(en) FTX: Safety Reboot

The FTX: Safety Reboot is a training curriculum made up of several modules for trainers who work with women’s rights and sexual rights activists to use the internet safely, creatively and strategically.

- Introduction

- Welcome to the FTX: Safety reboot

- Training modules and getting started

- Resources to prepare your training sessions

- Online gender-based violence

- Introduction and learning objectives

- Learning activities and learning paths

- Online GBV or not? [starter activity]

- Deconstructing online GBV [deepening activity]

- Story circle on online GBV [deepening activity]

- Take Back the Tech! Game [tactical activity]

- Planning response to online GBV [tactical activity]

- Meme this! [tactical activity]

- Mapping digital safety [tactical activity]

- Resources | Links | Further reading

- Creating safe online spaces

- Introduction and learning objectives

- Learning activities, learning paths and further reading

- Unpacking "safe" - visioning exercise [starter activity]

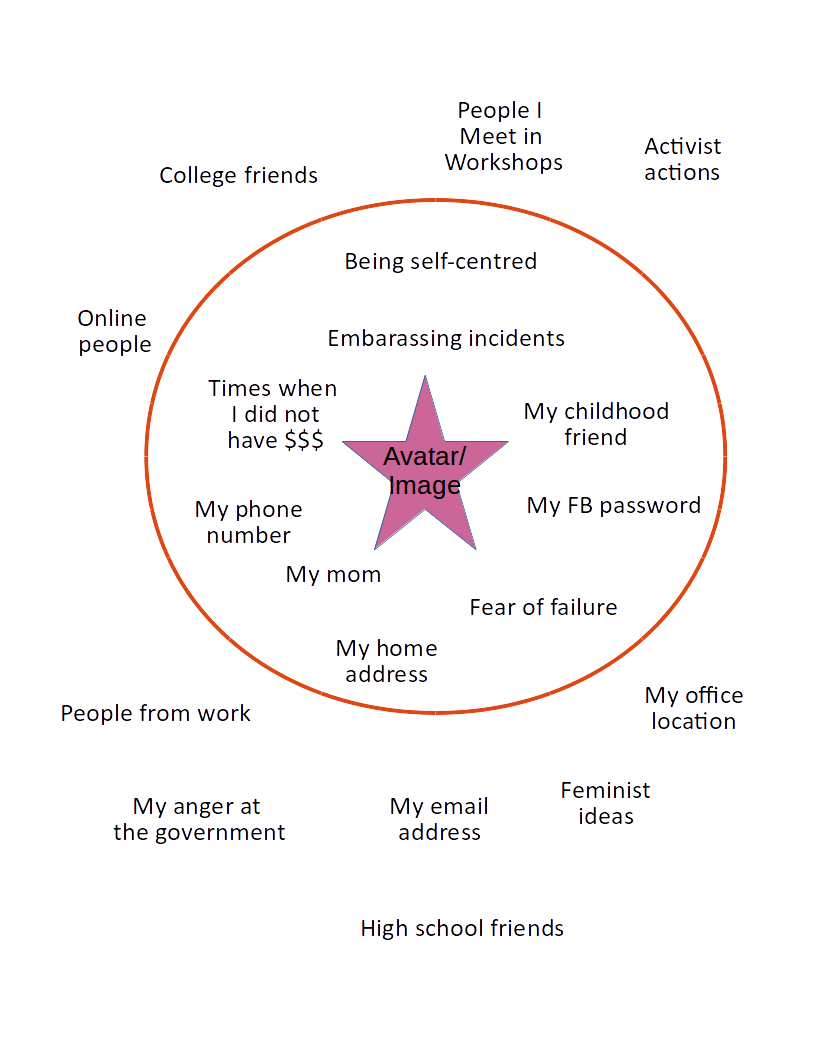

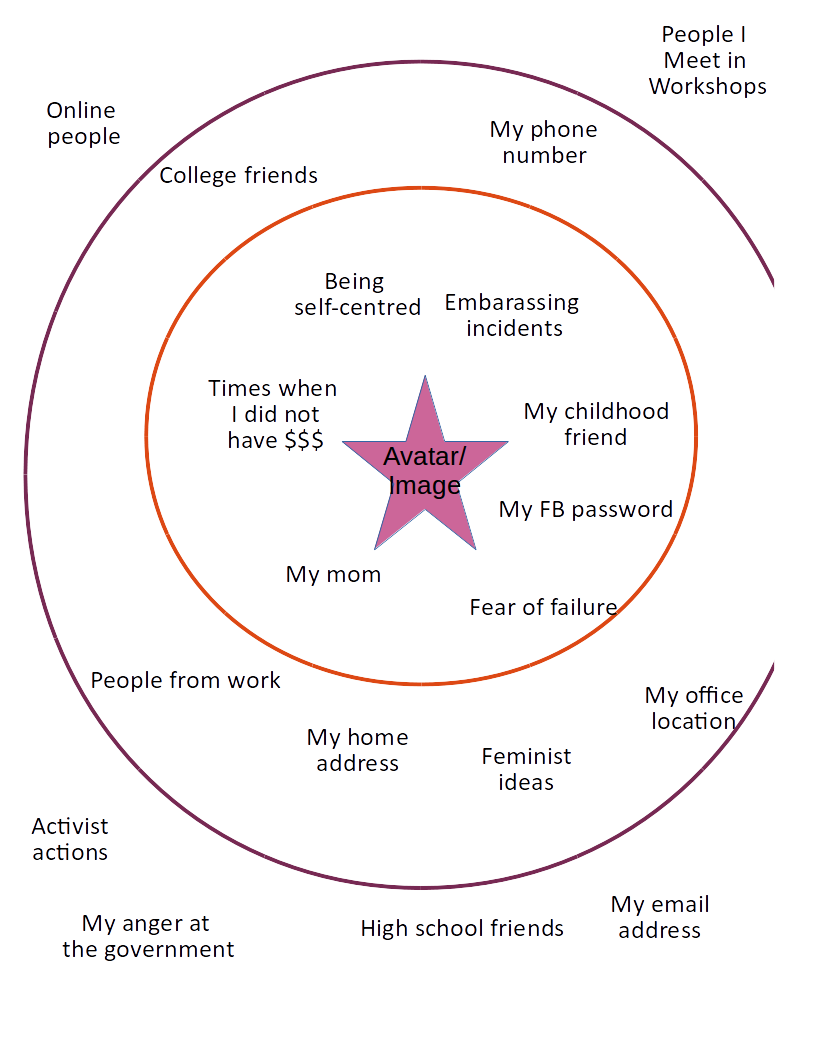

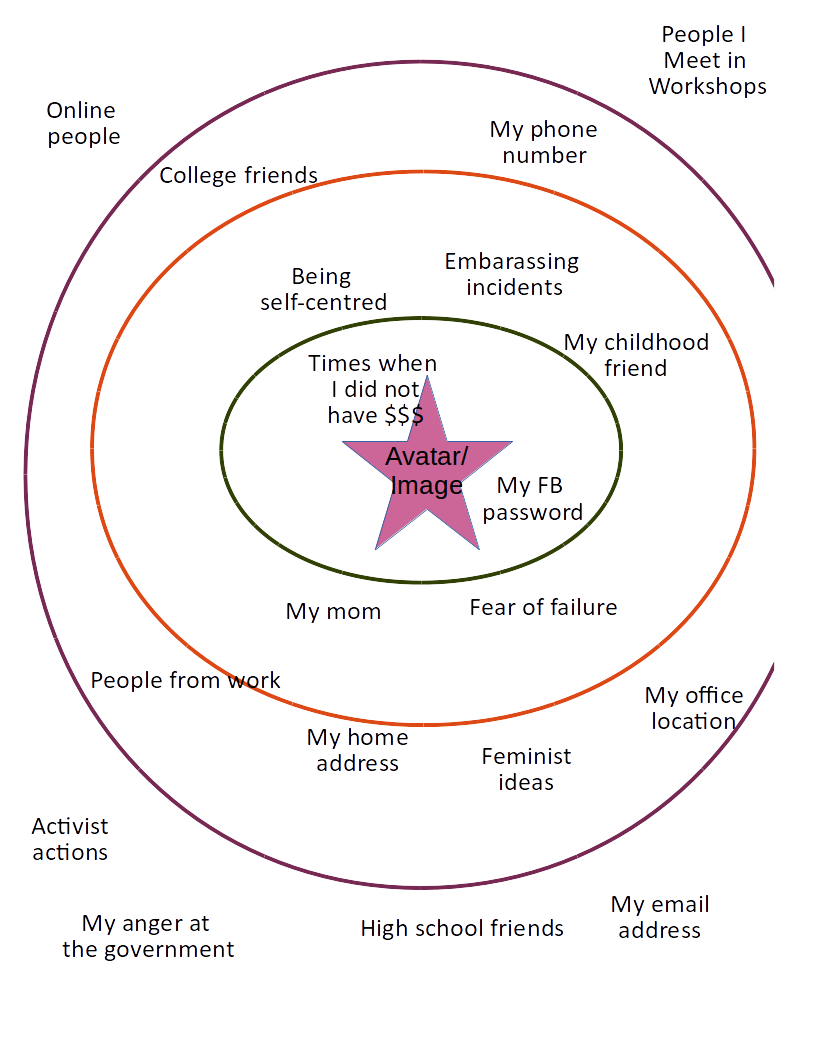

- The bubble - visualisation exercise [starter activity]

- Develop your internet dream place [starter activity]

- Photo-social-network [starter activity]

- The cloud [starter activity]

- Visioning + discussion: Settings + permissions [starter activity]

- Input + discussion: Privacy, consent and safety [deepening activity]

- Input + activity: Online safety "rules" [deepening activity]

- Making online spaces safer [tactical activity]

- Alternative tools for networking and communications [tactical activity]

- Mobile safety

- Introduction and learning objectives

- Learning activities, learning paths and further reading

- Mobiles, intimacy, gendered access and safety [starter activity]

- Making a mobile timeline [starter activity]

- Himalaya trekking [starter activity]

- Collecting phones [starter activity]

- Me and my mobile [starter activity]

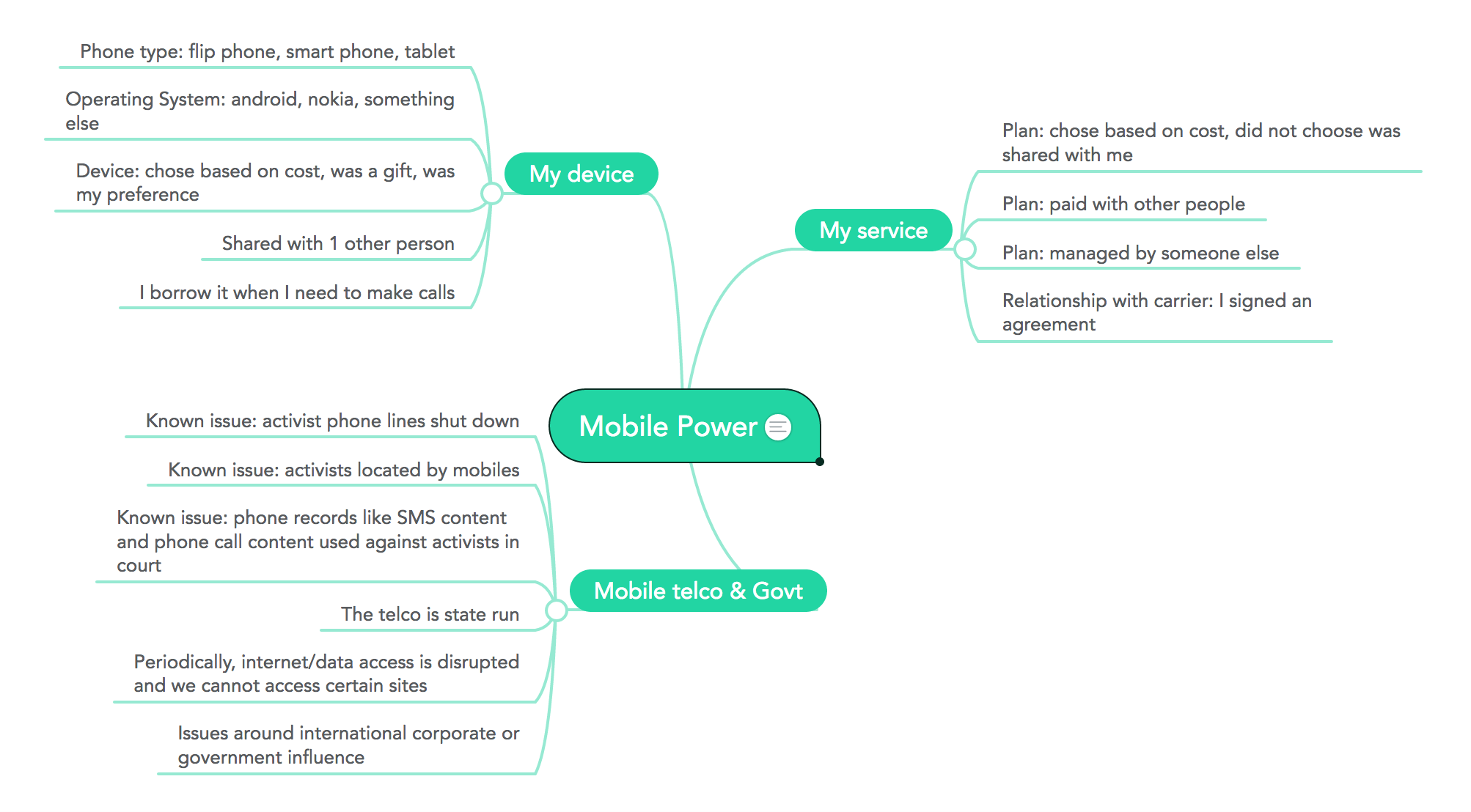

- Mobile power - device, account, service, state, policy [deepening activity]

- What is a phone? How does mobile communication work? [deepening activity]

- Debate: Documentation of violence [deepening activity]

- Planning mobile communications for actions/organising [tactical activity]

- Back it up! Lock it! Delete it! a.k.a. Someone took my mobile: Border crossings, arrests, seizure, theft [tactical activity]

- Discussion, input + hands-on: Choosing mobile apps [tactical activity]

- Using mobiles for documenting violence: Planning and practicing [tactical activity]

- Reboot your online dating safety [tactical activity]

- Safer sexting [tactical activity]

- Feminist principles of the internet

- Introduction, learning objectives, learning activities and further reading

- Introductions of internet love [starter activity]

- Imagining a feminist internet (3 options) [starter activity]

- The internet race [starter activity]

- Women's wall of internet firsts [starter activity]

- How the internet works: The basics [starter activity]

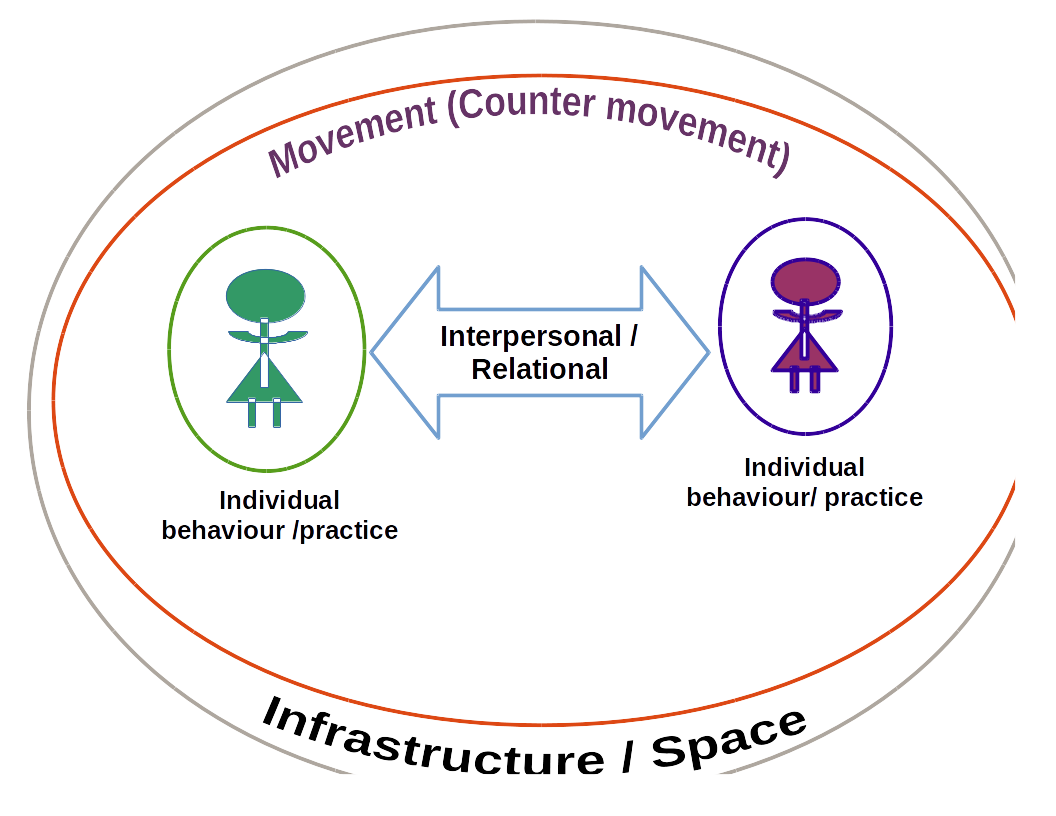

- Social movements: What’s in a tool? What’s in a space? [deepening activity]

- FPI presentation + discussion [deepening activity]

- Risk assessment

- Learning objectives and learning activities

- Introduction to risk assessment [starter activity]

- Assessing communication practices [starter activity]

- Daily pie chart and risk [starter activity]

- The street at night [starter activity]

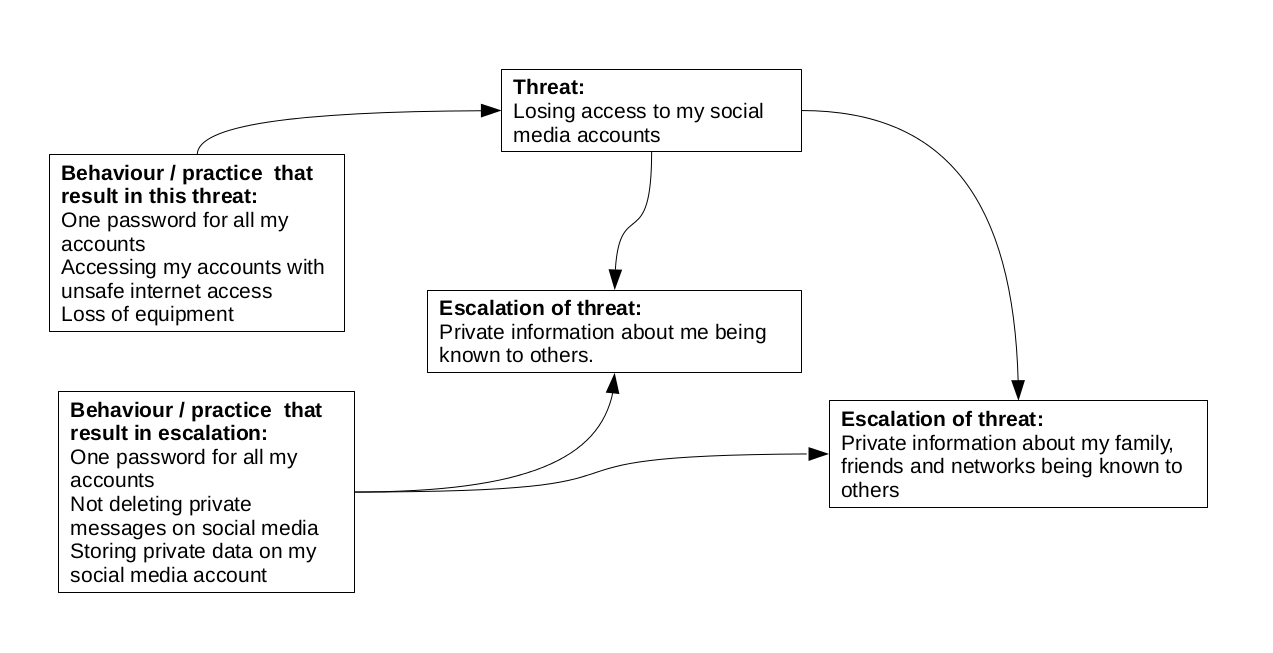

- Re-thinking risk and the five layers of risk [deepening activity]

- The data life cycle as a way to understand risk [deepening activity]

- Organising protests and risk assessment [tactical activity]

- Risk assessment basics [foundational material]

- Risk assessment in movement organising [foundational material]

Introduction

Welcome to the FTX: Safety reboot

The FTX: Safety Reboot is a training curriculum made up of several modules for trainers who work with women’s rights and sexual rights activists to use the internet safely, creatively and strategically.

It is a feminist contribution to the global response to digital security capacity building and enables trainers to work with communities to engage technology with pleasure, creativity and curiosity.

Who is it for?

The FTX: Safety Reboot is for trainers working with women’s rights and sexual rights activists on digital safety. Trainers should be familiar with the obstacles and challenges faced where misogyny, censorship and surveillance are restricting activists’ freedom of expression and ability to share information, create alternative economies, build communities of solidarity and express desires.

Why the FTX: Safety Reboot?

The FTX: Safety Reboot explores how we occupy online spaces, how women are represented, how we can counter discourses and norms that contribute to discrimination and violence. It is about strategies of representation and expression and enabling more women’s rights and sexual rights activists to engage technology with pleasure, creativity and curiosity. It is a feminist contribution to the global response to digital security capacity building, bringing the APC Women’s Rights Programme’s unique methodology and approach, which we call Feminist Tech eXchanges (FTX).

The APC Women’s Rights Programme (APC WRP) has developed the FTX: Safety Reboot as a contribution to existing training guides on digital security but rooted in a feminist approach to technology. The FTX: Safety Reboot is a work in progress to assist trainers to enable activists to use the internet as a transformative public and political space, to claim, construct, and express ourselves more safely.

Our political framing and tool for analysis are the Feminist Principles of the Internet (http://feministinternet.org), which shape and inform our work. The FPIs build our case for a safe, open, diverse and gender-just internet.

What does it do?

FTX creates safe spaces of exchange and experience where the politics and practice of technology are informed by local, concrete and contextual realities of women. These spaces aim to build collective knowledge and ownership. We are conscious of power relations which can be easily set up, particularly around technology, an area where women are historically excluded and their contributions invisibilised. We advocate for change through working towards consciously deconstructing these power relations.

APC WRP capacity-building work bridges the gap between feminist movements and internet rights movements and looks at intersections and strategic opportunities to work together as allies and partners. APC WRP prioritises inter-movement building in order to bridge gaps and grow understanding and solidarity between movements.

What are the FTX core values?

FTX core values are: embedding a politics and practice of self and collective care, participatory and inclusive, secure, fun, grounded in women’s realities, transparent and open, creative and strategic. FTX emphasises the role of women in technology, prioritises appropriate and sustainable technologies, and is framed by the Feminist Principles of the Internet. FTX explores feminist practices and politics of technology and raises awareness on the critical role of communication rights in the struggle to advance women’s rights worldwide. Recognising the historical and current contributions of women in shaping technology, FTX grounds technology in women’s realities and lives. We emphasise local ownership of FTX and have seen the uptake of FTX by our members and partners over the years.

Training modules and getting started

What are the training modules?

The FTX: Safety Reboot currently contains the following five independent modules (with one in draft form) rooted in interactive learning activities to facilitate communities in sharing knowledge and values around representation and expression and to build confidence and skills to be safe and effective in online spaces.

Online gender-based violence |

Creating safe online spaces |

Mobile safety |

Feminist principles of the internet (FPIs) |

Risk assessment |

What do the modules contain?

The modules listed above contain information and resources that can be used independently or in groupings as needed.

Learning Activities

The learning activities in each of the modules have been divided into three kinds:

Starter Activities

Are meant to get the participants to start thinking about a topic and spark discussions. For the trainer/facilitator, these activities can be diagnostic tools to observe what levels of understanding the group has, and to adjust the workshop based on that.

Deepening Activities

Are meant to expand and dig into the topics and themes.

Tactical Activities

Are meant to respond to multiple learning objectives in practical ways. These include hands-on exercises and practical strategising activities.

Getting started

Get to know your participants

Use one of the Training Needs Assessment methods described here to learn more about your participants:

Plan your training

Design your agenda based on what you have learned about your participants, their needs and interests, and suggestions in the Learning Pathways suggested in each module. See also:

Localise your training

Activities reference real life examples and the more you can draw on local examples that are significant to the lives and work of participants, the more participants will be able to engage with the material and learning objectives.

We suggest familiarising yourself with examples that are relevant to your participants and prepare yourself to speak about these. If you are able to engage with participants before the training, ask your participants for significant incidents relating to the workshop you'll be facilitating, and research these more deeply so you understand the cases and can share them in the workshop.

Frame your training

To make your training a safe and inclusive space for discussion, you can refer to useful feminist frameworks/resources such as Intersectionality and Inclusivity and Notes for Holding up a Healthy Conversational Space. You can also refer to our Feminist Practices and Politics of Technology, our Feminist Principles of Participation and the Feminist Principles of the Internet.

Writers and Collaborators

WRITERS

- APC Women’s Rights Programme (APC WRP) - Erika, hvale vale, Jan, Jenny

- Cheekay Cinco

- Bex Hong Hurwitz w/Tiny Gigantic

- Jac SM Kee

- Helen Nyinakiiza

- Radhika Radhakrishnan

- Nadine Moawad

COLLABORATORS

- Bishakha Datta, Point of View

- Christina Lopez, Foundation for Media Alternatives

- Cecilia Maundu

- cynthia el khoury

- Fernanda Shirakawa, Marialab

- Indira Cornelio

- Javie Ssozi

- Nadège

- Nayantara Ranganathan

- Ritu Sharma

- Sandra Ljubinkovic

- Shubha Kayastha, Body and Data

- Smita Vanniyar

- Florie Dumas-Kemp

- Alexandra Argüelles

visit TakeBacktheTech

FTX Safety Reboot Convening

Resources to prepare your training sessions

Get to know your participants

In order to be able to design appropriate and relevant training workshops, it is recommended that trainers/facilitators conduct a Training Needs Analysis with their participants. Through this process, the trainer/facilitator can begin learning about the contexts, the expectations, the technical baselines, and the current understanding of the relationships between feminism and technology of their intended/expected participants.

There are various ways to do this process, depending on the time available, access to participants, and resources on-hand. Here we provide guidelines for three different types of Training Needs Analysis:

- Ideal Training Needs Analysis: There is ample planning and designing time. The trainer/facilitator has access to the participants.

- Realistic Training Needs Analysis: The trainer/facilitator has limited time to plan and design the training workshop, and limited access to participants.

- Base-Level Training Needs Analysis: There is limited time to plan and design the training. The trainer/facilitator has no access to participants.

Note: Conducting a pre-training needs analysis does not mean that the Expectations Check during the first session of the training workshop is no longer necessary. It is advised that any workshop should still include that session to confirm and reaffirm the pre-training needs analysis results.

Ideal training needs analysis

- Preparation time: More than one month

- Comprehensive Training Needs Analysis Questionnaire (Annex 1)

- Baseline Interview Questions (Annex 2)

In this scenario, the trainer/facilitator has ample time to plan and design the training workshop, which means they have the time to connect with the participants, the participants have time to respond, and the trainer/facilitator has time to process the responses.

Given that there is proper lead time for the training planning and design, there are three methodologies in the ideal scenario:

Comprehensive Training Needs Analysis Questionnaire for Participants (see Annex 1 for the questionnaire). In this questionnaire, there are questions about the participants' use of technology and tools, as well as their understanding and knowledge of feminist tech concepts and online GBV, and their expectations for the training workshop. Using this questionnaire, the trainer/facilitator will be able to get a better picture of the needs and realities of the expected participants.

Follow-up Interviews with Participants. Based on the results of the questionnaire, the trainer/facilitator can get a sample of the expected participants to take part in an interview. Ideally, the sample should include all the participants, but a minimum of 50% (depending on the number of participants) should be met. Participants who had outlier/unique responses to specific questions (i.e. the ones with the most experience and the least experience in technology; or the ones with the most knowledge and the least knowledge about feminism and technology; or the ones who have very specific expectations from the training workshop) should be part of the interview process. Usually, these interviews with participants take 60 minutes maximum.

Consultation with Organisers. In this stage, the trainer/facilitator meets with the organisers to share the results of the questionnaire and the interviews, and the proposed training plan and design. Here, the trainer/facilitator also confirms that the design and plan meet the organisers' goals and agenda. It is assumed here that throughout the entire process, the trainer/facilitator has kept in touch with the organisers.

Realistic training needs analysis

- Preparation time: Less than one month

- Use: Comprehensive Training Needs Analysis Questionnaire (Annex 1) OR Baseline Interview Questions (Annex 2)

This scenario is more common. More often than not, a trainer/facilitator has less than one month to plan and design a training workshop due to resource constraints.

Given the time constraints, the trainer/facilitator will need to short-cut the Training Needs Analysis process, and depending on an initial consultation with the organisers, choose between conducting the Comprehensive Training Needs Analysis Questionnaire, or interviewing 50% of the expected participants (see Annex 2 for Baseline Interview Questions).

Base-level training needs analysis

- Preparation time: Less than two weeks

- Use: 10-Question Training Needs Analysis Survey (Annex 3).

In this scenario, the trainer/facilitator has less than two weeks for planning and designing the training workshop. Here, the trainer/facilitator barely has time to get to know the participants before the training workshop and may distribute this questionnaire at the start of a workshop or as participants enter the workshop. While there are a few ways to make up for this lack of pre-training needs analysis during the workshop itself – Expectations Check, or running a Spectrum of Technology Use Exercise, or the Women's Wall of Technology Firsts, we still recommend trying to have the participants respond to a 10-Question Training Needs Analysis Survey (see Annex 3).

Resources

Annex 1: Comprehensive training needs analysis questionnaire for participants

linked here as an .odt document

Annex 2: Baseline interview questions

The purpose of this interview is to short-cut the Comprehensive Training Needs Analysis Questionnaire for Participants. So it will cover the general topics covered by the questionnaire, but with less detail. These interviews are supposed to be 60 minutes long. Each set of questions should roughly take about 10 minutes.

- Tell me about yourself. Your organisation, your role there. Where are you based? Which communities do you work with?

- What are the challenges you face in your work when it comes to using the internet? Is this a challenge that the communities that you work with face as well? In what way? How are you or your community members addressing these challenges?

- What internet applications do you use the most? Do you use them for work or for your personal life?

- Which device do you use the most? What kind of device is it? What operating system does it run on?

- What are your top concerns about using the internet and the applications that you use? Do you feel like those applications are secure?

- Can you tell me what your top three expectations are about the training workshop?

Annex 3: 10-Question training needs analysis

- Name, organisation, position, and description of the work that you do.

- What kind of communities do you work with, and what are their main issues?

- How long have you been using the internet?

- What operating system do you use the most?

- What kind of mobile phone do you have?

- What are the apps that you use the most?

- What are the top three concerns you have about your use of technology and the internet?

- What are the top three security tools/practices/tactics that you use?

- What do you think are the top three issues around feminism and technology?

- What do you want to learn from the training?

Evaluate your training: Training evaluation tools

Why evaluate?

- To do it better next time.

- To design follow-up support for participants around the workshop learning objectives.

Process

+/-/delta This is a simple method for participants and trainers to share input. We suggest doing this at the end of a workshop for single-day workshops, and at the end of each day for multi-day workshops. We suggest simple feedback methods for the end of workshops because people will tend to be fatigued, with attention wandering, by the end of a training period. A method like this can be quick and participants can choose to share details based on their preferences.

Ask each participant to consider and share things they think were good, things that were bad, and things that should change.

Depending on the time available and the resources you have on hand, participants can write their responses on pieces of paper and hand them to the facilitator, or you can go around and get each participant to say their responses out loud while a facilitator writes them down.

After everyone has shared, trainers/facilitators sit together, share their own +/-/delta reflections as facilitators, and review the participants' +/-/delta reflections. You can use these to:

- Create a list of learnings to share with other trainers/facilitators.

- Make adjustments to this and future workshops.

- Design your follow-up with participants.

One-week follow-up Follow up with hosts and participants to share any resources from the trainings you are able to share (facilitation guide, slides, handouts, etc.) and any reflections you may have about the workshop and next steps.

Three-month follow-up Follow up with the hosts and participants to ask about the impact of the workshop. This is a good time to ask people if they have implemented tools and tactics, revisited their own strategies, etc., as a result of your training.

Intersectionality and inclusivity

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live in single-issue lives.” – Audre Lorde

What is intersectionality?

intersectionality is a framework that recognizes the multiple aspects of identity (such as race, caste, gender) that enrich our lives and experiences and that compound and complicate oppressions and marginalizations.

Here is an example to understand intersectionality in context: Between 25% and 50% of women experience gender-based violence in their lifetime. But this aggregated number hides the ways that multiple oppressions compound such violence. Women of color are more likely to experience gender-based violence than White women and wealth privilege can help to insulate some women from some forms of violence. Bisexual women are far more likely to experience sexual violence than other women. Transgender people are also more likely to experience hate violence than cisgender people. In short, all women may be at risk for gendered violence, but some women are far more at risk.

How do I practice intersectionality in conversations?

Those of us with identity privilege (example: white, straight, cis, able-bodied identities) can have a harder time including those who are oppressed in our feminism. That is why it is important to focus on creating inclusive, respectful spaces where the lived experiences of all women are valued and understood. Here are 5 quick pointers you can keep in mind to create intersectional and inclusive conversations.

- Self-reflect and recognize your privileges: Taking up the difficult work of investigating our own privilege is key to intersectional feminism. It is a good practice to look within ourselves and take upon the desire to learn about issues and identities that do not impact us personally. Being privileged doesn't necessarily imply that our existence oppresses another community. What it means is there are certain experiences we don't have to go through because of who we are.

- Decenter your perspective: It’s important to understand that feminism is about more than ending sexism — it’s also about ending all the interconnected systems of oppression that affect different women in different ways. There are things that our privileges allow us to take for granted - able bodied people don’t always notice ableism, and White people don’t always notice racism. So make an effort to avoid centering feminism around yourself or people of privilege.

- Listen to each other: On the feminist issues where we hold privilege, it's crucial to listen to the experiences of all women, including those women who don't to see the world through a more inclusive lens You can't walk the walk if you don’t know where the walk goes. So if you are a White feminist, be mindful that you are not talking over or for people of color.

- Think about the language you use: If you are a non-Muslim feminism, be wary of saying things like “It must feel hot outside in a veil”. Using terms such as #PussyPower can alienate transgender women who may not possess these body parts. These are two examples of the many ways in which the language we use can ostracize women. It is good practice to constantly check ourselves and how we talk about women who do not look like us, or who lead lives different from our own.

- Be willing to make mistakes and correct for them: Adopting an intersectional framework is not an easy process. So, sometimes despite our best efforts at being inclusive, we may slip up and get called out for our mistakes. Rather than becoming defensive, recognize that being called out is not really about your worth as a person, and that you can apologize and adjust your behavior to avoid repeating the same mistake.

- Recognize that everyone brings knowledge to the table: Recognizing that everyone brings knowledge to the table helps to lessen the distance between us and challenge the idea that some of us know more than others when really we all know some things more than others. Working together to learn from each other (as the activities in these modules are designed to achieve) helps everyone gain most from this experience.

Additional resources

- https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/01/why-our-feminism-must-be-intersectional/

- https://www.bustle.com/articles/117968-5-reasons-intersectionality-matters-because-feminism-cannot-be-inclusive-without-it

- https://www.elitedaily.com/women/feminism-inclusive-women/1507285

Notes for holding up a healthy conversational space

A conversation on gender-based violence can evoke different responses from different individuals based on their personal experiences and privileges. Here are a few pointers to keep in mind while talking about this sensitive issue.

1. All participants do not have the same level of privilege

While the included modules offer many activities and resources, many discussions are not just intellectual exercises for everyone ― people who face discrimination or have experienced violence are potentially dealing with a mental health issue.

2. Importance of trigger warnings

Trigger Warnings allow those who are sensitive to the subject of discrimination and violence to prepare themselves for discussing about them, and better manage their reactions. Remember, the key to an effective Trigger Warning is being specific - if a Trigger Warning is not specific enough, it could refer to anything from eating disorders to bullying. Thus, it’s a good idea to follow Trigger Warnings with specialized lists of content. For example, while discussing a case study on partner violence, you could specify beforehand, “A quick heads-up: This discussion contains instances of Rape, Abuse, and Partner Violence. If you feel triggered, please know there are resources to help you.”. For those who need the warning, this helps them prepare for the discussion, and for others, this helps sensitize them to the fact that those around them can find the discussion hard going.

3. Do not pressurize someone to talk about their experiences

Forcing someone to talk about a sensitive event is making someone re-live the experience and all of the negative emotions that come with it. Some people just aren’t ready to open that box of worms. Instead, give people room to explore the trauma and the the time to open up when they are ready.

How to help someone who feels triggered

Even with the best of preparations, sometimes precautions don’t work because triggers are usually individual specific. Here are a few steps you can take to help someone who feels triggered by an ongoing discussion.

1. Recognize

Recognize that your content could be hurtful to someone.

2. Apologize

Apologize for saying something that hurt the person. Remember that the apology is about the person who has been hurt, and not about you. Avoid justifying or defending your words or actions and be sincere about your apology; it is not personal.

3. Empathize

Empathize by trying to understand why the person may be hurt. You can do this by actively listening to the person who is feeling triggered.

4. Rectify

Continue the discussion by avoiding a repetition of the said trigger. Remember that triggered reactions can temporarily render people unable to focus, regardless of their desire or determination to do so. Be open to participants leaving the conversation if they feel uncomfortable. Make sure they have access to help if they need it. It is advisable to have a mental health professional on board for such emergencies at events.

If a professional is not present at the venue, here are a few resources that can enable you to help someone who’s been triggered:

- https://www.rainn.org/articles/flashbacks

- https://www.bustle.com/articles/87947-11-ways-to-help-a-friend-whos-been-triggered-because-it-is-most-definitely-a-real

Feminist practices and politics of technology

FPT embodies both a critical perspective and analysis of technology. It poses questions and defines issues relating to technology from feminist perspectives, taking into account various women's realities, women's relationships with technologies, women's participation in technology development and policy-making, power dynamics in technologies and feminist analysis of the social effects of technologies.

FPT defines our approach to training. It defines the core values that comprise feminist technology training. It is based on the experiences of women and feminists in and with technology training.

FPT is a growing idea. How it has been defined so far can change and mutate through practice, discourse and experience, and because politics and contexts change.

FPT recognises and advocates that feminist practices of technology cannot be devoid of a feminist perspective and analysis of the politics of technology.

FPT views technologies in two ways: on one hand, technology has resulted in new issues for women and in new permutations of women's issues; on the other hand, technology provides new solutions and approaches to addressing women's issues. It grounds new technologies to women's issues, interrogating how women's realities influence how technologies are developed, used, appropriated and benefitted from as well as how technologies are changing women's realities. It also looks at technologies with a strategic and creative eye, assessing how they can be developed and appropriated to support and facilitate women's rights agendas.

As a perspective, it does not define what the conclusions and issues are. Rather, it poses questions and issues that would lead to exploring and interrogating technologies from feminist perspectives.

Some of the questions include:

- How has user-generated content (as facilitated by the internet) changed women's representation in media?

- What are the new ways of and spaces for women's building on the internet?

- How have women's issues changed as a result of our increasingly technology-driven cultures?

- Is online communications secure for women?

- Who controls technologies?

- How can women's rights activists benefit from new technologies?

- What does 'control over technology' mean?

As an approach to training, FPT has core values that define 'feminist technology training'. It springs from the experiences of the FTX trainers as participants and facilitators of technology training. Most of these reflect the values that have already defined 'feminist training'. The difference is that these values are specifically relevant to technology training contexts.

The core values include:

Participatory / Inclusive

Feminist training recognises that the trainer has as much to learn from the learners as they do from her and from the other learners. As such, training will be designed in such a way that will facilitate exchange and discussion.

Feminist training allows for various ways of learning and communicating to accommodate different learning styles.

Feminist training allows for differences in opinions, in experiences and in contexts. It does not assume that all of the participants come from the same background, and it has to be flexible enough to accommodate differences.

Secure

Feminist training is a space where the participant feel safe in two ways: in their learning – that they can ask questions, raise issues, divulge information that will not be rejected, belittled and divulged without their consent in their understanding of technologies – that they are aware of the (possible) risks of certain technologies (i,e. Privacy in social networking sites, safety in using the internet to publish alternative content, etc.)

Grounded in women's realities

Feminist training should be based on the needs and realities of the participants. This means, that technologies that will be tackled will have to be appropriate and relevant to the participants. This also means that discussions on technologies must take into account the context of the participants.

Appropriate / sustainable technologies

Feminist training should prioritise technologies that the participants can apply, appropriate and use after the training for their work.

Free and Open Source software will be given priority, but only if the participants can sustain their use post-training.

Transparent / open

Feminist trainers are aware of that they have their own agenda for the training and they make their goals apparent to their participants. This means having processes where expectations from participants and trainers are negotiated and agreed upon.

Creative / strategic

Feminist training is an opportunity to look at technologies strategically and creatively to appropriate them in ways that are relevant to the participants' contexts.

Emphasising the role of women in technology

Feminist training highlights women's contribution to technology development, use and policymaking. Women like Ada Lovelace and others who have significantly contributed to technologies are great role models, specifically for learners who have fears regarding technologies.

Furthermore, this contributes to correcting the mis-representation of women in the history of technology.

Emphasising women's control of technology

Feminist training is not afraid to get into the deeper aspects of technologies (in development and in policy-making) and emphasis on 'control' and full understanding of how technologies work (and not just on use) must be made.

Fun!

Feminist training should be a space where women can have fun with technology to break down barriers that affect women's relationships and control over technologies.

Our feminist principles of participation

This document has been developed by WRP APC as a guide for ourselves and partners hosting learning and capacity building events, such as Take Back the Tech campaigns, Feminist Tech Exchanges and conversations around the Feminist Principles of the Internet. You can find a pdf version here.

We have produced this in a spirit of collaboration and co-ownership to encourage creating spaces both online and onground, that are framed as feminist and facilitate safety and fun for all as well as promoting and upholding principles of diversity, creativity, inclusivity and pleasure. We come from many communities, cultures and faiths and embody a beautiful diversity of physical, social and psychic realities. Through creating safe, fun and caring spaces, we enable engaged participation, deeper learning and the possibility of growing dynamic, responsive and caring movements.

These are the framing principles we value and apply in the spaces and events we co-create.

- Create a safe space for all participants.

- Be respectful.

- Be collaborative and participatory.

- Recognise and value diversity.

- Respect the privacy of participants.

- Be aware of language diversity.

- Handle disagreement constructively.

- Embed politics and practice of self and collective care

The principles in action

Create a safe space for all participants.

As far as possible, for example through an online survey, get to know your participants beforehand. Ask for specific needs they might have such as physical access, dietary requirements, particular travel fears or safety requirements. Ideally the venue should have light and air, be quiet and be free from surveillance and interference from non-participants. During the event, gently encourage participants to be open about subjects which might cause them distress and to take responsibility for alerting facilitators if they feel uncomfortable.

Be respectful.

Negotiate with participants at the start of the event about what is needed for a respectful and nurturing environment. Encourage deep listening – meaning that we give our full attention to each other. Acknowledge that there are things that our privileges allow us to take for granted – for example, able bodied people don’t always notice ableism, white people don’t always notice racism.

Be collaborative and participatory.

As trainers/facilitators be well prepared, open and aware of your own agenda for the event and make your goals apparent to the participants. Have processes where expectations from participants and trainers are negotiation and agreed upon -- for example, use smaller groups if some people are not comfortable speaking in plenary. Ground learning in women’s lived realities and use methodologies that prioritise participant voices and experiences. Recognise that everyone brings learnings to the table.

Recognise and value diversity.

Acknowledge differing levels of privilege in the room as well as our multiple identities. Ensure that intersectionality does not make people feel more excluded and ‘different but encourages the harnessing of diversity of identities and experiences as an opportunity for learning, exchange and enriching the space. Help people recognise that a discussion on ableism or racism is not necessarily targeting the able bodied or white people in the room as perpetrators of discrimination and encourage people to listen, think and explore systemic discrimination.

Respect the privacy of participants.

Ask for consent on photographs and directly quoting participants / giving attribution for documentation. Agree on the use (or not!) of social media. Co-develop a privacy agreement for the event. If there are discussions on sensitive issues such gender-based violence, racism, homophobia or transphobia, recognise that some participants may not be ready to speak about these things. Do not push discussion about personal experiences if this causes distress. Always ensure there is a trained person available to support participants who have experienced trauma.

Be aware of language use and respect language diversity.

Acknowledge the languages of all participants and as far as possible offer interpretation/translation. As a rule, everyone should speak clearly and slowly, and feel comfortable asking about acronyms or terms that are not understood. Ask that people think about the language they use and not to use terms that might be oppressive or offensive to others. Request that people be open if they feel offended and use these as learning opportunities. Content may involve technological terms or language that is considered academic and that could be new to some participants. Challenge the tyranny of technological terms! Make content understandable and intriguing and emphasise taking control of and growing a full understanding of how technologies actually work.

Handle disagreement constructively.

Act fairly, honestly and in good faith with other participants. Encourage empathy and take the time to rectify any disagreements, any uncomfortable or hurtful words or behaviour that may occur. Create an atmosphere of openness and facilitate space for apologies and/or explanation if needed.

Embed politics and practice of self and collective care.

Acknowledge that self-care is different for different people and depends on who we are and where we are located in our lives and contexts. Self-care and collective care impact each other. So make time for people to breathe, connect with bodies and hearts, through ritual or embodied practice, to release any tension or anxiety. As holders of space, be mindful of and try and clear any stress in the room so that people can show up to the collective and participate fully. Invite participants to suggest self-care practices.

We encourage people to read APC’s Sexual Harassment Policy can be found here: APC_Sexual_Harassment_Policy_v5.1_June_2016.pdf

FTX Safety reboot convening 2018 draft agenda

Overall design and activities

Goals of the convening

- Bring together feminist practitioners and trainers working on digital safety and self-care to unpack, understand, apply, adapt, contextualise and deepen the FTX: Safety Reboot curriculum on feminist digital security which APC WRP is building.

- Create a space for skill and knowledge sharing on methodologies, approaches and pedagogies for building confidence, growing knowledge and uptake in this area by women's rights and feminist activists in different movements.

- Integrate feminist work on the politics of care and well-being into the field of digital security and promote and support political kinship, solidarity and a deepened understanding of the feminist practice of technology.

- Facilitate building a trusted network of feminist trainers and facilitators for collaborative work, continued exchange and active solidarity in this area.

Day 1: Grounding ourselves and our work

The first day will be about talking about rooting the convening on three levels:

- the context that brought everyone together: WRP´s work, FTX safety reboot, the plans for a feminist commons, etc

- the world that we live in and do our holistic security work: discussion of issues that we face, and that our participants face

- what it means to be a feminist trainer

Proposed activities

- Participant intros and agenda setting (This might happen on two levels: one with the participants from the FTX Convening and the TBTT Global Meet-up, and again in the FTX space.)

- Part of the morning will be merged with the TBTT Meet-up

- Grounding ourselves holistically [title pending] (session to be led by Sandra and Cynthia)

- Visualising where we work in, who we work with and who we are as trainers

- A session on the world in which online gender-based violence happens (merged with the TBTT folks)

Day 2: Challenging ourselves

The second day will be mostly about having facilitated sessions about the challenges we face as trainers, and different ways of doing the training work that we do. These suggestions are largely based on the responses to the survey that we sent to the participants. We can accommodate about 5, 1.5 sessions for this day.

- Integrating well-being and self-care in our work (to be led by Sandra and Cynthia)

- Digital Security At The Grassroots (Bishakha volunteered to lead this)

- Organisational security (co-facilitated by Bex and Dhyta)

- [Late afternoon] Fish bowl session on risk assessment (convergence with the TBTT Meet-up)

Other possible topics.

- Re-imagining how we train (storytelling, the use of art, avoiding fear-based tactics, not using military language, etc)

- Re-imagining risk assessment

- Countering online gender-based violence

Day 3: Exploring ways forward

This day will do focused work on the FTX modules. At the end of Day 2, it would be good to have teams of people who are looking at the parts of the FTX Safety Reboot that they want to work on more.

On Day 3, we give them time to look at the parts and to reflect on the following questions:

- How will this module be useful in your context? How would you change it? What would you add?

- What are the points in the module that will cause your participants stress? And how will you address that?

- What do you need as a trainer - facilitator to be able to apply this module? Skills, knowledge, experience, prep work?

And in their teams, they can discuss suggestions for improvement.

(I really want to have time for folks to try out activities with each other, and perhaps with the TBTT folks. But that would take time. So any ideas around how we can do that would be welcome.)

Day 4: Working together?

For this day, maybe leftover work from Day 3. But also, have conversations about:

- sustaining ourselves as trainers

- the feminist commons

- how we work together in the future, opportunities for collaboration

- what happens to the FTX modules

We will also be interfacing with the TBTT folks towards the end.

Visualising where we work in, who we work with and who we are as trainers

Activity 1

Here, we ask the participants to draw one our two typical folks that they work with in their trainings, with focus on the following parts:

- Head: what do they know, what issues do they grapple with

- Heart: what is important to them, what do they value, what do they believe in, what are their fears

- Hands: what are the skills they have, what do they bring to the training

- Feet: where are they? what contexts do they live in

This activity will allow for time for self-reflection, but the processing will happen in small group discussions.

Here, we aim to begin to start grounding the work in the realities and contexts of the people that our participants work with.

Activity 2

Using the same method as above, ask the participants to draw themselves.

Give them time to reflect on the the drawings that they have done.

Activity 3

In small groups, have time for to discuss the following questions:

- What are the threats our communities are facing? How has it changed?

- As activists and part of social movements, how does our work as trainers contribute to the cause?

- What are the limitations of training as an intervention? Are there other capacity development modes we should be exploring?

- What are the gaps between who we are as trainers and who the folks we work with?

- Given the activities, what does it mean to be a feminist trainer?

Debrief

Then we come back to the big group and have a discussion about what the groups talked about.

Online gender-based violence

Guide participants through the issues relating to online gender-based violence – its root causes, how violence plays out on the internet, the continuum of violence that women, women-identified and queer identities experience online and offline, and its impact. We **highly recommend** that you choose a Learning Path to travel, as these include activities with different levels of depth that should help participants obtain more insight into the covered subjects.

Introduction and learning objectives

Introduction

This module is about guiding participants through the issues relating to online gender-based violence – its root causes, how violence plays out on the internet, the continuum of violence that women, women-identified and queer identities experience online and offline, and its impact.

This module is based largely on the more than a decade of work that the APC Women´s Rights Programme (WRP) has done through the Take Back the Tech! campaign, the End violence: Women's rights and safety online project, MDG3: Take Back the Tech! to end violence against women project, and EROTICS (Exploratory Research on Sexuality and the Internet).

Learning objectives

By the end of this module, the participants will have:

- An understanding of the forms of online gender-based violence (online GBV) and its impacts on the survivors and their communities.

- An understanding of the continuum of violence between the offline and the online spheres, and the power structures that allow it.

- Ideas, strategies and actions about the ways in which online GBV, especially in their contexts, can be addressed.

Learning activities and learning paths

This page will guide you through the Module's correct use and understanding. Following the Learning Paths, with activities of varying depth, should allow participants to obtain a better grasp of the studied subjects.

Learning paths

How you can use the activities below – and combine them – will depend on:

- the purpose of your workshop (are you raising awareneness or are you expecting to come up with strategies to respond to online GBV?);

- your participants (are they survivors on online GBV? Or is their experience more removed?);

- your own experience in facilitating these kind of workshops (are you a seasoned digital storytelling facilitator? A digital security trainer who is now getting into online GBV? Or a campaigner who is expected to run an online GBV workshop as one of your campaign´s activities?);

- the time you have available to you to run a workshop

These learning paths are recommendations for how you can mix and match the activities in this module to create a workshop on Online GBV.

We recommend beginning with Online GBV or not? to spark discussion, surface shared understandings of online GBV, and clarify key concepts. This activity would work if your workshop is more general awareness-raising.

Following that, depending on time and the context, you can work with participants using the Deconstructing online GBV or Story circle activities to deepen the group's understanding of online GBV, and to ground the conversation in experiences of people in the room (Story Circle) or case studies (Deconstructing Online GBV). Both deepening activities may cause participants distress, they require preparation.

For the Story Circle activity, specifically, facilitation will need a lot of care and consideration. We do not recommend this activity for solo facilitators, and for those who are just beginning to do these kinds of workshops.

There are Tactical activities that are meant for strategising on response to online GBV. The Take Back the Tech! Game focuses on general approaches to addressing online GBV. If you have limited time, the tactical activity: Meme this! is shorter and faster. It could also be a light activity after a heavy one like the Story Circle on Online GBV. Planning response to online GBV activity aimed towards coming up with a more comprehensive response strategy to specific incidents.

The activity Mapping digital safety could be a standalone workshop with a focus on framing Online GBV with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Some suggested combinations:

| If you have half a day for your workshop, then Online GBV or not? followed by Meme this! |

| If your workshop is focused on strategising and you have limited time, we recommend jumping straight into the Take Back the Tech! Game. |

| If your workshop is about having a comprehensive response to online GBV incidents, then we suggest doing the Deconstructing online GBV, followed the Tactical Activity: Planning response to online GBV. |

Learning activities

Starter activities

Deepening activities

Tactical activities

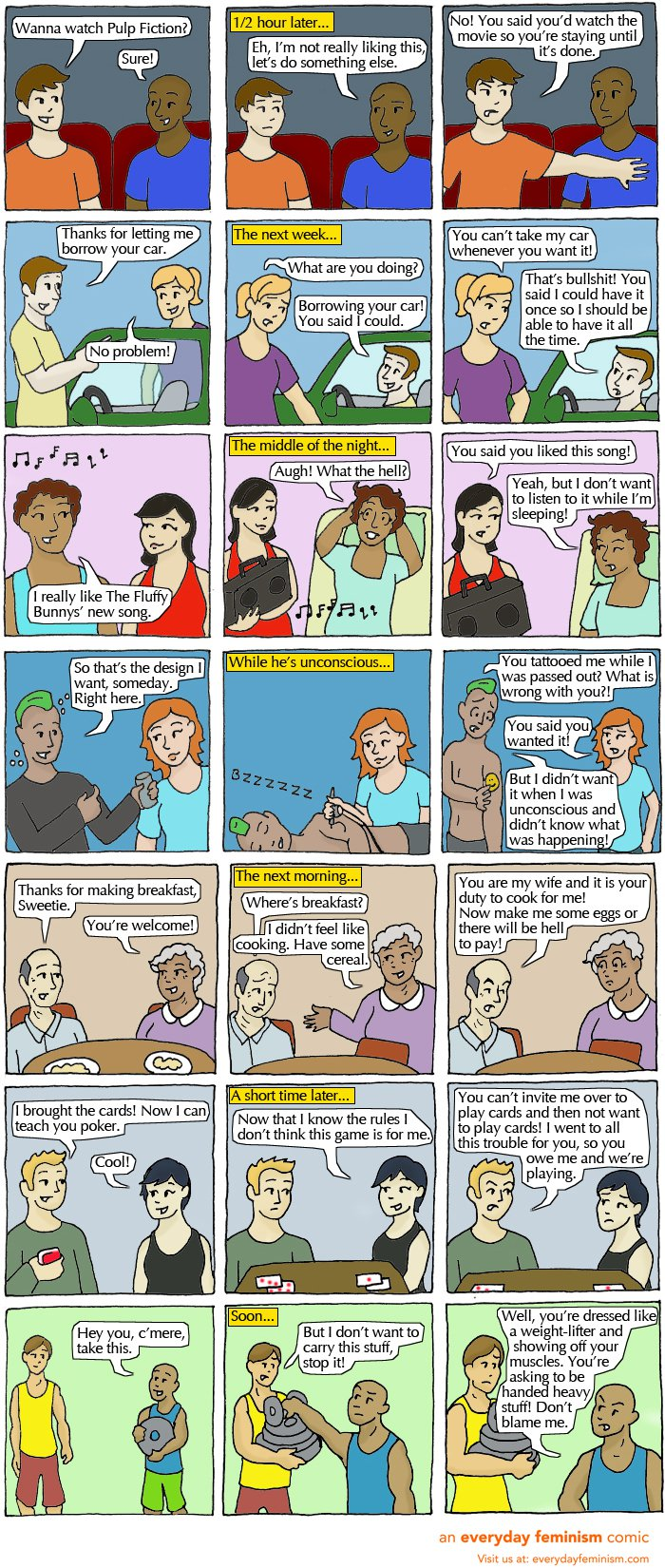

Online GBV or not? [starter activity]

This activity is designed to spark debate and discussion, and give you, the trainer/facilitator an opportunity to clarify concepts relating to the experiences of women and gender diverse individuals on the internet and online gender-based violence (online GBV).

About this learning activity

This activity is designed to spark debate and discussion, and give you, the trainer/facilitator an opportunity to clarify concepts relating to the experiences of women and gender diverse individuals on the internet and online gender-based violence (online GBV). This is specifically aimed towards speaking about the less obvious forms of online GBV, and to discuss the participants' assumptions on how they define what GBV is.

The main methodology in this activity is to show examples of experiences of women and gender diverse individuals online (It would be good to have exagerrated examples to encourage debate or discussion) and memes, and have the participants react with online GBV or Not GBV upon reading/hearing/seeing the example meme. Then you can ask the participants to defend their initial position through a set of guide questions.

It is essential to frame this activity as a vacuum where ALL opinions and viewpoints are allowed (as long as they are expressed in a manner acceptable to the group, assuming Participant Guidelines are established earlier in the workshop), and that what the participants say during this activity will not be quoted/publicised/shared with others. It also a good idea, especially if the group has a lot of experienced feminists, to encourage others to play Devil's Advocate in order to enrich the discussion.

Facilitation Note: It would be ideal to have established and negotiated participant guidelines about respect before-hand, just in case the debate gets heated.

For the trainer/moderator, this activity can be used to learn more about the participants' level of understanding and appreciation of online GBV.

Learning objectives this activity responds to

- An understanding of the forms of online GBV and its impacts on the survivors and their communities.

- An understanding of the continuum of violence between the offline and the online spheres, and the power structures that allow it.

Who is this activity for?

Ideally, this activity is for participants who have an understanding of internet rights, sexual rights and WHRDs.

Time required

Depending on how many examples are shown, this activity can take from 30 minutes to 90 minutes.

Resources needed for this activity

- Signs (not bigger than half a 4A sheet of paper) with Online GBV printed on one side and Not Online GBV! printed on the other. One per participant.

- A way to present the examples of women's experiences on the internet. It could be a poster of the printed memes or a projector to show the memes.

(See Resources for sample memes)

Mechanics

Show a meme or example of an experience that women and gender diverse individuals have had online.

Tip: Perhaps start with a glaringly obvious example of online GBV, then move to more nuanced examples.

After each example, you ask: Is this Online GBV or Not Online GBV?

The participants then raise their boards to show which they chose.

Once everyone has made a choice, you can then ask: Why do you consider this Not Online GBV/Online GBV? Then get an opinion from someone who had the opposite opinion, and allow the group to ask each other questions.

If there is not much disagreement among the group, then dig deep into the example through these guide questions:

- Who is being attacked in this meme? How will it impact them?

- What are the values underpinning this meme? What is the meme creator (and anyone who shares and likes this meme) really saying about women, women-identified, and/or queer individuals, and their communities?

- Does this meme reflect the values in your communities? How so?

- If you had come across this meme, how would you have reacted? How do you think we should react to it?

You can end the discussion with a bit of synthesis, and then move on to the next example.

To synthesise each example, the trainer/facilitator can:

- Do a quick summary of the discussion that the participants had over the example.

- Name what the example is, or the various ways the example has been described.

- Point out the gender stereotyping, gender bias and/or misogyny that was reflected in the meme.

Intersectionality Note: It is also important to draw out how women and gender diverse individuals and communities would be impacted differently by the messages / memes.

You don´t have to do a synthesis for each example that you show. If a discussion on a specific example is similar to a previous one, then you can just point out the similarity.

Facilitation Note: It is important, while the activity is still happening, that you, as the trainer / facilitator, do not take a side in the discussion that the participants are having. Having a facilitator siding with a group of participants is an effective silencer of discussion and debate.

At the end of the entire exercise, you then do a bigger synthesis of the activity. In this synthesis, you can go back to the examples that got the most debate and discussion from the participants, summarise the discussion, and then share your own thoughts and opinions on the matter.

Key points to raise in the main synthesis:

- The relationship between "real world" values and the creation of such memes.

- The existing power structures, patriarchal values, gender bias and bigotry that are showcased in the examples.

- What constitutes gender-based violence.

- How positionality and privilege within the different women and gender diverse sectors have different effects on indviduals and communities.

Facilitator preparation notes

From the start, you need to decide if you are playing a trainer (one with the knowledge and experience to provide answers), or a facilitator (one who guides discussions, and keeps herself from sharing her own opinion) in this learning activity. Being both will not be conducive to a good discussion or a safe space for the participants. If you are being a facilitator, you wouldn't want to provide answers at the end of the discussion, and make participants defensive. If you are being a trainer, you wouldn't want to be so strict in your opinion on the matter that it silences the participants.

Another thing to prepare for is your own assumptions about what online GBV is. Take a refresher by reading Good Questions on Technology-related Violence.

Facilitation Note: This activity is not just to show examples of obvious cases of gender-based online violence, but to have a discussion with the participants about a nuanced understanding of what is online violence and what is not. So, in the examples, include examples of common experiences that women and gender diverse individuals have on the internet – and not just the ones that are glaringly violent.

There are sample Sample Memes found below, but it would be ideal to use examples that are context-specific to the participants in the workshop. It would be good to show a range of examples, including messages or memes:

- that are misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic

- that attack women and gender diverse individuals and communities for their actions

- that name or target specific women or gender diverse individual in the message / meme

- that are overtly-violent and / or calls for gender-based violence

- that represent women and queer bodies as sex objects

- that show offline actions against women put online

- that attack women and gender diverse individuals on the basis of their social class

The point here is to not be too obvious in your sample choices but to generate a discussion among the participants.

If you have time to prepare with the participants, ask them for examples of online harassment that they have witnessed (not necessarily targeted towards them) online, and show those examples in the activity.

Additional resources

Sample Memes

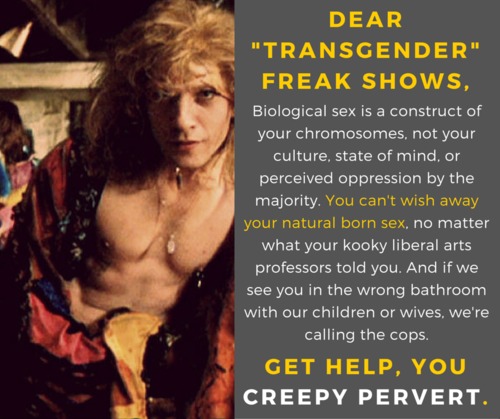

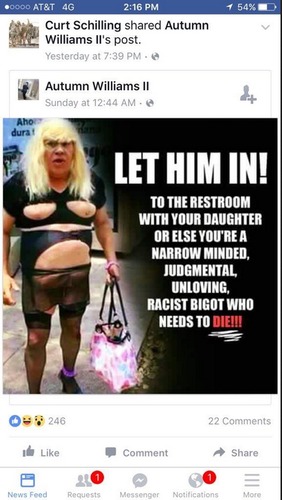

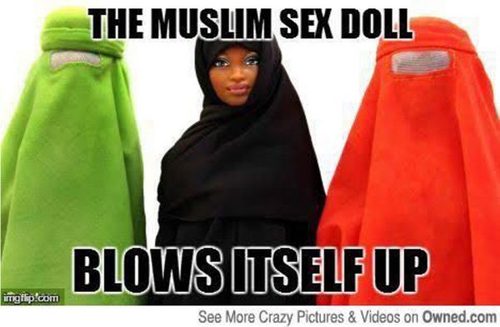

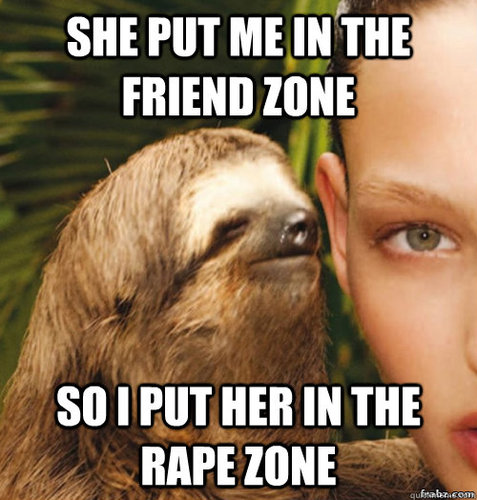

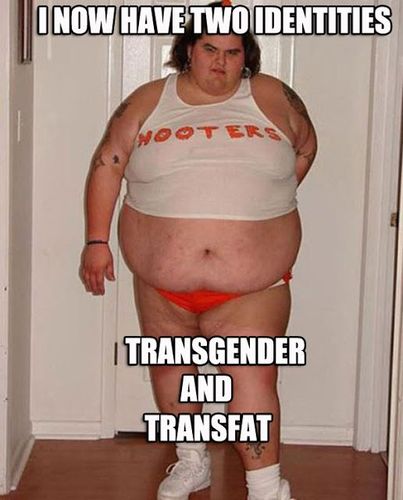

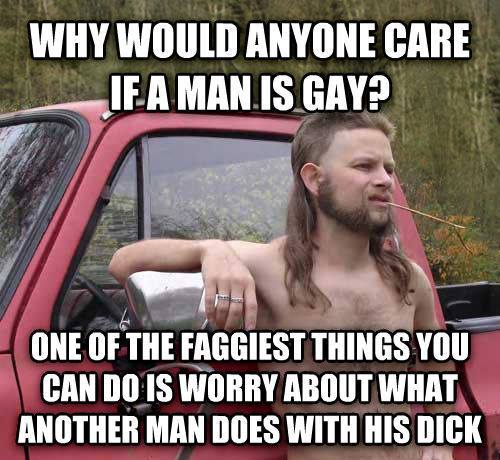

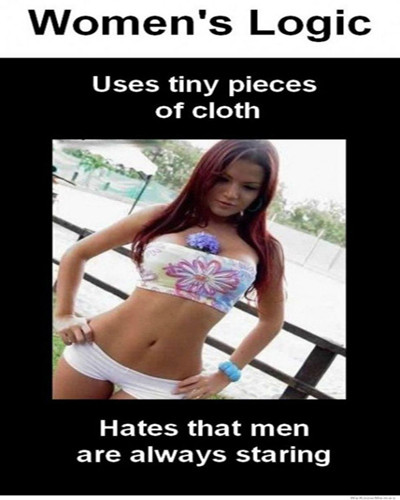

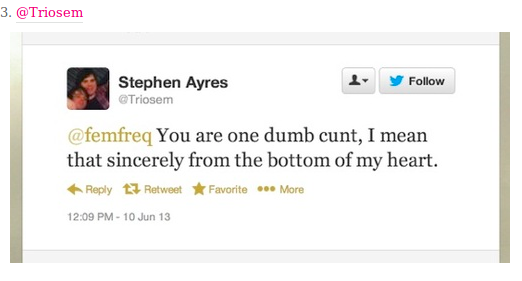

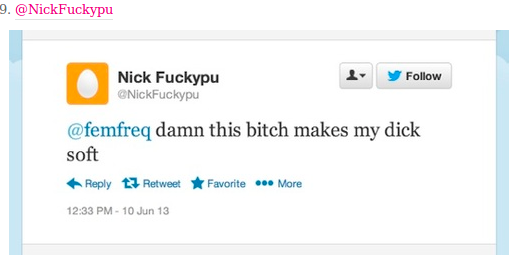

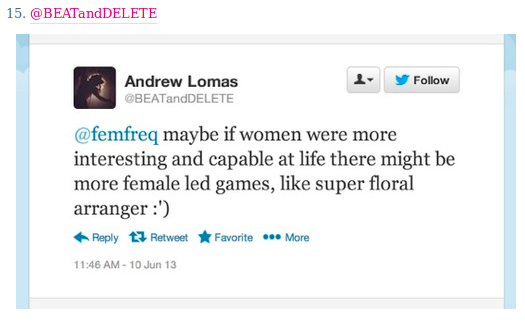

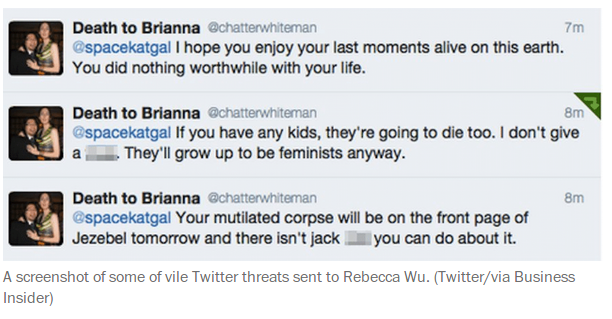

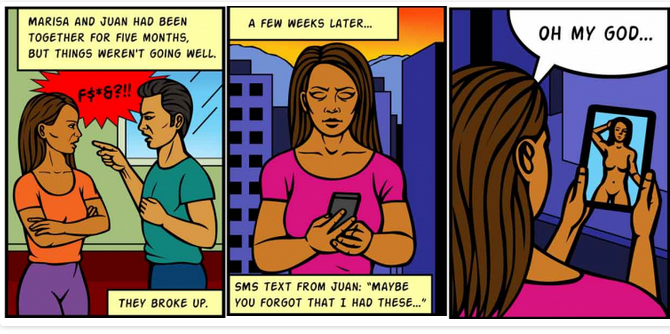

Warning : This page contains racist, sexist, homophobic transphobic and rape apology material.

Facilitators Note: There are sample Sample Memes found below, but it would be ideal to use examples that are context-specific to the participants in the workshop. We encourage you as trainers to find your own memes so that they are relevant to the participants.

Intersectionality Note: In choosing sample memes, make sure that you include different race, class, religious backgrounds, sexual orientation and gender identities.

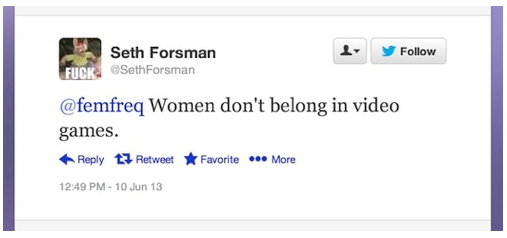

When a woman complains about the lack of women´s representation in video games, a sampling of the reactions she gets:

Deconstructing online GBV [deepening activity]

This activity takes the participants through a case study of an incident of online gender-based violence, and gets them to discuss the different aspects of the case study.

About this learning activity

This activity takes the participants through a case study of an incident of online gender-based violence, and gets them to discuss the different aspects of the case study.

Learning objectives this activity responds to

- An understanding of the forms of online gender-based violence (online GBV) and its impacts on the survivors and their communities.

- An understanding of the continuum of violence between the offline and the online spheres, and the power structures that allow it.

- Ideas, strategies and actions about the ways in which online GBV, especially in their contexts, can be addressed.

An important note, while this session will touch upon ideas for response, the main purpose of this activity will be to unpack an example of an online GBV incident.

Care Note: Unpacking a case study of an online GBV incident might cause participants distress.

This is not an activity to do when you do not know your participants and / or if you have not previously gained trust from the group.

In order to do this more responsibly, it is important that you are aware of the experiences of violence that your participants have (see more here: Get to know your participants), and to be observant as you run this activity about how the participants are reacting.

Encourage your participants to raise their hands if they need a break from the activity.

Knowing and having some experience in some debriefing exercises such as those found in the Capacitar Emergency Kit would be useful.

Who is this activity for?

This activity can be used with participants with different levels of experience in women's rights and technology.

Depending on the level of experience of the participants on the various aspects on relating to online GBV, the trainer / facilitator will need to prepare to intervene to clarify concepts around social media, the internet, and even national laws.

Time required

About 2 hours per case study

Resources needed for this activity

- Flip chart paper/whiteboard

- Markers

- Index cards to write down different aspects of the case study that need to be stressed.

Alternatively, you can prepare slides with the case studies and the questions.

Mechanics

You begin by describing the incident to be deconstructed, writing down the following details on individual index cards and posting them on a wall (or if you have prepared a presentation, these could be the bullet points in your slides):

- Name of the survivor + gender + social class + race + educational attainment + any other identity markers

- Country where the survivor is from + if there are laws that could protect them

- The initial incident of online violence , in which platform did this happen

- Where the incident happened , in which platform did it start

- If you can, name of the initial aggressor/s + some details, if it's important in the case study

- If the aggressor/s cannot be named, write down some details about them: their online handles, etc.

- Relationship between the survivor and aggressor, if any

Then open it up for discussion by asking the participants the following questions:

- Who else should be responsible here aside from the perpetrator?

- Who is the community around the survivor? How do you think they could have responded?

- What are the survivor's possible responses to the situation?

- How do you think this incident affected them? (impact)

Write down the responses on individual index cards and post them on the wall.

Then divulge more details of the case study, marking details that the participants have already guessed and writing down more details on individual index cards:

- How did the case escalate? In which spaces was the violence replicated?

- How did the case spill into the survivor's life outside online spaces?

- How did the community respond?

- What other spaces reinforced the initial incident of violence?

- Who else got involved?

Then open the discussion up again by asking the following questions:

- What recourse does the survivor have?

- What laws can protect them in their country?

- What other impact will this have on the survivor based on where they are from, what they do, what social class they belong to, what country they are in?

- What should happen to the initial aggressor/s? Who can make that happen?

- What should happen to the other aggressor/s, including the ones that extended and escalated the incident?

- What is the responsibility of those who own and run the platform where the incident happened?

- Who else is responsible in this scenario? What is their responsibility?

- How could the women's rights movements respond to this?

Write down the responses of the participants to each question on individual index cards and post them on the wall.

At the end of this, there will be a gallery on the wall that shows the different aspects to the case study of online GBV.

To synthesise, reinforce the following:

- The connection and continuum between online and offline violence.

- The complexity on online GBV: the varied stakeholders, both negative and positive.

- The systems and structures that facilitate online GBV as well as those that might be avenues for redress and mitigation.

Facilitator preparation notes

In order to create a relevant case study that will encourage discussion and understanding of the complexity of online gender-based violence, the case study needs to resonate with the participants, which requires knowing where they are coming from and what their concerns are [Note: There is a section here about Getting to Know Your Participants.]

The Sample Case Study below would be useful in articulating the case study that you will share in this session. It outlines the Initial Presentation and the Escalation of the example to be deconstructed.

If you want to to create your own case study:

- flesh out the survivor, where they are coming from, their contexts

- be clear about where the incident happened first and how it escalated

- think about the impact of the incident: offline / online; on the individual, their community / family / friends; on their well-being, digital security, physical security

- try to describe the perpetrator/s´ actions but not their motivations

Additional resources

Sample case study: Selena's case

Initial presentation

Selena is in her final year of college. She attends college in Manila, Philippines, but she heads back to her province in Angeles every chance she gets to visit her parents and her younger siblings. In order to augment her limited funds for her studies, she is a part-time barista at a local coffee shop.

On one trip home, she finds her parents very upset. They accuse her of abusing her freedom in Manila and using her looks to meet foreign men. They slut-shame her, and threaten to cut off their support. They demand that she stop dating foreign men online and causing them problems.

Selena does not use any kind of dating app – she's too busy with school and work. And she already has a boyfriend.

After hours of her parents shouting at her, she finally gets a picture of what happened:

The day before, Heinz from Germany had knocked on her parents' door, demanding to see Selena. He brought with him copies of conversations that he has had with Selena, and the pictures that she has shared with him. Those conversations happened both on the dating app chat and on WhatsApp. He implied that he and Selena have engaged in cybersex. Apparently, he had sent Selena money so she could start applying for a German visa in order to visit him. When she did not get a visa, he had then sent her money to purchase a ticket so they could meet up in Bangkok, where they could be together without her conservative parents watching their every move. She did not show up. Heinz had tried getting in touch with her but she was unresponsive. So he felt he had no choice but to pay her parents a visit. They refused to let him in and threatened to call the authorities if he kept on insisting on seeing Selena.

Heinz had left, angry.

Sounds like a con gone wrong.

Problem: Selena is not aware of any of this. She has never talked to any Heinz. She has not received any money from him. She was not in a long-distance relationship with anyone.

It looks like Selena's pictures and identity were used to "catfish" Heinz.

(Catfishing is when someone takes screen-grabs of someone's photos online and creates accounts in their name in order to con other people. Sometimes, the real name of a person is attached to the fake account, but there have been cases where the photos are attached to fake names.)

Escalation

In response to the incident, Selena had removed all her photos from all her social media accounts, and had sent a message to the dating app and WhatsApp that the account with her pictures was a fake one that some people had used to swindle a German user.

She and her family have not heard back from Heinz. He seems to have left Angeles after her parents turned him away.

One day, at school, a few of her male classmates start heckling her, calling her a slut and a swindler, saying that it's a shame that a pretty girl like her would use her looks that way. One of Selena's friends show her a Facebook page called "Selena is a Slut Swindler". On that page, Heinz recounts what "Selena" had done to him – with screen grabs of their conversations, her pictures, and audio recordings of their cybersex sessions.

The page has trended, and has received a lot of likes and followers.

What can Selena do?

Sample case study: Dewi's case

Initial presentation

Dewi is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. She is a 30-something trans woman, working as a call centre agent for a large multi-national online retail company. With two of her closest friends, Citra and Indah, she has just recently started a small organisation to promote SOGIE equality in Indonesia.

Since they started the organisation, the three of them have been invited to local events around LGBTQI+ rights and have attended demonstrations to support their advocacy. She has been captured in the local news speaking out against toxic masculinity and religious fundamentalism.

One morning, as Dewa was getting ready to go to work, she receives a message on her Facebook Messenger. It´s from an account called, Mus: ¨You made me so happy last night. Do you want to make me happy again tonight?¨ She dismisses it as a wrongly-sent message, so she responds with: ¨I think this is not for me. Wrong send.¨

To which Mus replies, ¨It is meant for you, Ms. Dewi. I saw your pictures and I want to see you in person. So you can make me happy again.¨

Scared that Mus knows her name, she just messages back and says, ¨I don´t know you, please stop.¨ She then blocks Mus.

Then more messages keep showing up from different users on her FB Messenger. The messages get progressively ruder and more explicit. She is also getting more friend requests on Facebook. She opts to block those users and tries to ignore them.

She keeps Citra and Indah updated on what is happening and her two friends are getting worried for Dewi.

To try to get to a reason as to why Dewi was being harassed, Citra Googles Dewi´s name. What they find are images in which Dewi´s face is edited on to naked transwomen´s bodies. The images are all labeled with Dewi´s name, and posted on DIY pornography sites.

Immediately, the three of them write to where the images are posted to request for the take down of the photos and of Dewi´s name on them. They all hoped that that was the end of that and the harassment would stop.

Escalation

One day, Dewi´s supervisor calls her in for a meeting. Then the supervisor shows her Twitter messages addressed to their company with a copy of the doctored images with the caption: Is this what your employees look like? What kind of morals does your company have? Fire HIM!¨

According to her supervisor, their company´s Twitter account was bombarded with the same messages from multiple accounts.

What can Dewi do?

Story circle on online GBV [deepening activity]

This activity allows participants to reflect upon and share experiences of online GBV.

About this learning activity

This activity allows participants to reflect upon and share experiences of online GBV.

A safe space is the main prerequisite for this activity, and some quiet time for the participants to reflect.

This activity happens in two stages:

- Reflection Time, when each participant is given time to articulate and write down their story by answering a series of guide questions.

- Story Circle, where all the participants share their stories with each other.

It is important to note here that this Story Circle is not for the purposes of therapy. Being able to tell your story, even anonymised, has some therapeutic effects, but it should be made clear that this is not the purpose of the Story Circle. If you are dealing with a group that you know has experienced online GBV, especially if there are people in the group who have very recent experiences, you can either make sure that there is someone in the facilitating team who can provide therapy, or skip this learning activity, if you don't think you can handle the participants being re-traumatised.

Learning objectives this activity responds to

- An understanding of the forms of online GBV and its impacts on the survivors and their communities.

- An understanding of the continuum of violence between the offline and the online spheres, and the power structures that allow it.

Who is this activity for?

This activity can be carried out with participants with different levels of understanding and experience of online GBV.

It is important to know before doing this activity if there are participants whose experience of online GBV is current or fresh, as this activity might be a cause for stress for them. Knowing who your participants are, and also knowing what you as a trainer / facilitator can handle is important before considering this activity.

It is equally important for you, as a trainer / facilitator, to be honest about what you can and cannot hold. This activity is NOT recommended for situations where:

- you have not established trust between and among your participants

- you have not had the time to get to know your participants prior to the workshop

- you do not have any experience in handling difficult conversations

Based on the experience of story circle facilitators, it is ideal to have two facilitators for this activity.

Time required

Assuming that each participant will need about five minutes to tell their stories, and about 30 minutes will be needed to collectively reflect, plus some leeway to give instructions, then with a standard workshop size of 12, you will need a minimum of 100 minutes for this activity.

This suggested time for this activity does not include well-being activities that might be needed to address re-traumatisation of participants, or to take a break when needed. Ideally, for standard group size, holding this activity for half a day (4 hours, including breaks) would be sufficient to include well-being breaks and activities.

Resources needed for this activity

- Guide questions written down

- Space for people to reflect

- A big circle in the middle of the room for the participants to share.

Mechanics

This activity has two stages:

- Reflection Time, when each participant is given time to articulate and write down their story by answering a series of guide questions.

- Story Circle, where all the participants share their stories with each other.

During the Reflection Time stage, the participants are given 30 minutes to reflect upon a real-life example of online GBV. They can choose to tell their own experience or someone else's. Even if they are telling their own story, everyone is encouraged to anonymise their story. They should tell one story each.

In order to facilitate reflection, the participants may use the following guide questions to write down their story:

- Who is the survivor? Who was/were the aggressor/s? Who else is involved in the story?

- What happened? Where did the story happen? What kind of violence was committed?

- What was the impact of the violence? How did the survivor react? What did they fear the most? Did the situation escalate or worsen? How?

- What kind of support did the survivor get? Who able to provide support to the survivor?

- What actions did the survivor and their supporters take? How was the case resolved?

- How is the survivor doing now? How do they feel now about what had happened? What lessons have they learned from it?

- What role did technology play in this story? How did it affect the impact of the violence? How did it help in addressing the violence?

Facilitation Note: These are guide questions, and participants don't need to answer all of them. They are just there to help them articulate their stories.

Anonymising stories

Participants are encouraged to anonymise their stories, even if the story is theirs:

- Give the survivor a pseudonym that's not close to their name.

- Make the location of the survivor more general. If there are contextual issues that would make it possible to identify the survivor based on where they are from, then give the location a bigger reach. It's one thing to say that the survivor is from Petaling Jaya in Malaysia, and another to say they are in Kuala Lumpur or even Malaysia.

- Give vague details about the survivor (keep to general markers: gender, sexuality, country, religion, race, social class) but not about their experience of online GBV (the platforms and spaces where the online GBV happened, what they experienced, how it escalated, the impact on them).

Once everyone has written down their stories, gather the participants in a circle.

Lay down the rules for this story circle. It would be good to also have these written down where everyone can see it and reiterate this message.

- What is said in the story circle does not leave the story circle without the express permission of everyone in the circle.

- No one in the circle is allowed to invalidate the experiences being shared. The severity of the violence experienced is not a competition. Don't ask about graphic details of the story.

- Listeners can ask clarification questions but not questions that are invasive. Don't ask “why” questions, ask instead “how” or “what” questions.