Risk assessment

Introduce participants to the concepts that underlie risk assessment, and how to apply risk assessment frameworks to their personal and/or organizational security. We **highly recommended** that you choose a Learning Path to travel, as these include activities with different levels of depth that should help participants obtain more insight into the covered subjects.

- Learning objectives and learning activities

- Introduction to risk assessment [starter activity]

- Assessing communication practices [starter activity]

- Daily pie chart and risk [starter activity]

- The street at night [starter activity]

- Re-thinking risk and the five layers of risk [deepening activity]

- The data life cycle as a way to understand risk [deepening activity]

- Organising protests and risk assessment [tactical activity]

- Risk assessment basics [foundational material]

- Risk assessment in movement organising [foundational material]

Learning objectives and learning activities

This page will guide you through the Module's correct use and understanding. Following the Learning Paths, with activities of varying depth, should allow participants to obtain a better grasp of the studied subjects.

Learning objectives

By the end of this module, the participants will be able to:

- understand the concepts that underlie risk assessment

- apply risk assessment frameworks on their personal and / or organisational security

- come up with their own way of doing risk assessment that is relevant to their needs

Learning activities

Starter activities

- Introduction to risk assessment (presentation + discussion)

- Assessing communication practices

- Daily pie chart and risk

- The street at night

Deepening activities

- Re-thinking risk and the five layers of risk (presentation + discussion + group work)

- Data life-cycle as way to understand risk

Tactical activities

Foundational materials

Introduction to risk assessment [starter activity]

This activity is designed to introduce and exercise a framework for doing risk assessment.

Learning objectives

Learning objectives this activity responds to:

- Understanding the concepts that underlie risk assessment.

- Beginning to apply a risk assessment framework on their personal and/or organisational security.

Who is this activity for?

This activity is designed for participants who have basic or no experience of risk assessment. It is also designed for a workshop with participants from different organisations.

Time required

Realistically, this activity requires a day (eight hours, minimum) to do properly.

Resources

- Flip chart paper and markers

- Projector

- Laptops.

Mechanics

For this activity, create a scenario of an individual or group that the participants can practice doing a risk assessment on.

Depending on your participants, some options can be:

- A human rights group in a country that just passed a law to monitor NGOs

- A transwoman launching a website to support other transwomen

- A network of women’s rights advocates working on an issue that is considered taboo in their countries

- A group with a safe house for young transpeople

- A small LGBTIQ group under attack online

- A queer woman from a racial minority group posting their opinions online.

Break the participants down into groups. They can work on the same kind of organisation/group or work on different kinds of organisation.

Facilitation note: It is important here that the scenario resonates with the participants and that it is close to their experience.

Once everyone is in their groups, present the Basic risk assessment presentation.

Group work 1: Flesh out context and scenario

Before the groups can begin filling out the Risk assessment template, they should flesh out their chosen scenario.

For a group scenario:

- Create a profile for this organisation: location, size of the organisation, general mission of the organisation.

- Name their activities, or changes in their context, that put them at risk – this could be a new law, or they’re planning an activity that their detractors will want to interrupt. This could also be an internal shift that might present risks – e.g. a recent conflict within an organisation – or an external event that is causing significant internal stress among members of the organisation.

- Name who will be hostile to their actions, and who their allies are.

For an individual scenario:

- Create a profile for this individual: age, location, sexual orientation, how active they are on social media.

- Create the opinion they are being attacked for. Or describe the website they are creating that puts them at risk. Or the context situation that creates a vulnerable situation (e.g. being thrown out of their home, leaving an abusive relationship with someone in the same organisation or movement, etc.).

- Name who will be hostile to their actions, and who will support them.

Give each group an hour to do this.

Afterwards, have each group present their scenarios quickly.

Then present the Risk assessment template.

Some notes about the table:

- Threats should be specific – what is the threat (negative intention towards the individual group) and who is threatening them?

- Think about probability of a threat in three layers:

- Vulnerability – what are the processes, activities and behaviours of the individual or the group that increases the likelihood of the threat becoming real?

- Capacity of the people/person doing the threatening – who is making the threat and what can they do to enact it?

- Known incidents – has a similar threat been made with a similar scenario? If the answer is yes, then the probability increases.

- In thinking about impact, consider not just the individual impact, but the impact on a greater community.

- Assessing low/medium/high probability and impact will always be relative. But this is important to do in order to prioritise what risks to make mitigation plans for.

- Risk – this is a statement that contains the threat and the probability of it.

Group work 2: Risk assessment

Using the risk assessment template, each group analyses the risks in their scenario. The task here is to identify different risks, and analyse each one.

Facilitation note: Give each group a soft copy of the risk assessment template so they can document their discussions directly on it.

This group work will take at least two hours, with the trainer-facilitator consulting with each group throughout.

At the end of this, debrief with the groups by asking process questions rather than getting them to report back on their templates:

- What difficulties did your group have in assessing the risks?

- What were the main threats that you identified?

- What were the challenges in analysing probability?

Mitigation tactics input and discussion

Using the text for a presentation on mitigation tactics (see the Presentation section), present the main points and have a discussion with the participants.

Group work 3: Mitigation planning

Ask each group to identify a risk that is high probability and high impact. Then ask them to create a mitigation plan for this risk.

Guide questions

Preventive strategies

- What actions and capacities do you already have in order to avoid this threat?

- What actions will you take in order to prevent this threat from being realised? How will you change the processes in the network in order to prevent this threat from happening?

- Are there policies and procedures you need to create in order to do this?

- What skills will you need in order to avoid this threat?

Incident response

- What will you do when this threat is realised? What are the steps that you will take when this happens?

- How will you minimise the severity of the impact of this threat?

- What skills do you need in order to take the steps necessary to respond to this threat?

This group work will take about 45 minutes to an hour.

Afterwards, debrief by asking about the process and questions they have about the activities they have gone through.

To synthesise this learning activity, reiterate some lessons:

- Risk assessment is useful to come up with realistic strategies (preventive and responsive).

- Focus on the threats that have a high probability of being realised, and the ones with high impact.

- Risk assessment takes practice.

Presentation

There are three things to present in this activity:

- The basic risk assessment presentation

- The risk assessment template

- The mitigation tactics input (see text below).

Text for presentation on mitigation tactics

There are five general ways to mitigate risks:

Accept the risk and make contingency plans

Contingency planning is about imagining the risk and the worst case impact happening, and taking steps to deal with it.

Avoid the risk

Decrease your vulnerabilities. What skills will you need? What behavioural changes will you have to undertake to avoid the risk?

Control the risk

Decrease the severity of the impact. Focus on the impact and not the threat, and work towards minimising the impact. What skills will you need to address the impact?

Transfer the risk

Get an outside resource to assume the risk and its impact.

Monitor the risk for changes in probability and impact

This is generally for low-probability risks.

There are two ways to look at dealing with risks

Preventive strategies

- What actions and capacities do you already have in order to avoid this threat?

- What actions will you take in order to prevent this threat from being realised? How will you change the processes in the network in order to keep it from happening?

- Are there policies and procedures you need to create in order to do this?

- What skills will you need in order to prevent this threat from being realised?

Incident response

- What will you do when this threat is realised? What are the steps that you will take when this happens?

- How will you minimise the severity of the impact of this threat?

- What skills do you need in order to take the steps necessary to respond to this threat?

Adjustments for an organisational workshop

This activity can be used in a workshop context where the risk assessment is being done by an organisation, and the role of the trainer-facilitator is to guide the organisation through the process.

In order to do this, instead of fleshing out the scenario, have a discussion on the general threats that the organisation is facing. This could be a change in law or government that has implications on the organisation’s ability to continue its work. It could also be a specific incident when the people in the organisation felt that they were at risk (for example, a partner organisation discovering they are being surveilled, or the organisation itself being monitored). Follow that up with a discussion on what capacities the organisation already has – resources, connections, supporters and allies, and skills. Grounding a risk assessment activity by building common knowledge about the threats the organisation is facing and its capacities will be important for the rest of the process.

Break the participants up by team/unit as they go through the risk assessment template.

In this context, the mitigation planning is as important as the risk assessment template, so both areas will have to have equal time.

For an organisational context, this activity may take up to two days, depending on the size of the organisation and its operations.

Further reading (optional)

Assessing communication practices [starter activity]

This activity is designed to enable the participants to look at their communication practices (the topics that they communicate about, who they communicate with, their channels of communication) and assess where their risks are.

This activity is meant to be a diagnostic tool that can be used to prioritise training topics, and / or for the participants to use in assessing their communication practices.

Learning objectives

This addresses the understanding the concepts that underlie risk assessment.

Who is this activity for?

This is for participants that are beginners and intermediate.

Time required

Introduction to the activity: 15 mins

Individual time to assess: 15 mins

Group work: 30 mins

Plenum wrap-up: 30

Total: 1.5 hours

Resources

- Soft copies of the table. Or printed copies of this table

Mechanics

Ask the participants to fill in the table below.

| Topic of communication | Who do you communicate with about this topic | Is it sensitive?(Y/N) | Who will target you for this communication? | Communication channel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Y/N?) | ||||

| (Y/N?) | ||||

| (Y/N?) | ||||

| (Y/N?) | ||||

| (Y/N?) |

After each participant has done their table, ask them to share their results with each other in groups.

At the end of the group work, ask each group to discuss with the bigger group the following questions:

- What are the topics that you communicate about that are sensitive?

- Who are the groups / communities / individuals that will target you for your sensitive communications?

- What is the most used communication channel that you use? Do you think it is secure and private?

This activity can then be used to prioritise which communication channels to focus on for the rest of the workshop, or to present alternatives to less private communication platforms.

Daily pie chart and risk [starter activity]

The purpose of this activity is to get the participants to assess what their daily or weekly tasks are, and analyse how much of their working time are spent on each task. There are two parts to this exercise, the creation of the pie charts of their weekly or daily tasks, which ends in a small sharing session of their results. And the second part is figuring out where in their tasks they feel most at risk. It is important for the facilitator to not bring up the idea of risk until the second part of the activity.

This is a very basic way to do risk assessment that focuses on the tasks that they do and known risks that they commonly face at work. This activity should be done with a deeper risk assessment activity.

Learning objectives this activity responds to

- Apply risk assessment frameworks on their personal and / or organisational security

Who is this activity for?

- For participants who have not done any kind of risk assessment.

- This works for groups that do almost the same things throughout their work days.

- This would work as a starter exercise for an organisation that is going to do an organisational risk assessment.

Time required

1.5 hours, minimum

Resources

- Flip chart paper + markers

Mechanics

First part: Draw your pie chart

Each participant will be given a piece of paper where they would be asked to draw a circle, and divide the circle with their daily or weekly tasks in the organisation. The divisions should reflect the time they spend per task.

For the facilitator: Encourage the participants to be as specific as possible in listing down their tasks.

At the end of the drawing period, the group comes back together and discusses the following questions:

- Which tasks do each of them spend time in the most?

- Which tasks do the different participants share?

- Which of the tasks they are not spending that much time on do they wish they could have more time for? And why?

Basically, just have an open discussion to process their pie charts.

Second part: Identifying work risks

Ask the participants to reflect on their pie charts and answer the following questions:

- Of the tasks you do for your organisation, which do you feel has the most risk? What kind of risk? And why?

- How are you able to address the risks that you have in that task? Describe your strategies.

Then come back to the big group and have a discussion.

The street at night [starter activity]

This activity is about bringing out how we practise assessing risks in order to live and survive. In this activity, a dark street at night will be shown to the participants so that they answer the question, “What would you do in order to navigate this street alone safely?”

The exercise is meant to bring out ways that we automatically assess threats and mitigate them in this specific situation.

Learning objectives

By the end of this activity, the participants will:

- Begin to understand that risk assessment is not a foreign activity.

- Share some experiences about what they consider when looking at a risky situation.

Who is this activity for?

This activity can be done with participants who have no experience with risk assessment as well as those who have done risk assessments in the past.

Facilitator’s note: It is important for the trainer-facilitator to be familiar with the group, as this activity might activate past trauma about navigating streets at night among some participants.

Time required

45 minutes

Resources

- A projector where you can show a picture of a street a night

- A board or flip chart paper to write down responses

- Markers.

Mechanics

Introduce the exercise by showing a picture of a street at night. It is also good to remind the participants that there are no right or wrong answers.

There are some examples provided here, but you can also take your own picture that will fit into your context.

Photo: Yuma Yanagisawa, Small Station at night, on Flickr.

Photo: Andy Worthington, Deptford High Street at night, on Flickr

Give the participants time to reflect on answering the question: “How would you navigate this street alone at night?”

Intersectional note: You do not want to assume that everyone has the same physical capacities and abilities. This is why we are using navigate instead of walk.

Ask them to write down their responses for themselves .

This should take no more than five minutes. You do not want the participants to over-think their answers.

Then spend some time getting the participants to answer the question one at a time. At this point, as a facilitator-trainer, you are just writing down the participants’ answers on the board or the flip chart paper as they speak them out.

Once you see some trends in their responses – common responses as well as responses that are unique – begin asking the participants for the reason why they responded that way.

At this stage, we are somewhat reverse-engineering the process. We started with the how’s, now we are getting to the why’s. Here, we are looking for the threats – the causes of danger – that they have assumed in their answers to the how’s.

Note down the threats as well.

It is also a good idea to look at the photo again to see elements in it that could pose a threat, or that could be seen as opportunities to allow a person alone to navigate it more safely.

For example, in the first photo:

- Point out the fences and the low bushes. Are there good hiding places?

- Which side of the road would you walk on and why?

- Given that it is a road where a small station is, does that mean that the person walking on it will have someone to reach out to, in case something happens? If so, does that make it safer to walk on this street?

- What about walking along this road to be safe from cars passing by?

In the second photo:

- Which side of the street would you walk on, and why?

- Point out the two people on the street – does their presence make the street feel safer or not?

- The van further down the street – could it be a possible vulnerability or a source of assistance in case something happens?

If you are planning to do your own night-time street photo, consider having the following elements in it:

- You can have a picture where it is clear where the light source on the street is coming from, and an obvious dark side of the street.

- You can have a picture with elements on the street that add more risk to it. For example, places where someone else can hide from the person walking. Or a street with a lot of vehicular traffic.

After spending a bit of time on the why’s of the safety tactics and the threats, ask the participants the question: “What other things do you need to know about this street in order to make better decisions about how to navigate it safely?”

Allow them time to reflect on their responses.

Then gather their responses, and write them down on the board.

Synthesise the session. Highlight some key points:

- The key strategies – the why’s and how’s – that emerged from the discussion.

- The key information needed about a situation in order to better assess it that emerged from the session.

- Connect the activity to risk assessment in that during this activity, the participants looked into a situation (the dark street) and made some decisions about their safety and security in relation to that situation based on context, experience and insight. And this was done quickly.

- Being safe as you travel through a dark street at night is a common experience. And in that moment, we are able to assess the risk – How dangerous is this street? How fast can I run? Are there points on this street where I can ask for help, just in case? Am I walking alone? Are there spots where someone else could surprise me on this street? – and apply strategies and tactics to mitigate them. We mitigate risks instinctively – as a survival mechanism. Remembering this is important to do when you get into risk assessment.

- Knowing the potential risks in this specific situation has made it possible for each of us to come up with strategies and tactics to decrease our risks in the given situation.

Facilitator’s notes

- It is really important in the first part of this activity, during the participants’ reflection on how they would navigate the street safely by themselves, that they do not over-think. That is why five minutes is enough. What we want to highlight here is the importance of instinct and lived experience in assessing risks in a given situation.

- If you sense that a participant or all of them are being activated by having to respond to the experience of walking down a dark street, take a break. Give the participants a chance to breathe. Also allow participants to opt out of this activity.

- The point of this activity is to begin exploring assessing risks. It is not important here to match this activity to the standard formula, risk = threat x probability x impact / capacity. What is important is for the participants to be able to articulate the reasons why they decided on specific tactics for navigating the dark street at night.

- Reiterate that there are no right or wrong answers, only answers based on experience and reasoning.

- If you find, based on your knowledge of the participants, that doing an activity about navigating a street alone at night may activate their past trauma, you can alternatively choose to run this activity using a crowded street during the daytime, as that might not be as traumatic for participants. Or a crowded street at night, which can present different kinds of elements for thinking through risk. Here are some example photos that you can use:

Photo: Carl Campbell, El Chopo Saturday Market crowds, on Flickr.

Photo: Waychen C, Shilin Night Market, on Flickr.

Re-thinking risk and the five layers of risk [deepening activity]

At the moment, what we have is a some ideas about how to re-think risk. This has not been converted into a learning module.

Re-thinking risk and assessing risk

Realistically understanding risk

One of the challenges in risk assessment as we know it is the breadth of what we mean when we say ¨risk¨. To think about risk with a holistic approach even further widens what we mean by it (rightly so). The purpose of assessing risk is for an person to be able to come up with strategies and tactics to mitigate the risks that she faces, and to be able to make more informed decisions.

Often ¨Risk¨ is seen as anything that can go wrong in a situation without nuancing what risks one can focus on.

Another way of having a more nuanced assessment of risk is to think about it from three different angles:

- Known risks: Threats that have already been realised within the community. Cite examples. What are causes? What are its impacts?

- Emerging risks: Threats that have occurred but not within the community that the person belongs to. These could be threats that result from emerging threats from current political climates, technological developments, and / or changes within the broader activist communities.

- Unknowable risks: These are threats that are unforeesable and there is no way of knowing if and when it will emerge.

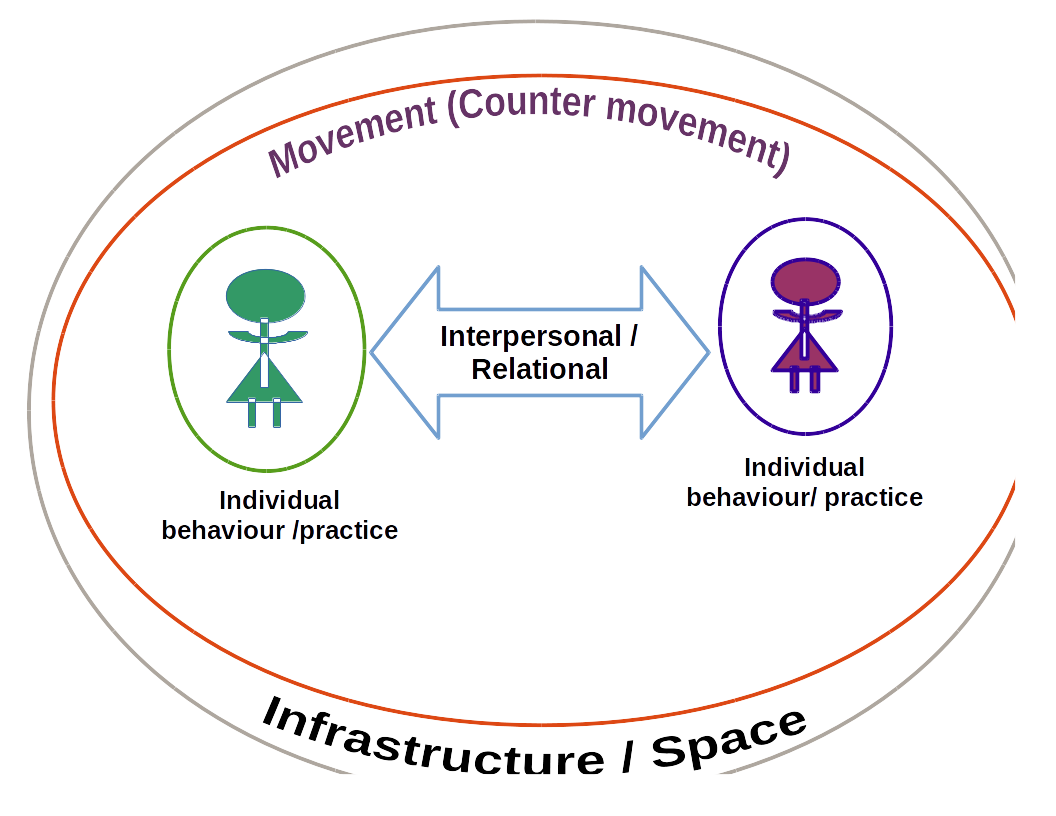

Another way to start thinking about risks is to consider these following layers:

Infrastructure / space layer

This layer is the space in which we move, communicate and interact. These are the offline and online spaces where we practice our activism. Wherever it is that we are located, there are parameters and those parameters may be sources of risks.

For example, the one known fact about the internet is that nothing in it can be permanently deleted. What kind of risks does this post for activists on the internet? How can this fact contribute to an escalation of threats?

Movement (counter-movement)

The next level is confronting the movements that we belong to, and who our opponents are. What are our movements´ capacities? And what are our opponents´? What are the risks that we face by default as part of feminist movements? Who are our allies? Who are our enemies? And what threats do they pose to us?

Thinking about risks in movement terms will also expand our understanding of the impacts of realised threats? What are the consequences, beyond the individual or organisational, of the gender-based harassment on the internet? How does it affect the way our movements are able to use the internet for our advocacies?

Relational / interpersonal layer

One of the assumptions that many activists do not confront is that the distrust and mistrust that exists within activist communities. It is important to build relationships of trust, yes. It is equally important to determine the levels of trust that exist between and among feminist activists.

Individual behaviour / practices

How do each of communicate? How do we get on the internet? What are the pre-existing realities that we individually exist in during our moments of interaction? What kind of equipment do we have access to? What kind of tools do we use? What skills do we have? The individual behaviour / practices answers these questions.

In order to understand risk deeper, it is important to interrogate these layers.

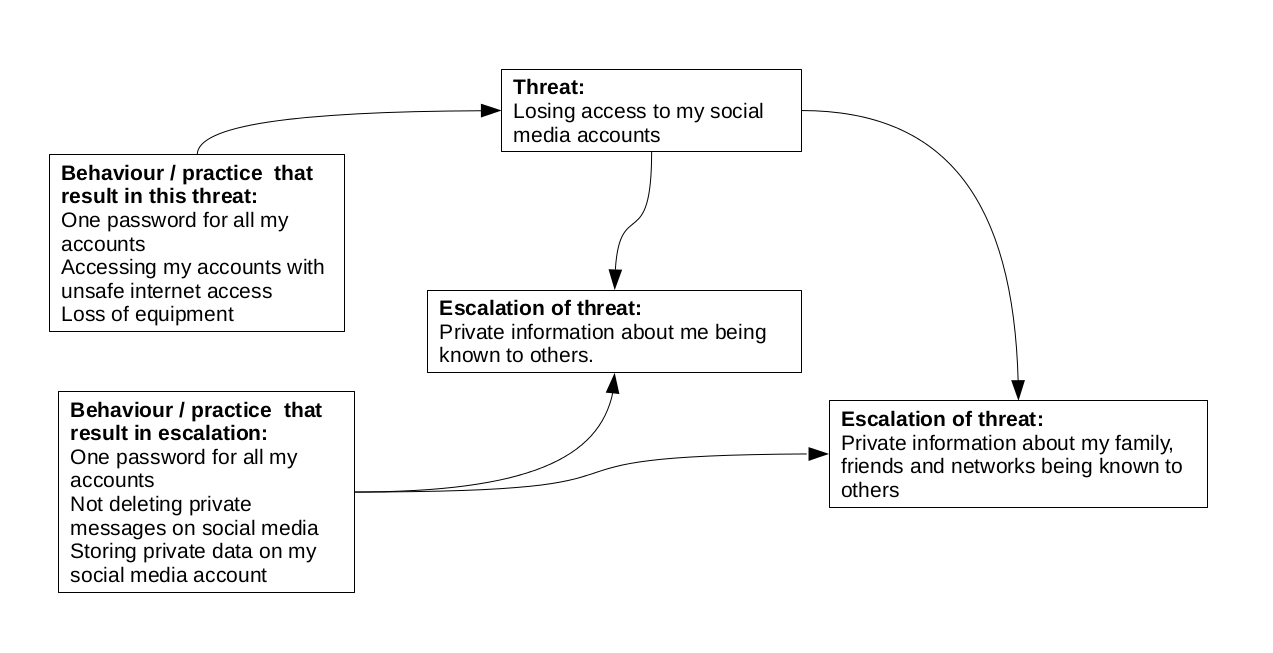

Continuum of behaviour / practice and threats

In this framework, we start with a known threat (or the ones that our participants will have had experience in) and interrogate the behaviour / practices that make the threat real and how the threat can escalate as well as the further behaviour / practices that allow the threat to escalate.

The second level for this framework would be identifying mitigation and responsive strategies at every point in the image.

The data life cycle as a way to understand risk [deepening activity]

Look at risk assessment from the perspective of the data life cycle. Activists, organisations and movements all deal with data – from gathering/creating/collecting data to publishing information based on data.

Introduction and mechanics for a general workshop

This learning activity is about looking at risk assessment from the perspective of the data life cycle. Activists, organisations and movements all deal with data – from gathering/creating/collecting data to publishing information based on data.

There are two main approaches to the mechanics of this activity:

- The general workshop is for a general digital security workshop, where the participants come from different organisations and/or don’t belong to any organisations.

- The organisational workshop is meant for a specific group and its staff. The general context for this type of workshop is that different teams within an organisation come together to to do a risk assessment of their organisational data practice and processes.

The learning objectives and the general topics/themes covered in both approaches are the same, but the facilitation methodologies and techniques will need to be adjusted for two different kinds of workshop scenarios.

Learning objectives

Through this activity, the participants will be able to:

- Understand risk and security considerations in each phase of the data life cycle.

- Apply risk assessment frameworks to their personal and/or organisational security.

Who is this activity for?

This activity is meant to be for individual activists (in a general risk assessment or digital security workshop), or for a group (an organisation, network, collective) undergoing a risk assessment process. There are two mechanics and approaches for this activity, depending on whether it is a general workshop or a workshop for a specific group.

It can also be used as a diagnostic activity in order to prioritise which practices or tools to focus on for the rest of a digital security workshop.

Time required

This depends on the number of participants and the size of the group. In general, this activity takes a minimum of four hours.

Resources

- Flip chart paper

- Markers

- Projector to present the data life cycle and the guide questions and for participant share-backs, if needed.

Mechanics

(This is for a general risk assessment or digital security workshop, where activists from different contexts come together in a training. The learning objectives remain the same but some of the training and facilitation tactics would differ from a workshop for a more established group of people.)

Phase 1: What do you publish?

In this part of the activity, the participants are asked: What do you publish as part of your work as an activist?

The point here is to start with the most obvious part of the data life cycle – processed data that is shared as information. This could be research reports, articles, blog posts, guides, books, websites, social media posts, etc.

This could be done in plenary, popcorn style. This is when the facilitator posts a question and asks for short and brief answers from the participants – like corn popping in a pan!

Phase 2: Presentation of the data life cycle and security considerations

The presentation is aimed at reminding the participants about the data management cycle. The key points for the presentation can be found here (see cycle-basics-presentation.odp).

Phase 3: Reflection time about personal data life cycles

Group the participants according to what they publish. Ask them to choose a specific example of something that they have published (an article, a research report, a book, etc.), and ask them to form groups based on similar work.

Here, there will be time for each of them to track the data life cycle of that published output, and then time as a group to share their reflections.

Reflection time should be about 15 minutes. Then group discussion would take about 45 minutes.

The guide questions for individual reflection time will be the considerations in the presentation.

For the group work, each group member will share the data life cycle of their published work.

Phase 4: Share-back and security considerations

Instead of having each group report back, the trainer-facilitator asks each group questions that will surface what was discussed in the groups.

Here are some questions you may use to debrief on the reflection time and the group discussion:

- What are the data storage devices that were most common in the group? What were the ones that were the only one used?

- What were the differences and commonalities in access to the data storage in your group?

- What about data processing? What tools were used in your group?

- Did anyone in the group publish something that put them or someone they know at risk? What was it?

- Has anyone in the group thought about archiving and deletion practice before today? If so, what were the practices around this?

- Were there safety and security concerns at any part of your data life cycle? What are they?

Synthesise the activity

At the end of the group presentations and sharing, the trainer-facilitator can synthesise the activity by:

- Pointing to key points made.

- Asking participants for key insights from the activity.

- Asking participants about changes in their data management practice that they learned about during the activity.

Mechanics for an organisational workshop

This is for a workshop for an organisation and its staff.

Phase 1: What information does each unit/programme/team of the organisation share?

Based on the configuration and structure of the organisation, ask each unit or team for an example of one thing that they share – within the organisation or outside the organisation.

Some examples to encourage response:

- For communications units – what are the reports that you publish?

- For research teams – what is the research that you report on?

- For administration and/or finance teams – who gets to see your organisation’s payroll? How about financial reports?

- For human resources departments – what about staff evaluations?

Facilitation note: This question is much easier to answer for teams that have outward-looking objectives, for example, the communications unit, or a programme that publishes reports and research. For more inward-looking units, like finance and administration or human resources, the trainer-facilitator may need to spend time on examples of what information they share.

The goal in this phase is to get the different teams to acknowledge that they all share information – within the organisation or outside of it. This is important because each team should be able to identify one or two types of information that they share when they assess risk in their data management practice.

Phase 2: Presentation of the data life cycle and security considerations

The presentation is about reminding the participants about the data management cycle. The key points for the presentation can be found here (see file cycle-basics-presentation.odp).

Phase 3: Group work

Within teams, ask each group to identify one to two types of information that they share/publish.

In order to prioritise, encourage the teams to think about the information that they want to secure the most, or information that they share that is sensitive.

Then, for each type of shared or published information, ask the teams to backtrack and look at its data life cycle. Use the presentation below to ask key questions about the data management practice for each piece of published or shared data.

At the end of this process, each team should be able to share with the rest the results of their discussions.

In general, the group work will take about an hour.

Phase 4: Group presentations and reflecting about safety

Depending on the size of the organisation and the work that each unit has done, give them time to present the results of their discussion to their co-workers. Encourage each team to think about creative presentations and highlights of their discussions. They do not need to share everything.

Encourage the listeners to take notes about what is being shared with them, as there will be time to share comments and give feedback after each presentation.

Realistically, this will take about 10 minutes/group.

The role of the trainer-facilitator here, aside from timekeeping and managing feedback, is to also provide feedback to each presentation. This is the time to put on your security practitioner hat.

Some areas to consider asking about:

- If the data gathering process is supposed to be private, wouldn’t it be better to use more secure communications tools?

- Who has access to the storage device in theory and in reality? In the case of physical storage devices, where are they located in the office?

- Who gets to see the raw data?

As a trainer-facilitator, you can also use this opportunity to share some recommendations and suggestions to make the organisation’s data management practices safer.

Facilitator’s note: There is a resource called Alternative Tools in Networking and Communications in the FTX: Safety Reboot that you might want to have a look at to guide this activity.

Phase 5: Back to the groups: security improvements

After all of the teams have presented, they return to their teams for further discussion and reflection on how they can better secure their data management processes and data.

The goal here for each group is to plan ways to be safer in all of the phases of their data life cycle.

By the end of this discussion, each team should have some plans as to how to be more secure in their data practice.

Note: The assumption here is that the group has undergone some basic security training in order to do this. Alternatively, the trainer-facilitator can use Phase 4 as an opportunity to provide some suggestions for more secure alternative tools, options and processes for the group’s data management practice.

Guide questions for group discussion

- Of the types of data that you manage, which ones are public (everyone can know about them), private (only the organisation can know about them), confidential (only the team and specific groups within the organisation can know about them) – and how can your team ensure that these different types of data can be private and confidential?

- How can your team ensure that you are able to manage who has access to your data?

- What are the retention and deletion policies of the platforms that you use to store and process your data online?

- How can the team practise more secure communications, especially about the private and confidential data and information?

- What practices and processes should the team have in place in order to preserve the privacy and confidentiality of their data?

- What should change in your data management practice in order to make it more secure? Look at the results of the previous group work and see what can be improved.

- What roles should each team member have in order to manage these changes?

Phase 6: Final presentation of plans

Here, each team will be given time to present the ways that they will secure their data management practice.

This is an opportunity for the entire organisation to share strategies and tactics, and learn from each other.

Synthesising the activity

At the end of the group presentations and sharing, the trainer-facilitator can synthesise the activity by:

• Pointing to key points made.

• Asking participants for key insights from the activity.

• Agreeing on next steps to operationalise the plans.

Presentation

Another way to understand risks in increments is to look at an organisation’s data practice. Every organisation deals with data, and each unit within an organisation does as well.

Here, there are some security and safety considerations for each phase of the data life cycle.

Creating/gathering/collecting data

- What kind of data is being gathered?

- Who creates/gathers/collects data?

- Will it put people at risk? Who will be put at risk for this data being released?

- How public/private/confidential is the data gathering process?

- What tools are you using to ensure the safety of the data gathering process?

Data storage

- Where is the data stored?

- Who has access to the data storage?

- What are the practices/processes/tools you are using to ensure the security of the storage device?

- Cloud storage vs physical storage vs device storage.

Data processing

- Who processes the data?

- Will the analysis of the data put individuals or groups at risk?

- What tools are being used to analyse the data?

- Who has access to the data analysis process/system?

- In the processing of data, are secondary copies of the data being stored elsewhere?

Publishing/sharing information from the processed data

- Where is the information/knowledge being published?

- Will the publication of the information put people at risk?

- Who are the target audiences of the published information?

- Do you have control over how the information is being published?

Archiving

- Where are the data and processed information being archived?

- Is the raw data being archived or just the processed information?

- Who has access to the archive?

- What are the conditions of accessing the archive?

Deletion

- When is the data being purged?

- What are the conditions of deletion?

- How can we be sure that all copies are deleted?

Facilitator’s notes

- This activity is a good way to be able to know and assess the digital security contexts, practice and processes of participants. It is a good idea to focus on that aspect rather than expect this activity to yield strategies and tactics for their improved digital security.

- For an organisational workshop, you may want to pay attention to the human resources and administration teams/units. First, in many organisations, these are usually the staff members who have not had prior digital security workshop experience, so many of the themes and topics may be new to them. Second, because a lot of their work is internal, they may not see their units as “publishing” anything. However, in many organisations, these units hold and process a lot of sensitive data (staff information, staff salaries, board meeting notes, organisational banking details, etc.) – so it is important to point that out in the workshop.

- Pay attention to the physical storage devices as well. If there are file cabinets where printed copies of documents are stored, ask where those cabinets are located and who has physical access to them. Sometimes, there’s a tendency to focus too much on online storage practice, and they can miss out on making their physical storage tactics more secure.

Further reading (optional)

- FTX Safety Reboot: Alternative Tools in Networking and Communications

- FTX: Safety Reboot :Mobile Safety Module

- Electronic Frontier Foundation's Surveillance Self-Defense – while this is largely for a US-based audience, this guide has useful sections that explain surveillance concepts and the tools used to circumvent them.

- Front Line Defenders' Guide to Secure Group Chat and Conferencing Tools – a useful guide to various secure chat and conferencing services and tools that meet Front Line Defenders’ criteria for what makes an app or service secure.

- Mozilla Foundation's Privacy Not Included website – which looks at the different privacy and security policies and practices of different services, platforms and devices to see they if match Mozilla's Minimum Security Standards, which include encryption, security updates, and privacy policies.

Organising protests and risk assessment [tactical activity]

Guide a group of people who are planning a protest into reflecting about and addressing the risks and threats that they may face. This activity can be applied for protests that are offline or online as well as protests that have offline and online components.

Introduction

This activity is about guiding a group of people who are planning a protest into reflecting about and addressing the risks and threats that they may face. This activity can be applied for protests that are offline or online as well as protests that have offline and online components.

This is not a protest planning activity but rather a risk assessment activity for a protest. It is assumed that before this activity is held, the group has already done some initial planning for what the protest will be about and its main strategies, tactics and activities.

Learning objectives

Through this activity, participants will learn to:

- Understand the different risks that they face in carrying out protest activities.

- Create a plan to respond to the identified risks in order to carry out a more secure protest.

Who is activity for?

This activity is useful for a group of people (organisation, network, collective) who have agreed to plan a protest together.

The group should have had initial planning about their protest, so the main strategies, tactics and activities have been discussed and agreed upon prior to this activity.

Time required

This activity will take a minimum of four hours.

Resources

- A big wall where sticky notes and flip chart paper can be pinned. If there is not a well suitable for this purpose, there should be a space cleared on the floor where participants can do this work together.

- Markers.

- Sticky notes.

- Devices where discussions can be electronically documented. It is important to assign people in the group to document the discussions and make sure that if the documentation is shared, it is via secure channels.

Mechanics for a workshop for a group planning a shared protest

This activity has three main phases:

- Phase 1 is about looking at risk from the angle of organisers, supporters and adversaries as sources of threats (direct and indirect threats as well as confronting ways that the protest can fail). Phase 1 is broken down into three different exercises that are designed for the group to arrive at a shared understanding of the possible risks that their planned protest is facing.

- Phase 2 is about strategising ways to mitigate possible vulnerabilities and failures of the protest, and what roles organisers have in the mitigation plan.

- Phase 3 focuses on operationalising secure internal communications among the participants.

Phase 1: Assessing where risks can come from

This phase has a few levels of participation and interaction in order to assess where the risks for the protest may be coming from. To make the mechanics clearer, the different levels have been marked as “exercises”.

Prepare a sheet of flip chart paper for each of the following:

- Organisers of the protest: Groups and individuals involved in planning the protest. They also include allies.

- Supporters: Groups and individuals that you expect to take part or participate in the protest actions.

- Adversaries of the protest: Groups and individuals who will be negatively affected by this protest as well as those that support them.

- Activities of the protest: The planned actions for the protest and where those actions are happening. Activities can be both online activities and offline activities.

Exercise 1: Naming the who and what of the protest

Give the participants time and space to fill in each of these sheets of flip chart paper with sticky notes with their responses. Alternatively, they can also just write directly on the flip chart paper.

Facilitation note: To do this in a more organised way, especially if the group is made up of more than seven people, break the participants into four groups. Each group will work on one sheet of flip chart paper first. One can start with “Organisers of the protest”, and another group can start with “Supporters of the protest”, and so on. Give them time to fill in their answers for their sheet of flip chart paper, then ask them to move to the next sheet until all groups have had time with each one. This is usually called the World Cafe methodology.

Exercise 2: Unpacking organisers, supporters and adversaries

After all the sheets of flip chart paper are filled with answers, get the participants to break out into two groups:

- Group 1 will take the flip chart paper for the organisers and supporters

- Group 2 will take the flip chart paper for the adversaries

The flip chart paper on Activities will be left in the common area for everyone’s reference.

Each group will have their own set of guide questions to start unpacking where the risks are in their focus areas.

For organisers and supporters, the guide questions are:

- Who among the organisers is currently facing threats? What are they? How can that impact the protest?

- Are there internal conflicts among the organisers? Tensions that we should be aware of? What might the potential impact be to the organising?

- Among the supporters that we expect, who among them have the potential to receive a lot of backlash?

- What are the threats of backlash that can be anticipated? Have there been similar protests that received backlash before? What was it?

- Where would the backlash or attacks happen? Do you know which social media spaces are especially targetted by adversaries? What might the impact of the backlash be on offline realities, during or after the protest?

For adversaries, the guide questions are:

- Who among this list of adversaries will be most active against the protest?

- Where do they congregate? Where do they congregate offline and online?

- Who are the leaders or influencers among the adversaries?

- What capacities do they have?

- What is it that they can do against the protest and those involved?

- How can the adversaries affect the planning of the protest?

- How can they disrupt the planned activities during the protest?

- What might post-protest backlash look like? How might adversaries try to disrupt the message of the protest through backlash? Who would they target? Where would this take place, and what is the role of social media in this?

Facilitation note: Most protests these days will have online and offline components. The questions above are applicable to both online and offline scenarios, protests and contexts. But, if you observe that the participants are focusing too much on offline contexts, then perhaps prompt them with questions about the online contexts of their organisers, supporters, and adversaries. If they are tending to focus on the online factors, then prompt them with questions about offline contexts. Prompt them on how the online activities or events can impact on offline activities or events, and vice versa.

The group discussion should take about 45 minutes to one hour.

At the end of the group discussion, each group will share back their discussion results. For the share-back, each group should focus on the following questions:

For the organisers/supporters group:

- Who among the organisers/supporters are currently facing threats? What threats are they facing?

- What kind of backlash are you expecting the organisers and supporters to face for participating in the protest?

- Were there internal conflicts or tensions that might pose a risk to the protest, and what might those be?

For the group that worked on adversaries:

- Who among the adversaries will potentially take action to disrupt the protest?

- What kind of disruptions do you expect from them?

- How does this look different for different stages of the protest: planning, during and post?

It is also a good idea to ask the groups to be as specific in their share-backs as they can be.

Exercise 3: Reflecting on possible failure

This exercise is about surfacing some of the possible ways that the protest can fail.

After this, all the participants will be given some time to reflect on this question: What do you NOT want to happen in this protest?

To further unpack this big question, you might want to raise these questions to prompt the group:

- Think about your organisers and supporters – what possible negative effects can this protest have on them?

- If the protest is happening offline and online, then how can your adversaries disrupt the protest in both spaces?

- Think about the spaces of your protest activities – what do you not want to happen to them?

- Think about your protest activities – what can cause them to fail?

Ask them to reflect on the discussions they’ve had and the share-backs they’ve listened to. Ask them to write down their answers on separate sticky notes and then have them post them up on the wall after a few minutes of reflection.

Cluster the responses to come up with general themes to discuss further.

Phase 2: Planning mitigation strategies and tactics

Exercise 1: Group work to mitigate possible vulnerabilities and failure

Based on the clusters from Exercise 3 of Phase 1, divide the participants into groups.

Each group will discuss the following questions:

- What can you do to prevent this negative outcome?

- What strategies, what approaches, what safety protocols will be required to avoid it?

- Are there different strategies for the planning stage, during the protest itself, and after?

- What will you do if this potential negative outcome becomes real? What steps will you take?

- Who should lead these strategies?

By the end of the discussion, each group should have a list of approaches and strategies as well as security protocols (rules) in relation to the negative outcome. These should be listed down on flip chart paper and/or documented electronically. Organise these according to the different stages of the protest: before, during and after. Each group will present their lists to the rest for discussion.

The role here of the trainer-facilitator is to provide feedback on the approaches and strategies, suggest improvements (if needed), and find common strategies among the groups.

Exercise 2: Discussion about roles

In the big group, have a discussion on the roles necessary to mitigate negative outcomes, adhere to security protocols, and manage secure communications – before, during and after protest activities. It would be important for the group to finalise these roles and who will fill them.

Phase 3: Communicating securely

Here, the trainer-facilitator can present options for secure communications for the group as they carry out the protest.

Then, the group can spend time installing and making sure that they are able to communicate with each other through the chosen channel.

To help you plan this, read Alternative Tools for Networking and Communications and the Mobile Safety module.

Security note: One of the ways that you can exercise these tools is to make sure that the people who are documenting are able to share copies of their notes and documentation via secure communication channels.

Adjustments for a general workshop

In general, risk assessment activities are more effective when they are done with groups that have common goals, contexts and risk scenarios (i.e. organisational risk assessment interventions, or risk assessment for a network of organisations). Therefore, this activity was designed for a group of participants who are already planning to carry out a protest together and have done some initial planning about their shared protest. But the activity can be adjusted for a more general digital security scenario of individuals from different contexts who are thinking about organising their own protests with their groups.

In order to adjust this activity for more general use, having a sample protest will be a good way to get the participants to practice this activity, and learn lessons that they can bring back to their groups/networks/collectives so that they can assess the risk of their actual protests.

Some guidelines about creating a sample protest:

- Locate the protest in reality: It is important to locate the protest in a real context, because then the sample protest will have the boundaries and parameters of an actual protest, and the participants will be able to be more specific in their analysis and their strategies.

If all the participants are from the same country, then locate the protest in that country. If they are from different countries, then have a regional protest. - Design a sample protest for an issue that resonates with the participants: This way, the protest will be familiar to the participants even though it is an imaginary one. They would have organised and/or participated in one in the past.

- State the protest demands or objectives: Make them clearly related to the issue at hand, to help with the exercise.

- Design offline and online protest activities: Make sure that when you identify the protest activities, you have a combination of online and offline tactics. Be specific about these activities – where will they happen, when will they happen, how long will these activities last?

- Base it on an actual protest: If you know of a protest that can work for the participants in your workshop, then use that as the sample protest.

The key in creating a sample protest is to try to simulate as much as you can a real protest scenario. Again, risk assessment activities are most effective with specifics.

You will also need to find ways and adjust your timing so that the participants can learn and absorb the sample protest. You can share the sample protest details before the training, but don’t assume that everyone has had time to read before the workshop. You can present the sample protest at the start of the workshop and give the participants hand-outs so that each group will have the information available to them as they go through the phases and exercises of this activity.

Risk assessment basics [foundational material]

Introduction

We assess our risk all the time. This is how we survive. It is a process that is not unique to digital and/or information security.

When take a walk at night on a quiet street, we make decisions about which side of the street to walk on, how to behave, what to prepare, how to walk, based on our understanding of the situation: Is this street known for being a dangerous one? Is the community where this street is a dangerous one? Do I know anyone on this street who could come to my aid? Can I run fast, if something happens? Am I carrying anything of value that I can bargain with? Am I carrying anything that can put me in greater harm? Which part of this street can I walk on to avoid possible harm?

When our organisations plan a new project, we consider the ways in which it could fail. We make design decisions based on what we know of the context and the factors in it that would lead to the project not achieving its goals.

When we organise protests, we look at ways to keep the protest and those in it safe. We organise buddy systems. We make sure there is immediate legal support in case of arrests. We instruct those attending about how to behave to avoid being harassed by authorities. We strategise ways in which to conduct a protest peacefully in order to lessen the risk to those participating. We have people in the protest whose responsibility is to maintain its safety.

While assessing our own risks may be a practice that we do instinctively, risk assessment is a specific process we undergo – usually as a collective – in order to know how we can avoid threats and/or respond to those threats.

Risk assessment: Online and offline

Assessing our risks online is not as instinctive, for various reasons. Many of us do not understand how the internet works and where its threats and risks are – and these continue to evolve and grow. Some have the attitude of perceiving online activities, actions and behaviour as not being “real”, with less serious effects than what happens to us physically. At the other end of the spectrum, those that know of or have experienced incidents where a person’s “real” life was affected by their online activities (people being scammed on dating sites, people whose taboo internet interactions were made public, or activists being arrested for saying something against their government) tend to have a paranoid view of the internet.

The reality is that for many activists, the online/offline binary is false. The use of digital devices (mobile phones, laptops, tablets, computers, etc.) and internet-based services, apps and platforms (Google, Facebook, Viber, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc.) is commonplace in the work of many activists – in organising and in advocacy work. How we organise and do our work as activists has evolved as technology has advanced and developed – and will continue to do so. The internet and digital technologies are a critical part of our organising infrastructure. We use them in communicating, organising activities, building our community, and also as a site of our activities. In-person gatherings and advocacy events are often accompanied by online engagement, especially on social media and through hashtags. In recent protest movements, there is often a seamless flow between online and offline mobilising, organising and gatherings.

Instead of perceiving what happens on the internet as something separate from our physical realities, think of offline <-> online realities as interconnected and porous. We exist in both, most of the time, at the same time. What is happening in one affects how we are in the other one

This also means that the risks and threats move from online to offline and vice versa. For example, advanced state surveillance strategies against activists and their movements exploit un-secure use of technologies (i.e. clicking on unverified links, or downloading and opening unverified files) in order to be able to gather more information about activists and their groups and movements that may eventually lead to physical surveillance. Anyone who has experienced online gender-based violence (OGBV) knows the psycho-social effects of such attacks and harassment. There have also been cases where OGBV has escalated to affecting the physical security of those who have been targeted. Different forms of OGBV (stalking, doxxing, harassment) have been tactics used against feminist and queer activists in order to threaten them into silence and compliance.

Thinking about the porous online <-> offline nature of threats and risks can be overwhelming – where do we begin assessing and knowing what the threats are and where they are coming from, and strategising what to do about them?

What is risk assessment?

Risk assessment is the beginning of a process to become more resilient in responding to changing contexts and threats. The purpose of assessing risk is to be able to come up with strategies and tactics to mitigate the risks, and to be able to make more informed decisions.

In general terms, risk is the exposure to the possibility of harm, injury or loss.

In risk assessment, it is the capacity (or lack thereof) of an individual/organisation/collective to respond to the impact(s) of a realised threat, or the capacity of an individual/organisation/collective avoid a threat from being realised.

There is a known formula for risk assessment:

Risk = threat x probability x impact/capacity

Wherein:

- Threat is any negative action aimed towards a person/group.

- Direct threats are declared intention to cause harm.

- Indirect threats are those that happen as a result of a change in a situation.

- In defining threats, it is important to identify where the threat is coming from. Even better, who is the threat from.

- Probability is the likelihood of a threat becoming real.

- A related concept to probability is vulnerability. This can be about location, practice and behaviour of the individual/group that increase the opportunities for a threat to be realised.

- This is also about the capacity of the groups/individuals that are making the threat, especially in relation to the individual/group that is being threatened.

- To assess probability, ask if you have real examples of a threat happening to someone or a group that you know – and compare that situation with yours.

- Impact is what will happen when the threat is realised. The consequences of the threat.

- Impact can be on the individual, organisational, network or movement.

- The higher the degree and number of impacts of one threat, the greater the risk.

- Capacities are skills, strengths and resources a group has access to in order to either minimise the probability of the threat, or respond to the impact of the threat.

Case study - threats and mitigation

Case study: Deya

To illustrate this, let’s use the fictional but fairly common experience of Deya. Deya is a feminist activist who uses her Twitter account to call out those who promote rape culture. As a result of this, Deya has been been harassed and threatened online.

The threat she is most concerned with are the people that promise to find out where she lives and share that information on the internet to invite others to cause her physical harm. In this case, the impact is clear – physical harm towards Deya. There are other threats such as harassing her employers to fire her from her job, and to harass her known friends online.

To do risk assessment, Deya will have to go through these threats and analyse them to assess their probability and impact – in order to plan how she can mitigate her risks.

Threat 1: To find out where she lives and share that information online

Most of the threats come from accounts online – most of whom she does not know, and cannot verify if they are actual people or fake accounts. She recognises a handful of those participating in these online threats as known actors who often take part in attacking women online. Based on her knowledge of their previous attacks, she knows that personal details have sometimes been published online, and this has created a real sense of fear for her personal safety.

Is there are a way for her to prevent this from happening? How likely is it that her harassers and attackers will find out where she lives? She needs to figure out how likely it is that her address is either already available on the internet or can be made available by one of her attackers.

In order to assess this, Deya can begin by doing a search for herself and the information that is available about her online – to see if there are physical spaces that are associated with her, and if these will point to her actual physical location. If she discovers that her home address is available on the internet, is there something she can do about it? If she discovers that her address is currently searchable on the internet, then what can she do to avoid having it publicly available?

Deya can also assess how vulnerable and/or secure her home is. Does she live in a building with guards and protocols for non-tenant access? Does she live in an apartment that she has to secure on her own? Does she live alone? What are the vulnerabilities in her home?

Deya will also have to assess her own existing capacities and resources to protect herself. If her home address is made public on the internet, can she move locations? Who is available to offer her support during this time? Are there authorities that she can call on for protection?

Threat 2: To harass her employers to get Deya fired from her job

Deya works for a human rights NGO so there is no threat of her being fired from her job. But the organisation’s office address is publicly known in her city and available on their website.

For Deya, the threat of being fired from her job is low. But the publicly available information about her NGO may be a vulnerability to Deya and the staff’s physical security.

In this scenario, the organisation must do their own risk assessment as a result of the threats being faced by one of their staff.

What to do with risks? General mitigation tactics

Beyond identifying and analysing threats, probability, impact and capacities, risk assessment also deals with making a mitigation plan for all the risks identified and analysed.

There are five general ways to mitigate risks:

Accept the risk and make contingency plans

Avoid the risk

This means decreasing the probability of a threat happening. This may mean implementing security policies to keep the group more secure. This could also mean behavioural changes that will increase the chances of avoiding a specific risk.

Control the risk

Sometimes, a group may decide on focusing on the impact of a threat and not on the threat itself. Controlling the risk means decreasing the severity of the impact.

Transfer the risk

Get an outside resource to assume the risk and its impact.

Monitor the risk for changes in probability and impact

This is usually the mitigation tactic for low-level risks.

Case study: Deya

To use Deya’s example again, she has options about what to do with the risks she is facing based on her analysis of each threat, the probability of each threat happening, the impact of each threat, and her own existing capacities to handle the threat and/or the impacts of the threat.

In a scenario where Deya’s home address is already searchable on the internet, the risk will have to be accepted and Deya can focus on making contingency plans. These plans can range from improving the security of her home to moving homes. What is possible will depend on Deya’s existing realities and contexts.

The other option for Deya in this scenario is to ask where her address is publicly available to take down that content. But this is not a foolproof tactic. It will help her avoid the risk if none of her harassers have seen it. But if some have seen it and taken a screenshot of that information, then there is very little that Deya can do to stop the information from spreading.

In a scenario where Deya’s address is not publicly known and available on the internet, there is more breathing room to avoid the risk. What can Deya then do to prevent her home address from being discovered by her harassers? Here, she can take down posts that are geo-tagged that are close to her home, and stop posting live geo-tagged posts.

In both scenarios (about her address being publicly available or not), Deya can also take steps to control the risk by focusing on protecting her home.

Good risk mitigation strategies will involve thinking about preventive strategies and incident response – assessing what can be done in order to avoid a threat, and what can be done when the threat is realised.

Preventive strategies

• What capacities do you already have in order to prevent this threat from being realised?

• What actions will you take in order to prevent this threat from being realised? How will you change the processes in the network in order to prevent this threat from happening?

• Are there policies and procedures you need to create in order to do this?

• What skills will you need in order to prevent this threat?

Incident response

• What will you do when this threat is realised? What are the steps that you will take when this threat happens?

• How will you minimise the severity of the impact of this threat?

• What skills do you need in order to take the steps necessary to respond to this threat?

Reminders

Risk assessments are time-bound

They happen within a specific time period – usually when a new threat emerges (e.g. change in government, change in laws, changes in platform security policies, for example), a threat becomes known (e.g. online harassment of activists, reports about activists’ accounts being compromised), or there is a change within a collective (e.g. a new project, new leadership). It is important, therefore, that risk assessments be revisited, because risk changes as threats emerge and disappear, and as the ability of a group and individuals within that group to respond to and recover from the impact of a threat changes.

Risk assessment is not an exact science

Each person who is part of a group that is undergoing a risk assessment process comes from a perspective and a position that affects their ability to know the likelihood of a threat to be realised, as well as their own capacities to either avoid a threat or respond to the impact of it. The point of risk assessment is to collectively understand these different perspectives within the group, and have a shared understanding of the risks they face. Risk assessments are relative. Different groups of people may face the same risk and threats, but their ability to avoid those threats and/or their ability to respond to the consequences of the threats differ.

Risk assessment will not ensure 100% safety, but it can prepare a group for threats

As there is no such thing as 100% safety and security, risk assessments cannot promise to guarantee that. What they can do is to enable an individual or a group to assess the threats and risks that can potentially affect them.

Risk assessment is about being able to analyse risks that are known and are emerging, in order to figure out which risks are impossible to predict

There are different types of risks:

• Known risks: Threats that have already been realised within the community. What are their causes? What are their impacts?

• Emerging risks: Threats that have occurred but not within the community that the person belongs to. These could be threats that result from from current political climates, technological developments, and/or changes within the broader activist communities.

• Unknowable risks: These are threats that are unforeseeable and there is no way of knowing if and when they will emerge.

Risk assessments are important in planning

They allow an individual or group to look at what will cause them harm, the consequences of those harms, and their capacities to be able to mitigate the harms and their consequences. Undergoing a risk assessment process allows groups to make realistic decisions about the risks they are facing. It allows them to prepare for threats.

Risk assessment is way to manage anxiety and fear

It is a good process to go through to unpack what people in a group fear – to create a balance between paranoia and complete lack of fear (pronoia), so that, as a group, they can make decisions about which risks to plan for.

Risk assessment in movement organising [foundational material]

Overview

When thinking about risk assessment at the level of movement organising, it means expanding the scope of consideration to also include shared spaces, processes, resources or activities that are helmed collectively – formally or informally.

Movements are larger than an organisation, and made up of relationships of shared political commitment and action between different actors. Movement actors can be comprised of individuals, organisations, collectives, community members or groups, and bring different knowledge, skills, contexts and priorities into a movement. How movement actors organise themselves, figure out roles and areas of responsibilities and come to agreements are important dimensions of movement organising, where risk assessment can also play a part in surfacing potential points of stress.

Risk assessment from a movement perspective

It's often easier to identify movements from hindsight, as they grow organically through time and in response to concerns of specific contexts and moments. Sometimes, we think of movements as protests, since that is often the site where many movements are visible and grow. But not all movements end (or begin) in protest. For example, many LGBTIQ++ movements in places where visibility carries a high cost organise and take action in less visible ways, such as creating closed community spaces online, where individuals can convene, converse, provide support and strategise for different kinds of interventions.

A movement is made up of many different moments or stages, such as community outreach, building evidence, deepening understanding, consensus building, taking action, holding space for collective care, distribution of resources and so on.

Each of these moments or stages can be specific times in which collective risk assessment can be undertaken by those who are holding space or process. It might be useful to think about movement security as having the conditions in which the many stages or components of movement work can take place and thrive.

Layers of risk

One way to begin the process of risk assessment from the perspective of movements is to unpack the different layers that need consideration. There are three components that interplay with each other.

1. Relationships and protocols

2. Spaces and infrastructure

3. Data and information

The next sections describe what each layer is about, and some of the components within them, including questions for discussion that can help to unpack, analyse and understand the risks, towards coming up with a plan.

1. Relationships/protocols

At the heart of strong movements are strong relationships which are built on the basis of trust. This is particularly important as movements are less about form than about the strength and tenacity of their relationships at different levels.

Risk assessment can take place at the level of the individual, organisation or informal groups. When approached from a movement building perspective, it means paying attention to the relationships between those levels.