of users not only in terms of identity, but likes, preferences, social network and activities, and information about their users.

There are ways to obscure identity on the internet, to make connections between stories and the identities of their storytellers less obvious. Depending on how the storyteller foresees the impact of their stories, then they can take steps in protecting themselves before they share their stories on this platforms.

Thirdly, what do these platforms do when a storyteller is harassed on their platforms?

Online gender-based violence has been a growing trend on the internet for over a decade. It has escalated in a way where it is commonplace for women, queer and non-binary identities on the internet are attacked for their sexuality, appearance, opinions and even when they share lived experiences. These platforms do the minimum in response to this kind of harassment. In their End User License Agreement, they hold no liability for any harm caused over their platforms.

In simple terms, if a storyteller is harassed for their story in any of those platforms, they are on their own. At most, they can report incidents and block specific accounts, but how it gets addressed beyond that is at the platform´s discretion.

Sometimes because of the lack of knowledge of local contexts, the politics of those who own Facebook and their understanding of the exercise of freedom of speech, the common response is to tell you, the harassed victim, to block the abuser or to make your posts private. However, this only means that you are being abused in spaces where you are not privy to assess the extent of harm done against you.

Given the gaps in platform response to online harassment, it is also important to note that many feminists and women´s rights activists have found other ways to respond to the abuse and harassment they and other women and LGBTQI identities have experienced. Very often, these activists rally around someone who is being harassed online, either to report the harassers or directly respond to them. A storyteller, if they are harassed online for their stories, can reach out to feminists and activists for support.

Safety considerations in choosing platforms for video sharing

General digital security considerations

- Does the platform allow users to maintain strong passwords (more than 12 character passwords)? Better, does it tell the user that the passwords that they are using are not secure?

- Does the platform use HTTPS throughout its site? HTTPS is an encryption protocol that protects information as it travels through the internet.

Platform-specific considerations

- Will the platform allow users to control who can see their videos?

- Does the platform have a privacy setting for video content?

- Does the platform allow a user to control who can comment on their videos?

- Does the platform allow for downloading or copying of users videos without their consent?

- Does the platform allow the user to delete their videos from the platform? And would this mean that if it was shared or posted elsewhere (through the same platform) that the videos would automatically be deleted as well?

1 See for example:

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/aug/27/facebook-government-user-requests;

https://techcrunch.com/2017/12/18/government-requests-for-facebook-user-data-continue-to-increase-worldwide/; and

https://techcrunch.com/2019/11/13/facebook-says-government-demands-for-user-data-are-at-a-record-high/

2 See https://govtrequests.facebook.com/government-data-requests

Section 4: Safety and podcasts

Safety considerations in podcasting

Introduction

Podcasts is is are usually part of a series of digital audio content that is made available for users to download or stream. Podcasts are episodic – each installment is complete, with a start and an end, that contributes to a larger theme (e.g. issue-themed feature news, a specific topic) or story.

Learning objectives

This section will be about unpacking some safety considerations in podcasting. Specifically, around how to mitigate some potential risks as well as how a storyteller can have more control over their content by choosing the right platform for their needs.

Preparing to podcast safely

The common format of a podcast is the main host having a conversation with a person who has experience and knowledge on a certain topic or theme. But increasingly, podcasting is being used to tell stories.

Storytellers who are considering podcasting as a way to tell their stories will have to consider some things in order to do it more safely. Generally, many podcasters use their real names and only involve others who do the same. Podcasts being all audio provides a sense level of non-identifiability because it is faceless.

However, depending on how sensitive the storyteller´s theme is as a storyteller, they you might want to consider ways in which to control their identifiability as they you podcast. Theirs and the people they you want to involved in it.

It is important for the storyteller to imagine the impact of their podcasts will be on themselves and their guests, and to try to mitigate negative consequences. These negative consequences could be:

- harassment of the storyteller or their guests from people who do not share their opinion

- re-traumatising the interviewee

- exposing the identity survivor of a human rights violation or sexual abuse and causing them harm

- re-traumatising listeners

If the theme of a podcast is too sensitive, for example on issues of equal access to justice or the weaknesses of Sharia legal systems, the storyteller might want to consider having a different format for their podcast. In recent years, some podcast producers have used fictionalised content to engage more serious topics, or to share stories. Instead of using the more standard conversation format, they instead write scripts for audio dramas. These range from short stories (each episode is a short story) to longer fictional stories (each episode is a chapter).

Whether or not the storyteller will use the more standard podcast format, or do a fictional podcast, they should still consider the following questions before they start podcasting:

- What is the podcast about? Are there going to be themes in it that will put the storyteller or the guests at risk?

- Who will be the guests on the podcasts? Are they agreeable to be identifiable? If they prefer to use a pseudonym, you as the one creating the podcast will have to be mindful of not slipping up and using your guest’s real name. If your guest prefers to be anonymous, it is common to still have some kind of reference because it is natural to want to call the person by name. So a generic pseudonym like ¨friend¨, ¨Person A¨ or a generic name in your culturecould help.

- What is already available on the internet about the storyteller? Is there information about the storyteller that can be used to harass them or those close to them? The storyteller would need to do this with people who will be guests in their podcasts as well.

It is also recommended that a storyteller gets a separate email address (not their personal or their work email addresses) for their podcasting use. They can use a free and secure service like https://proton.me or TutaNota for this. This will protect them from possible spamming of their personal accounts as well as help protect their identities on the internet.

Here's an example of a story that can be seen as very controversial, about a lesbian in a straight marriage, podcast produced by Juana Jaafar.

Juana Jaafar. 2016. “On being lesbian in a straight marriage”. JuanaJaafar.net, 21 July. http://www.juanajaafar.net/2016/07/on-being-lesbian-in-a-straight-marriage/

Safety considerations in choosing podcast hosting providers

As with any other forms of digital content that is meant to be shared, where that content is hosted (stored and shared) is an important consideration. There are a lot of podcast host services available. Most of them for a fee. Some are free – with a lot of limitations about length of the podcasts, size of the audio files, and permanence of the files on the host server.

In selecting podcast hosting providers, a storyteller must consider the following:

User control over podcasts

Will they be able to delete, edit, and / or archive episodes?

Some free podcast hosts delete podcasts after a month. If you want to archive them, ensure you have back up, but where and how you store these could have further security issues too.

Is the podcast host able to delete users content?

The storyteller needs to read the End User License Agreement of the podcast hosting provider to know if the service will be able to delete content without the user´s permission. Sometimes services will try to detect copyrighted materials or are against certain topics being promoted, like the human rights of LGBTIQ persons or environmental issues where accusations of wrong-doing may be deemed as defamatory.

Audience engagement and management

Where do the podcast hosting provider automatically feed the podcasts?

Some of them automatically feed the podcast to more mainstream platforms (iTunes, Spotify), which means the podcaster will not have that much control over who gets to listen to their podcasts. This also means the podcasts will likely reach a wider audience. The storyteller needs to consider how much they are able to control who listens to their podcasts.

Will the podcast hosting service allow the podcaster to control the RSS feed of their own podcasts?

An RSS (Rich Site Summary or Real Simple Syndication) feed is a list of updates of new content from websites. The most common use of RSS feeds is in news content. This allows a user to get new content from different news sites using one application (examples of RSS readers, https://fossbytes.com/best-rss-reader-apps/) instead of going to these websites one-by-one for updates. Podcasting generally uses RSS feeds in order for podcasters to automatically update their podcasts on different podcasting applications (i.e., Spotify, Stitcher, iTunes). Most podcasting hosting services automatically generate RSS feeds for podcasts and share them with more popular apps. This is important if the storyteller wants to limit how their podcasts are released. What this means is that the podcast hosting service will not automatically share the podcasts with mainstream platforms but rather allow the podcaster to share it themselves.

General hosting safety

- Does the podcast have site-wide HTTPS?

- Do they allow for strong passwords? 12+ characters

- What do they publish about their users? Do they publish real names of their users? Or usernames? It is safer if the host only shares user names and not actual names of their users publicly and on their sites.

Related links

Fiction Podcasts: https://www.thepodcasthost.com/fiction-podcasts/story-format/

How to Protect Your Privacy While Podcasting: https://theaudacitytopodcast.com/how-to-protect-your-privacy-while-podcasting-tap288/

How to Stay Safe and Secure in Podcasting: https://theaudacitytopodcast.com/how-to-stay-safe-and-secure-in-podcasting-tap289/

Why you need your own privacy polices in podcasting: https://theaudacitytopodcast.com/tap079-why-you-need-your-own-privacy-policies-disclosures-and-releases-for-blogging-or-podcasting/